Posted by James Capobianco under

rarebooksComments Off on Bindings and Classification

It’s the night before the last day of class, and I have to say that it has gone fairly quickly. I’m sad to be without Silver’s commentary and insight after this class, but have the completion of my assignments to look forward to (which I just couldn’t seem to manage to finish while I have been here).

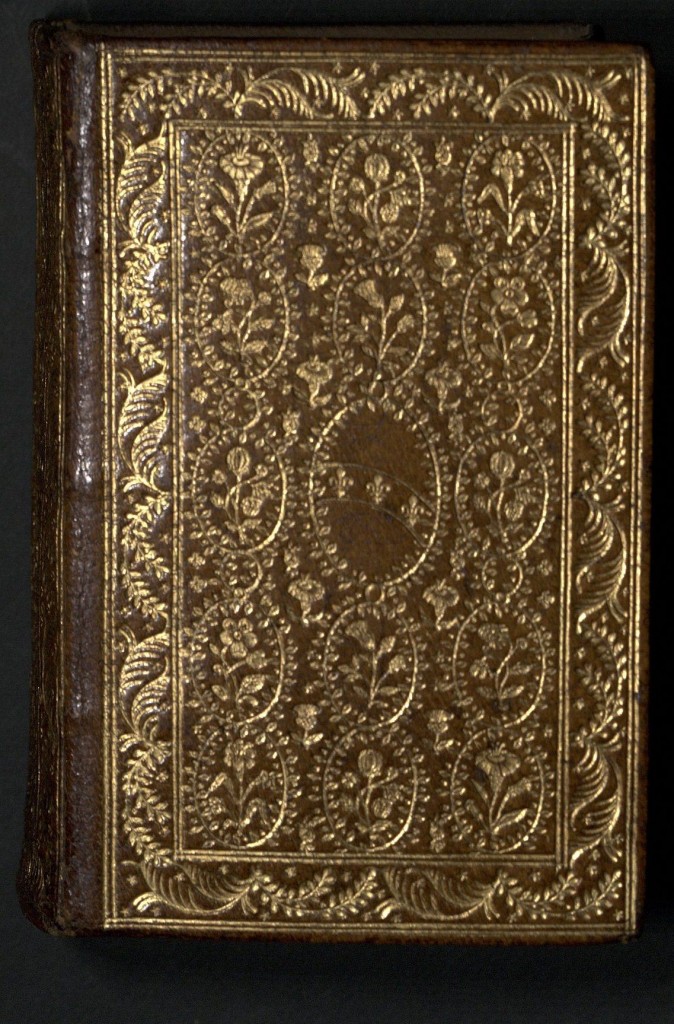

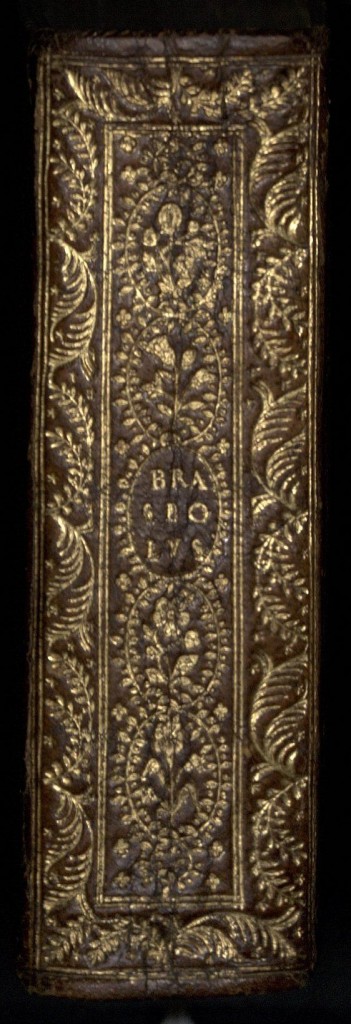

Today was a whirlwind of sources, including “Miscelaneous” subjects, like Art & Architecture, Music, and Children’s Books, and Book Arts and the physical aspects of books in general. It was a bit overwhelming. Outside of going over those sources, the highlight for me, which has encouraged my thinking most, was an aside Silver made while we were covering sources for bookbinding reference. He bemoaned the lack of opportunity people have for connecting with the physicality of books, both as private collectors and as a part of an institution. On the private side, many book stores and booksellers are taking their stock outside of public browsing and selling solely on the internet, leaving less opportunity to serendipitously encounter books. On the institutional side, collections move to off-site storage, and more attention to conservation has led to many volumes, especially older and more climate sensitive items, to be boxed, thus hiding their bindings, and making it much harder to answer reference questions about, for example, how many books of a certain peroid one has in contemporary bindings. Some of this information is available in an electronic catalog, but as has been my experience, those records are often either incomplete or non-existent (or not easily searchable).

I had thought of another aspect of this when he was talking and since, and that is placement of the books in rare book libraries, even in closed shelves, and the priority of cataloging. The idea of the most efficient way to shelf books has come up a few times in my short time at Houghton, and I had often thought that accessioning everything and shelving as things came in would be easier for space planning and retrieval. However, without like things being shelved together, it would be nearly impossible to answer a question about period bindings by walking to the stacks. There simply wouldn’t be any sections with enough like books to make that possible. Of course, the choice of call number system determines what characteristic of similarity is used for shelving. For Houghton “Author” class, for instance, it is the author’s origin place and time. Though most of the books might be from that time period and country, even first editions could be outside that country (not to mention later editions and translations). For instance, one of our final assignment questions for this class concerns More’s first edition of Utopia. Though classed *EC M8135U (as all of More’s Utopia editions will be in the Author system), it was published in Belgium, not in England. It might not therefore be a place to look for an English 16th century binding — and the Hollis record doesn’t set up any expectation of what binding we will find, contemporary or not. And the many other classification systems used for Houghton’s shelves (Old Widener, Typ, Accession Numbers, LC, etc.) will create different local similarities.

These may seem like trivial questions, but I actually think answering them refines the sense of the usability of the collection for staff and patrons. I fear with the rise of “folksonomies,” “tagging,” and keyword search supremacy in the general library world, we resist grappling with important questions of priority and classification that will in the long run not serve our patrons in the best way. Especially when small typographical and technical mistakes can lead to things falling through the cracks in an electronic environment, it pays for an item to be logically catalogued and traceable by some reproducible method (e.g. a systematic call number).