Motives and Justifications: A Critique of Fromkin’s Analysis of British Support for Zionism

ø

The issue of Israel and Palestine is extremely complex and a thorough understanding of its complexity requires a sound understanding of its historical roots. Many historians would agree that this conflict in its modern form dates back to the beginning of the 20th century. Fromkin’s account of this initial stage in the conflict is certainly one of the most influential ones and it has to be studied and critically examined prior to forming a judgment about this immensely complex issue. By citing imperialist and racist tendencies alongside essentially idealistic motivations like religion and romantic nationalism, Fromkin provides a very through account of all the ways in which Zionism found political support in Britain and elsewhere; however, he does not explain which of these causes were truly dominant and which of them were merely excuses. It seems to me that imperialism was the main reason why Britain like other imperialist countries wanted to assert its influence in the Middle East and other reasons that Fromkin mentions were merely instruments of gathering political support.

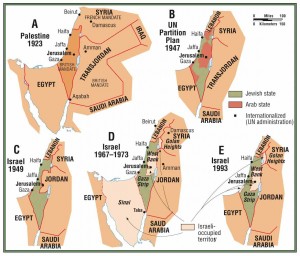

A. Palestine 1923 B. UN Partition Plan 1947 C. Israel 1949 D. Israel 1967-1973 – Occupied territories (annexation of the West Bank) E. Israel 1993 – Occupied territories

Imperialism was, of course, one of the main reasons why Britain was interested in helping the Zionist cause. Supporters of British imperialism argued that establishing a Jewish under the protectorate of the British would ensure British presence in and control of the region. One strong reason for this interest was Palestine’s geographic location as. “with the addition of Palestine and Mesopotamia, the Cape Town to Suez stretch could be linked up with the stretch of territory that ran through British-controlled Persia and the Indian Empire to Burma, Malaya, and the two great Dominions in the Pacific—Australia and New Zealand (Fromkin 281), Next, during WWI it became clear just how important oil is as a resource and the British leaders soon learned that the Middle East might be a region extremely rich in oil reserves (Fromkin 261).

The choice to support the creation of small nation states like a Jewish state and Palestine was seen as a more appealing option than to initiate outright occupation because it could prevent pan-Islamism from rising as an ideology in support of resistance to imperialism. British diplomat Sykes stated,” I want to see a permanent Anglo-French entente allied to the Jews, Arabs, and Armenians which will render pan-Islamism innocuous and protect India and Africa from the Turco-German combine, which I believe may well survive Hohenzollerns (Fromkin 290). Outright annexation was impractical because of the possibility of revolt led by the Turks (Fromkin 290). It was believed that the Turks could use their prominent position in the Islamic world to fuel a rebellious movement that would unite various Middle-Easter nations and ultimately push Britain away from the region.

A kind of idealistic, consistent nationalism was, according to Fromkin, one motive for British support for Zionism. The ideology of nationalism called for each nation to have its own country. Within this ideology most problems were explained by reference to the fact that a particular nation was subordinated to another one. Those who accepted nationalism truly argued that each nation has to have its own state, which would preclude imperialism. However, the question arose with respect to Jews because Jews of each Western European country were different than those from another country (Fromkin 272). Nationalists argued that Jews need to have their own state and they took the effort to come up with its geographic location. The Palestinian territories which were under Turkish rule were the choice. Based on agricultural research, nationalists argued that, “without displacing any of the 600,000 or so inhabitants of western Palestine, millions more could be settled on land made rich and fertile by scientific agriculture” (Fromkin 279). This meant that Palestinian territories could accommodate both the Jewish and the Palestinian nation state which was in accordance with the principles of nationalist ideology. One British dimplomat who espoused this view wrote, “most of us younger men who shared this hope were, like Mark Sykes, pro-Arab as well as pro-Zionist, and saw no essential incompatibility between the two ideals” (Fromkin 283).

