When I last read “Middlemarch,” I was a high-school senior, without much knowledge of Victorian culture. But I feel sure that Dorothea’s words and thoughts, as she surveys the marital home in which she will live, made a deep impression on me. Last night, I read the chapter in which Dorothea sinks into silence and feels some disappointment that there will be “nothing for her to do in Lowick.” She almost hopes for “a larger share of the world’s misery” in the parish where she will live, because that means she will have something to do. “I have known so few ways of making my life good for anything.”

I could not help but think of Florence Nightingale’s “Cassandra,” an essay in which the woman who would take over the management of a British military hospital during the Crimean War and save countless lives describes herself as “shrieking aloud in her agony,” not because of her ineffectual prophecies, but because of an “accumulation of nervous energy, which has nothing to do during the day.” Nightingale was tormented by the thought that “the inability to exercise ‘passion, intellect, and moral activity’ would doom British women of privilege to madness.”

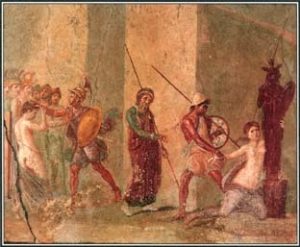

It is worth recalling that Cassandra, the daughter of the Trojan King Priam and Queen Hecuba, was wooed by Apollo, who tried to win her over by promising her the gift of prophecy. There are many versions of the story, and the one told by Hyginus in his Fabulae, reports that Cassandra spurned Apollo’s advances (he approaches her while she is sleeping), and the god retaliated by turning his gift to her into a curse (in some versions by spitting in her mouth).

It was genius of Florence Nightingale to recognize how closely aligned Cassandra’s lack of credibility aligned with the plight of Victorian women. Only a hundred pages now into Middlemarch, it becomes evident how Miss Brooke is never taken seriously and the target of constant condescension for her misguided aspirations to do some good in the world or to broaden her knowledge by trying to keep up with her husband’s broad reading. No surprise that the philanthropic efforts of women like Dorothea are mercilessly mocked by Charles Dickens through the figure of Mrs. Jellyby, with her “telescopic philanthropy” that is invested in charitable causes in Africa even as she neglects those in her domestic orbit.

“Middlemarch” captures the deep frustrations of privileged women with nothing to do, and George Eliot captured in fiction what Florence Nightingale described with such eloquence and passion in “Cassandra.” It’s fascinating to me that I grew up in a culture that saw heroism in Florence Nightingale and Clara Barton. Today, it’s old-fashioned to invoke their names and histories, but rediscovering them this past year left me in awe of what they accomplished in a world that was telling them to stay at home and have children.