Dear Readers,

Below are my annotated notes of a talk I gave at Berkman’s Truthiness in Digital Media Symposium a few weeks ago. I introduced the concept of Social Theorems, as a way of formulating the findings of the research that is happening the last few years in the study of Social Media. It is my impression that, while we publish a lot of papers, write a lot of blogs and the journalists report often on this work, we have troubles communicating clearly our findings. I believe that we need both to clarify our findings (thus the Social Theorems), and to repeat experiments so that we know we have enough evidence on what we really find. I am working on a longer version of this blog and your feedback is welcome!

Best,

P. Takis Metaxas

——————————————————————————————————

With the development of the Social Web and the availability of data that are produced by humans, Scientists and Mathematicians have gotten an interest in studying issues traditionally interesting mainly to Social Scientists.

What we have also discovered is that Society is very different than Nature.

What do I mean by that? Natural phenomena are amenable to understanding using the scientific method and mathematical tools because they can be reproduced consistently every time. In the so-called STEM disciplines, we discover natural laws and mathematical theorems and keep building on our understanding of Nature. We can create hypotheses, design experiments and study their results, with the expectation that, when we repeat the experiments, the results will be substantially the same.

But when it comes to Social phenomena, we are far less clear about what tools and methods to use. We certainly use the ones we have used in Science, but they do not seem to produce the same concrete understanding that we enjoy with Nature. Humans may not always behave in the same, predictable ways and thus our experiments may not be easily reproducible.

What have we learned so far about Social phenomena from studying the data we collect in the Social Web? Below are three Social Theorems I have encountered in the research areas I am studying. I call them “Social Theorems” because, unlike mathematical Theorems, they are not expected to apply consistently in every situation; they apply most of the time and when enough attention has been paid by enough people. Proving Social Theorems involves providing enough evidence of their validity, along with description of their exceptions (situations that they do not apply). It is also important ti have a theory, an explanation, of why they are true. Disproving them involves showing that a significant number of counter examples exists. It is not enough to have a single counter example to disprove a social theorem, as people are able to create one just for fun. One has to show that at least a significant minority of all cases related to a Social Theorem are counter-examples.

- SoThm 1. Re-tweets (unedited) about political issues indicate agreement, reveal communities of likely minded people.

- SoThm 2. Given enough time and people’s attention, lies have short questioned lives.

- SoThm 3. People with open minds and critical thinking abilities are better at figuring out truth than those without. (Technology can help in the process.)

So, what evidence do we have so far about the validity of these Social Theorems? Since this is simply a blog, I will try to outline the evidence with a couple of examples. I am currently working on a longer version of this blog, and your feedback is greatly appreciated.

Evidence for SoThm1.

There are a couple papers that present evidence that “Re-tweets (unedited) about political issues indicate agreement, reveal communities of likely minded people.” The first is the From Obscurity to Prominence in Minutes: Political Speech and Real-Time Search paper that I co-authored with Eni Mustafaraj and presented at the WebScience 2010 conference.

When we looked at the most active 200 Twitter users who were tweeting about the 2010 MA Special Senatorial election (those who sent at least 100 tweets in the week before the elections), we found that their re-tweets were revealing their political affiliations. First, we completely characterized them into liberals and conservatives based on their profiles and their tweets. Then we looked at how they were retweeting. In fact, 99% of the conservatives were only retweeting other conservatives’ messages and 96% of liberals those of other liberals’.

