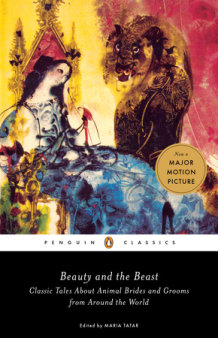

Below is what I wrote for Signature about the Beauty and the Beast story:

http://www.signature-reads.com/2017/03/the-primal-and-mythical-allure-of-beauty-and-the-beast/

Fairy tales are like riddles wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma, and that’s what accounts in part for our fierce repetition compulsion when it comes to stories like Sleeping Beauty, Cinderella, or The Frog King. It is always something of a challenge to figure out what makes a fairy tale tick and whir with cultural energy and why each one tends to carry some kind of emotional charge.

The anthropologists tell us that animals are good to think with, and in many ways we can imagine that stories about animal brides and animal grooms enabled our ancestors to address complicated issues turning not just on courtship but also on sexuality – in all its beastliness and tenderness. After all, sex stands at the point of intersection between the human and the animal kingdom, and the symbolic always helps us navigate the real. Some have speculated that Beauty and the Beast tales once served some kind of totemic purpose, helping humans to organize and understand their own social worlds. They also surely represented alterity in all its monstrous and terrifying incarnations, challenging humans to find some way of coexisting with lions, tigers, and bears, oh my, along with all the bugbears that haunt our imagination.

Our version of “Beauty and the Beast” derives from Mme de Beaumont’s 1756 story, published in a magazine with designs on the young, teaching them about character and good manners. In that French tale, Beauty not only outshines everyone in looks, she is also “good,” “kind,” “sweet,” and “sincere,” amassing a set of attributes that would be impossible for anyone, let alone most little girls, to replicate. Why does the classically attractive and instinctively generous Beauty settle by marrying a Beast who is grotesquely ugly and desperately needy? In Mme de Beaumont’s tale, Beauty discovers that she feels something more than friendship for the Beast and that she cannot live without him. Three “peaceful” months at the castle, full of “good plain talk,” along with the discovery that Beast is “kind” and has “good qualities,” arouse Beauty’s compassion, so much so that she can agree to marry him when he stops eating and nearly dies of starvation.

What is the social messaging in that story (which we have made our own through picture books and through the Disney film) and how does it differ from what we find in the long ago and far away of the fairy-tale universe? To begin with, we are drawn to Mme de Beaumont’s version of Beauty and the Beast precisely because it enshrines empathy as the greatest of virtues and as the pathway to true love – even if in the most hypocritical sort of way. Who knew that hotness is not at all a factor and that charity, generosity, and pity reign supreme when it comes to romantic alliances? We live in what has been called an age of empathy, with dozens of books on why empathy matters, on the neuroscience of empathy, on the empathy gap, and so on. And so it is no surprise that we instinctively recoil from stories like the Filipino Chonguita, in which an act of defiance or outrage – hurling an animal against the wall – disenchants the animal groom or animal bride. There we are in the arena of brute force and passion rather than compassion.

Yet stories like those, along with the Latin American The Condor and the Shepherdess (with its abducted heroine who has to put up with a dinner of carrion) or the Ghanaian Girl and the Hyena-Man (which ends with a clever ruse used to escape an arranged marriage), remind us that the most satisfying narratives are those that shock and startle us. Counterintuitive finales get us talking about the terms of the story – the cultural contradictions that are so artfully encapsulated in fairy tales and give them their staying power. That’s the self-reflexive genius of the fairy tale and of the mythic imagination, to give us stories about the power of talk (those long dinner conversations between Beauty and the Beast light the spark) and to leave us with something to talk about. In African cultures, a popular genre is the dilemma tale, a story that recounts an extreme situation and ends with a question. For example, a boy is given the choice of executing his cruel biological father or his kind adoptive father – and now you must decide which of the two he should slay. Fairy tales make us wonder and try to find solutions as we wander through their storied precincts.

Disney’s “Beauty and the Beast,” like the many other versions, gave us a vivid, visual grammar for thinking about abstractions: cruelty and compassion, surfaces and essences, hostility and hospitality, predators and victims. Like all fairy tales, it gives us the primal and the mythical, getting us talking in ways that headlines do their cultural work today. And they also lead us to keep hitting the refresh button, as we try to get the story right, even as we know that Beauty and the Beast will always be at odds with each other in an endless struggle to resolve their differences.

Dear Dr. Tatar, I enjoyed your post above on BEAUTY AND THE BEAST, as I do your many wonderful books on fairy tales. Regarding Disney’s Belle in both versions, I’ve always thought the best thing about her is is her intellectual curiosity, which makes her odd to her community. I think the reason she stays is that she sees all these books, which he grants her access to. Plus she tunes in to how the others in the castle feel about him, and knows there must be more to him.

My daughter’s English teacher, a strong feminist, has been weighing in on BATB since the movie came out. She says she could never get behind a tale in which the heroine has such an egregious case of Stockholm Syndrome!