Fromkin’s account of British support for Zionism also points to a paternalistic racist attitude of some British leaders towards the nations of the Middle East that was quite probably a remainder of traditional colonialist ideologies. The solution for the Middle East after WWI that the British proposed was to create a Palestinian and a Jewish state both under British protectorate. As Fromkin (263) points out, “Lloyd George, while employing the rhetoric of national liberation, proposed to give the Middle East better government than it could give itself”. In other words, the real meaning behind nationalistic romanticism that George advocated was a kind of alleged paternalistic benevolence based on a racist belief in superiority of Western peoples. The British Prime Minister who preceded Lloyd George, Asquith, once wrote about a justification for creating a Jewish and a Palestinian state as British protectorates that was penned by a British Cabinet Minister, Herbert Samuel, “it is a curious illustration of Dizzy’s [Disraeli’s] favourite maxim that ‘race is everything’ to find this almost lyrical outburst proceeding from the well-ordered and methodical brain of [Herbert Samuel]” (Fromkin 270). In other words, ancient racist excuses for colonial domination as a kind of benevolent paternalism were also used in this respect.

Finally, Fromkin argues that at least part of support for Zionism came from a peculiar brand of Protestantism that upheld the belief into the Promised Land as a powerful ideal. About Lloyd George, Fromkin (268) writes. “his Biblical knowledge and religion incited him to take the view that Palestine should not be divided and parceled after the war as it would be a sinful act”. This statement would suggest that George’s religion played an important role in the way he approached the issue of the Middle East. In addition, George was also connected to a Protestant line of thought that emphasized the need to return the Jews to Palestine in order to initiate the Second Coming of Christ by ultimately converting them into Christianity (Fromkin 268). Fromkin (269) writes that Zionism “became connected with” a mystical idea, never altogether lost in the nineteenth century, that Britain was to be the chosen instrument of God to bring back the Jews to the Holy Land”.

With regard to positive aspects of Fromkin’s analysis one first has to emphasize its thoroughness and scholarly quality. As has been demonstrated at least to an extent in this paper, Fromkin’s factual are always supported by an extraordinary amount of primary sources and data. For each of the motives that might have driven the British diplomacy in its choices regarding the Middle East, Fromkin finds ample evidence in addresses of politicians and other key figures, their letters and articles they wrote. For that reason, there is no doubt that the motives for support of Zionism outlined about were in fact publicly espoused by prominent British officials and other supporters of Zionism. Moreover, Fromkin’s account also has to be appreciated for the fact that it refrains from making strong factual or interpretative claims and indulging in speculation. Fromkin’s text adheres very tightly to historical facts and remains on the safe side when making interpretative claims.

As far as weaknesses of this positon are concerned, it should be stated that the interpretative side however modest it might be does not match the level of factual accuracy of the account. Namely, despite the fact that Fromkin has indeed proven that British officials publically espoused all of these motives, his contention that “many roads led to Zion” (Fromkin 275) meaning that British support for Zionism was motivated by all of these reasons simply does not follow. It seems naïve to believe that politicians are always sincere in their public statements and it often happens that they express false reasoning behind a certain action merely to get wider support. In this sense, it is worth remembering all the different rationales for the invasion of Iraq that the Bush Administration gave many of which later turned out to be completely false. It seems to me that the real motive behind British support for Zionism was its imperial ambition in the region. This is evident not just in the fact that the Middle East is rich in resources and has an important geographic but in the way in which the entire political maneuver was executed. Choosing to create a Jewish state in the Middle of a Muslim majority region and to refrain from direct occupation introduces an array of complications for organizing resistance. In other word, British support for Zionism was a tactical decision about how to create the best possible situation in which to exert influence over the Middle East.

In conclusion, Fromkin’s account of British support for Zionism is very useful because it shows all the ways in which a Zionist movement could get political support in Britain and elsewhere; however, it is not as powerful in ranking those motives for support and identifying a crucial one. Zionism was clearly supported by imperial interests as it could ensure British presence in a region of remarkable geopolitical importance and with rich oil reserves. It also got support from various religious groups who believed that Britain has a biblical duty to help to return the Jews to their Promised Land. Also, some nationalists supported a Jewish state because they firmly believed that partitioning the world in such a way that each nation gets its own nation state will resolve most of the world’s problem. While Fromkin provides ample evidence to show that all of these motives were publically stated by British officials, he is not so compelling when he says that all of them were equally important. It is quite clear that imperial ambitions were the true cause of British support for Zionism and all other justifications were merely a way of ensuring wider political support for that project.

Fromkin, David. A Peace to End All Peace: Creating the Modern Middle East, 1914-1922. New York: H. Holt, 1989. Print.