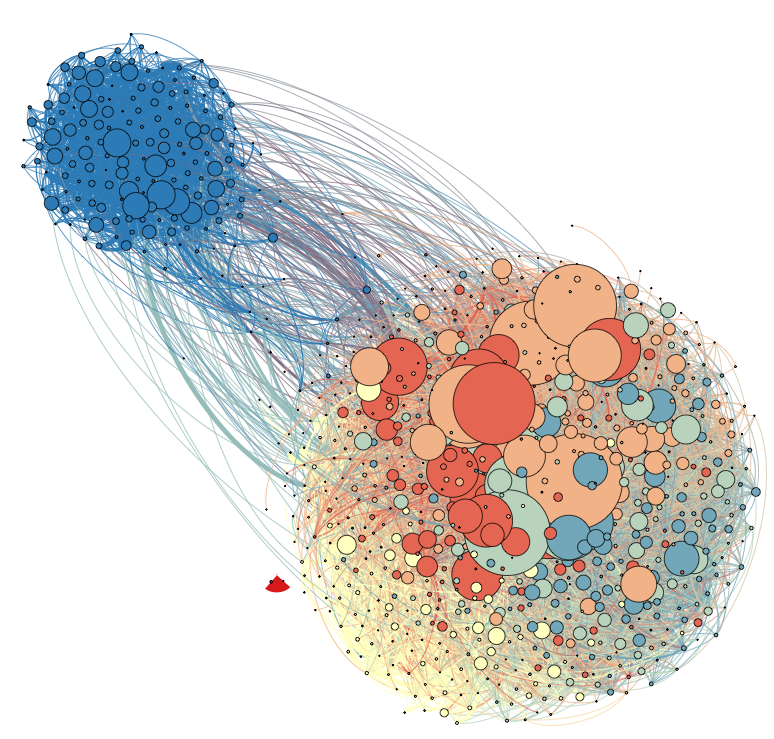

Then we looked at the retweeting patterns of the 1000 most active accounts (those sent at least 30 tweets in the week before the elections) and we discovered the graph below:

As you may have guessed, the liberals and conservatives are re-tweeting mostly the messages of their own folk. In addition, it makes sense: The act of re-tweeting has the effect of spreading a message to your own followers. If a liberal or conservative re-tweets (=repeats a message without modification), he/she wants this message to spread. In a politically charged climate, e.g., before some important elections, he/she will not be willing to spread a message that he disagrees with.

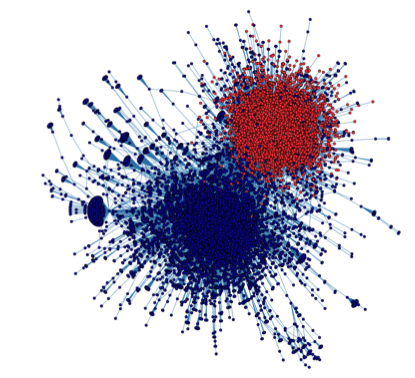

The second evidence comes from the paper “Political Polarization on Twitter” by Conover et. al. presented at the 2011 ICWSM conference. The retweeting pattern, shown below, indicates also a highly polarized environment.

In both cases, the pattern of user behavior is not applying 100% of the time, but it does apply most of the time. That is what makes this a Social Theorem.

Evidence for SoThm2.

The “Given enough time and people’s attention, lies have short questioned lives” Social Theorem describes a more interesting phenomenon because people tend to worry that lies somehow are much more powerful than truths. This worry stems mostly from our wish that no lie ever wins out, though we each know several lies that have survived. (For example, one could claim that there are several major religions in existence today that are propagating major lies.)

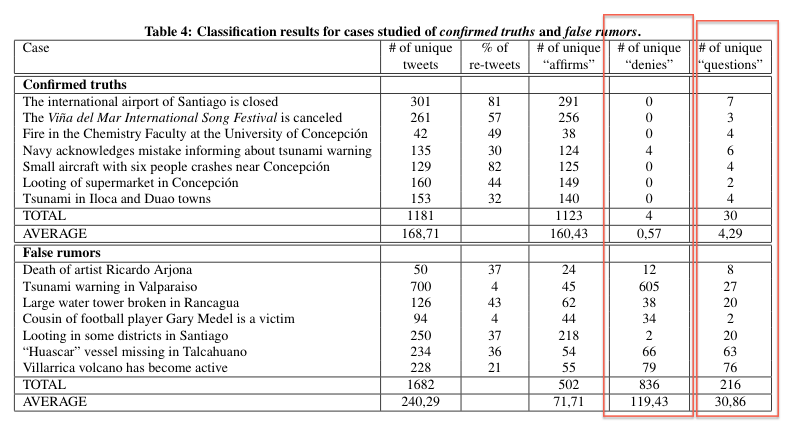

In our networked world, things are better, the evidence indicates. The next table comes from the “Twitter Under Crisis: Can we trust what we RT?” paper by Mendoza et. al., presented at the SOMA2010 Meeting. The authors examine some of the false and true rumors circulated after the Chilean earthquake in 2010. What they found is that rumors about confirmed truths had very few “denies” and were not questioned much during their propagation. On the other hand, those about confirmed false rumors were both questioned a lot and were denied much more often. Why does this make sense? Large crowds are not easily fooled as the research on crowd sourcing has indicated.

Again, these findings do not claim that no lies will ever propagate, but that they will be confronted, questioned, and denied by others as they propagate. By comparison, truths will have a very different experience in their propagation.

