What we need, and don’t yet have:

For independence on the Net and the Web, we need cars, pickup trucks, bikes and motorcycles. Not just shopping carts — which are what browsers have become.

Personal vehicles give us independence. They let us drive and shop all over the place, coming and going as we please. In different stores we use the shopping carts provided for us; but we haul home what we buy in our own vehicles. We also meet sellers in stores at a human level, person-to-person. We can talk.

Even if we don’t own the vehicle we drive, we experience independence. Whether we drive a Ford, a Volkswagen or a Toyota, that car or pickup is ours. It is an extension of ourselves. We know in our bones, as drivers, that this is my engine, my doors, my tires. No company is saying “my” for you.

Cars, trucks, bikes and motorcycles are all substitutable goods. That’s why, if we’re competent drivers or riders, we can switch between them. It’s why we can bring what’s ours (our wallets and other personal things) with us in any variety of vehicles, without worrying about whether those personal things are compatible with a maker’s proprietary driving system.

And, because we are independent as drivers and riders, we are better able to relate to everybody and everything our vehicles enable us to reach and engage. Vehicles are, literally, tools of independence and engagement.

Nobody has invented a car for the Net or the Web yet. Browsers could have been cars, but they have remained stuck for sixteen years in the calf-cow slave-master world of the client-server model. That’s not the Net’s model, or the Web’s, either. It’s just what we’ve used for so long that we can hardly imagine anything else.

Think about how you feel on your bike, or in your car or truck. That’s what we want online. We don’t have it yet, so let’s invent it.

Some background

The World Wide Web was designed originally as a way to link documents by hypertext. Like the Internet it still runs on, it was end-to-end. At the ends were documents and (presumably) readers.

The World Wide Web was designed originally as a way to link documents by hypertext. Like the Internet it still runs on, it was end-to-end. At the ends were documents and (presumably) readers.

The commercial Web of today is something else: a collection of sites. All are real estate: domains, literally. Each site doing business (and there are now a billion or more of those) has its own terms of engagement. Visitors can take or leave them. Either way, visitors’ freedom within each domain is entirely submissive in respect to the site owner.

This is an architectural fact of life on the commercial Web. It’s also why, should we wish to do business with the site owner, we meet an agreement that looks like this…

You agree that we aren’t liable for annoying interruptions caused by you; or a third party, buildings, hills, network congestion, rye whiskey falling sickness or unexpected acts of God or man, or of Elvis leaving the building. Unattended overseas submissions in saved mail hazard functions will be subject to bad weather or sneeze funneling through contractor reform blister pack truncation, or for the duration of the remaining unintended contractual subsequent lost or expired obligations, except in the state of Nevada at night. We also save harmless ourselves and close relatives from all we don’t control; including clear weather and acts of random gods. You also agree that we are not liable for missed garments, body parts, or voice mails, even if you have saved them. Nothing we say or mumble here is trustworthy or true, or meant for any purpose other than to feed the fears of our legal department, which has no other reason to live. Whether for reasons of drugs, hormones, gas or mood, we may change terminate this agreement with cheerful impunity, and notify you by means that neither of us will respect or remember.

☐ Accept.

… and click on the box.

“Agreements” like this are known in the legal trade as standard form or adhesion contracts. According to West’s Encyclopedia of American Law, this form “offers goods or services to consumers on essentially a ‘take it or leave it’ basis without giving consumers realistic opportunities to negotiate terms that would benefit their interests. When this occurs, the consumer cannot obtain the desired product or service unless he or she acquiesces to the form contract.” In other words, we acquiesce to these:

These contracts are called “adhesive” because they lock the submissive party to an agreement which the dominant party can change whenever it wants. In “Contracts of Adhesion—Some Thoughts about Freedom of Contract” (Columbia Law Review, July 1943), Friedrich Kessler explains how these contracts came to be:

The development of large scale enterprise with its mass production and mass distribution made a new tvpe of contract inevitable—the standardized mass contract. A standardized contract, once its contents have been formulated by a business firm, is used in every bargain dealing with the same product or service. The individuality of the parties which so frequently gave color to the old type contract has disappeared. The stereotyped contract of today reflects the impersonality of the market. It has reached its greatest perfection in the different types of contracts used on the various exchanges. Once the usefulness of these contracts was discovered and perfected in the transportation, insurance, and banking business, their use spread into all other fields of large scale enterprise, into international as well as national trade, and into labor relations.

Half a century later, that same perfection has spread across the commercial Web as well. For example, take Google’s Terms of Service. Here’s an excerpt:

2. Accepting the Terms

2.1 In order to use the Services, you must first agree to the Terms. You may not use the Services if you do not accept the Terms.

2.2 You can accept the Terms by:

(A) clicking to accept or agree to the Terms, where this option is made available to you by Google in the user interface for any Service; or

(B) by actually using the Services. In this case, you understand and agree that Google will treat your use of the Services as acceptance of the Terms from that point onwards.

The parts I’ve italicized translate to use = agreement.

There is also this:

19. Changes to the Terms

19.1 Google may make changes to the Universal Terms or Additional Terms from time to time. When these changes are made, Google will make a new copy of the Universal Terms available at http://www.google.com/accounts/TOS?hl=en and any new Additional Terms will be made available to you from within, or through, the affected Services.