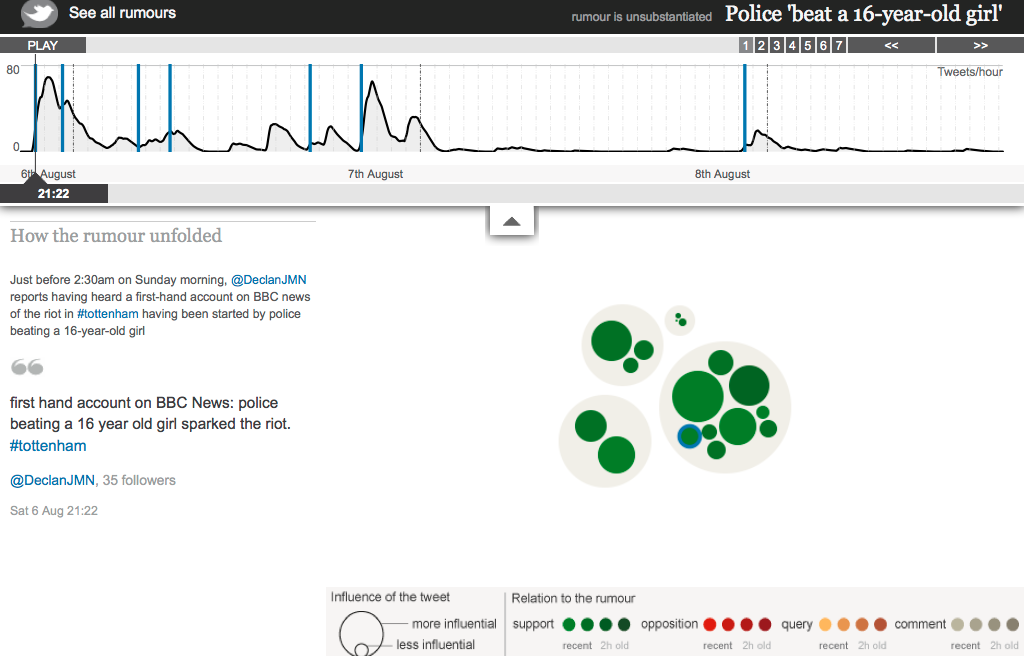

The next evidence comes from the London Riots in August 2011. At the time, members of the UK government accused Twitter of spreading rumors and suggested it should be restricted in crises like these. The team that collected and studied the rumor propagation on Twitter found that this was not the case: False rumors were again, short-lived and often questioned during the riots. In a great interactive tool, the Guardian shows in detail the propagation of 7 such false rumors. I am reproducing below an image of one of them, the interested reader should take a closer look at the Guardian link.

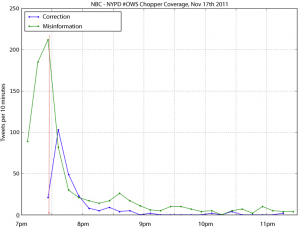

During the Truthiness symposium, another case was presented, one that supposedly shows the flip side of this social theorem: That “misinformation has longer life, further spread on Twitter than accompanying corrections”. I copy the graph that supposedly shows that, for reference.

Further, the above example may not be as bad as it looks initially. First, note that the graph shows that the false spreading had a short life, it did not last more than a few hours. Moreover, note that the false rumor’s spreading was curbed as soon as the correction came out (see the red vertical line just before 7:30PM). This indicates that the correction probably had a significant effect in curbing the false information, as it might have continue to spread at the same rate as it did before.

Evidence for SoThm3.

I must admit that “People with open minds and critical thinking abilities are better at figuring out truth than those without” is a Social Theorem that I would like to be correct, I believe it to be correct, but I am not sure on how exactly to measure it. It makes sense: After all our educational systems since the Enlightenment is based on it. But how exactly do you created controlled experiments to prove or disprove it?

Here, Dear Reader, I ask for your suggestions.

Thanks for your thoughtful theorems, Takis. I can appreciate your dilemma on #3, and I think the only way out of it is to reshape it somewhat. The minute you start getting in value-laden terms like “open mindness” you’ve set up yourself up for failure. Perhaps a more operational and measurable theorem might be something like “People will accept a new idea in direct relation to their degree of cognitive bias on the subject in general.” I’m not a social scientist, but I suspect there’s a way to measure a person’s cognitive bias on a particular topic. So you’re basically looking at where a person is along the spectrum from “closed” to “open” rather than one polar end. That seems easier to test to me.