Every site and service has the same kind of jive. Here’s foursquare’s:

Modification of Terms of Use.

foursquare reserves the right, at its sole discretion, to modify or replace any of these Terms of Use, or change, suspend, or discontinue the Service (including without limitation, the availability of any feature, database, or content) at any time by posting a notice on the Site or by sending you notice through the Service or via email. foursquare may also impose limits on certain features and services or restrict your access to parts or all of the Service without notice or liability. It is your responsibility to check these Terms of Use periodically for changes.

These are what I call the “Vogon clauses.” Readers of Douglas Adams’ The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy will recall that Earth was destroyed without warning by Vogons (the galaxy’s bureaucrats) to make way for a hyperspace express route. Plans for the route, Vogons explained, had been available at the local planning department near Alpha Centauri for fifty years before the wrecking ships came through.

Ah, but that’s not all. Terms of Service are usually accompanied by Privacy Policies. foursquare’s, again, is typical:

Sharing with Partners, in connection with business transfers, and for the protection of foursquare and others:

- Our Partners: In addition to the data sharing described above, we enter into relationships with a variety of businesses and work closely with them. In certain situations, these businesses sell items or provide promotions to you through foursquare’s Service. In other situations, foursquare provides services, or sells products jointly with these businesses. You can easily recognize when one of these businesses is associated with your transaction, and we will share your Personal Information that is related to such transactions with that business, unless you have elected not to be solicited by marketing partners during the registration process or through the account settings page.

- Business Transfers: If foursquare or substantially all of its assets are acquired, or in the unlikely event that foursquare goes out of business or enters bankruptcy, user information would be one of the assets that is transferred or acquired by a third party.

- Protection of foursquare and Others: We may release Personal Information when we believe in good faith that release is necessary to comply with the law, including laws outside your country of residence; enforce or apply our conditions of use and other agreements; or protect the rights, property, or safety of foursquare, our employees, our users, or others. This includes exchanging information with other companies and organizations (including outside of your country of residence) for fraud protection and credit risk reduction.

The italicized passage is the loophole through which every bit of information about you, your checkins, your friends, your tips, your mayoralty of the crosstown bus and the corner dry cleaner — all of it — can fly off to Lyrfmstrdl.com or some other acquisitor, which will be free of foursquare’s burden of good intentions toward your privacy.

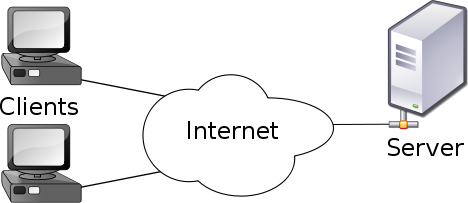

The client–server model of computing is a distributed application structure that partitions tasks or workloads between the providers of a resource or service, called servers, and service requesters, called clients.

They illustrate that with this generic drawing:

Thus, while the Net itself has a design in which all the ends are essentially peers, the Web (technically an application on the Net) has a submissive-dominant design in which clients submit to servers in the manner of calves to cows:

As calves, we get the milk made from html, javascript, XML and other document-authoring standards; plus, in most cases, cookies as well.

The original idea behind cookies was helping a site remember where you both were the last time the last time your browser suckled on the site’s teat. That’s how you can get straight to your shopping cart, your account data and other graces of modern consumer husbandry. It’s one way your browser turns into one big personalized single-store superset of a shopping cart in each commercial site you visit. It’s also how you get “personalized” advertising, plus all the other good and bad stuff that Eli Pariser visits in The Filter Bubble.

We also aren’t going to get rid of the calf-cow system, and we can’t improve it any more than we can improve slavery. There is no hack on submissive-dominant that can make it peer-to-peer.

If we wish to leverage the original peer-to-peer nature of the Net and the Web, we will need new instruments of independence and autonomy, that also allow us to engage as equals, and to form relationships that are worthy of the noun. What would those be?

When the first browsers came along from Netscape (and then Microsoft), my wife asked a question that challenged a premise of browsers, and of Web-server-based commerce. “Why can’t I take my shopping cart from one site to another?”

The reason was, and still is, that each site has its own shopping cart, and comprehends you as their customer alone. (I’ve italicized the first person possessive pronoun there.) Even if the commercial site is Orbitz or Travelocity, you can’t take your preferences, your settings or anything else from one of those to another. You are trapped on each one’s ranch.

Offline in the brick-and-mortar world, retailers have copied this system through loyalty programs and other instruments of customer entrapment. But at least in the brick-and-mortar world we still have our own vehicles, including our feet.We are independent by nature.

But we are not yet independent on the commercial Web. Sellers have hijacked the browser and made it theirs, not ours.

So, then

Taking browsers back isn’t the challenge.* The best we can do is improve what will never be good enough. What we need instead are vehicles that give us both independence and means for engagement.

Work in this direction has been going on in the ProjectVRM development community from the start, and a big thanks goes to the Berkman Center for giving us the runway we needed to get that community off the ground. A lot of the necessary tools we’ll need are already there (or in the free and open source code toolbox), or on their way.

But we still don’t have the equivalent of a bike, a car, a motorcycle, a truck, or our own two feet. We just have clients of servers.

Thus, in the absence of our own means of ambulation and locomotion, we continue to talk about how we make slavery easier while improving the ranching system. That’s good and essential work, but it’s not enough. We need to get creative for ourselves now. Not just for the Big Ranchers of today and tomorrow.

* [Later…] I’ve gotten some good push-back on this from members of the VRM community that have more hope for browsers than I do. They also point out that browsers have 100% market penetration, and lots of enlightened developers on the case. We should engage them and not dis them. I agree.