Don’t think about what’s wrong on the Web. Think about what pays for it. Better yet, look at it.

Start by installing Privacy Badger in your browser. Then look at what it tells you about every site you visit. With very few exceptions (e.g. Internet Archive and Wikipedia), all are putting tracking beacons (the wurst cookie flavor) in your browser. These then announce your presence to many third parties, mostly unknown and all unseen, at nearly every subsequent site you visit, so you can be followed and profiled and advertised at. And your profile might be used for purposes other than advertising. There’s no way to tell.

This practice—tracking people without their invitation or knowledge—is at the dark heart and sold soul of what Shoshana Zuboff calls Surveillance Capitalism and Brett Frischmann and Evan Selinger call Re-engineering Humanity. (The italicized links go to books on the topic, both of which came out in the last year. Buy them.)

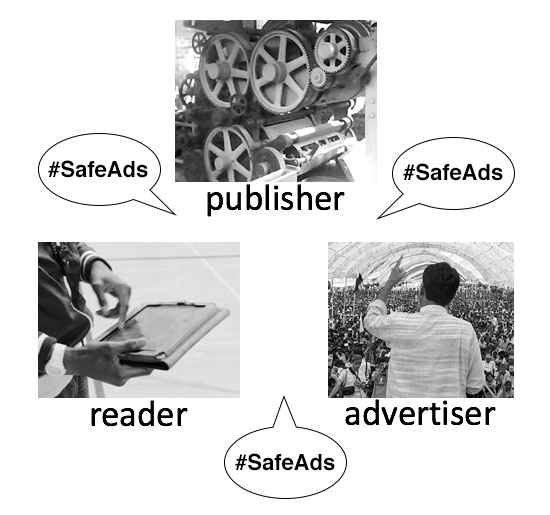

While that system’s business is innocuously and misleadingly called advertising, the surveilling part of it is called adtech. The most direct ancestor of adtech is not old fashioned brand advertising. It’s direct marketing, best known as junk mail. (I explain the difference in Separating Advertising’s Wheat and Chaff.)

In the online world, brand advertising and adtech look the same, but underneath they are as different as bread and dirt. While brand advertising is aimed at broad populations and sponsors media it considers worthwhile, adtech does neither. Like junk mail, adtech wants to be personal, wants a direct response, and ignores massive negative externalities. It also uses media to mark, track and advertise at eyeballs, wherever those eyeballs might show up. (This is how, for example, a Wall Street Journal reader’s eyeballs get shot with an ad for, say, Warby Parker, on Breitbart.) So adtech follows people, profiles them, and adjusts its offerings to maximize engagement, meaning getting a click. It also works constantly to put better crosshairs on the brains of its human targets; and it does this for both advertisers and other entities interested in influencing people. (For example, to swing an election.)

For most reporters covering this, the main objects of interest are the two biggest advertising intermediaries in the world: Facebook and Google. That’s understandable, but they’re just the tip of the wurstberg. Also, in the case of Facebook, it’s quite possible that it can’t fix itself. See here:

How easy do you think it is for Facebook to change: to respond positively to market and regulatory pressures?

Consider this possibility: it can’t.

One reason is structural. Facebook is comprised of many data centers, each the size of a Walmart or few, scattered around the world and costing many $billions to build and maintain. Those data centers maintain a vast and closed habitat where more than two billion human beings share all kinds of revealing personal shit about themselves and each other, while providing countless ways for anybody on Earth, at any budget level, to micro-target ads at highly characterized human targets, using up to millions of different combinations of targeting characteristics (including ones provided by parties outside Facebook, such as Cambridge Analytica, which have deep psychological profiles of millions of Facebook members). Hey, what could go wrong?

In three words, the whole thing.

The other reason is operational. We can see that in how Facebook has handed fixing what’s wrong with it over to thousands of human beings, all hired to do what The Wall Street Journal calls “The Worst Job in Technology: Staring at Human Depravity to Keep It Off Facebook.” Note that this is not the job of robots, AI, ML or any of the other forms of computing magic you’d like to think Facebook would be good at. Alas, even Facebook is still a long way from teaching machines to know what’s unconscionable. And can’t in the long run, because machines don’t have a conscience, much less an able one.

You know Goethe’s (or hell, Disney’s) story of The Sorceror’s Apprentice? Look it up. It’ll help. Because Mark Zuckerberg is both the the sorcerer and the apprentice in the Facebook version of the story. Worse, Zuck doesn’t have the mastery level of either one.

Nobody, not even Zuck, has enough power to control the evil spirits released by giant machines designed to violate personal privacy, produce echo chambers beyond counting and amplify tribal prejudices (including genocidal ones)—besides whatever good it does for users and advertisers.

The hard work here is lsolving the problems that corrupted Facebook so thoroughly, and are doing the same to all the media that depend on surveillance capitalism to re-engineer us all.

Meanwhile, because lawmaking is moving apace in any case, we should also come up with model laws and regulations that insist on respect for private spaces online. The browser is a private space, so let’s start there.

Here’s one constructive suggestion: get the browser makers to meet next month at IIW, an unconference that convenes twice a year at the Computer History Museum in Silicon Valley, and work this out.

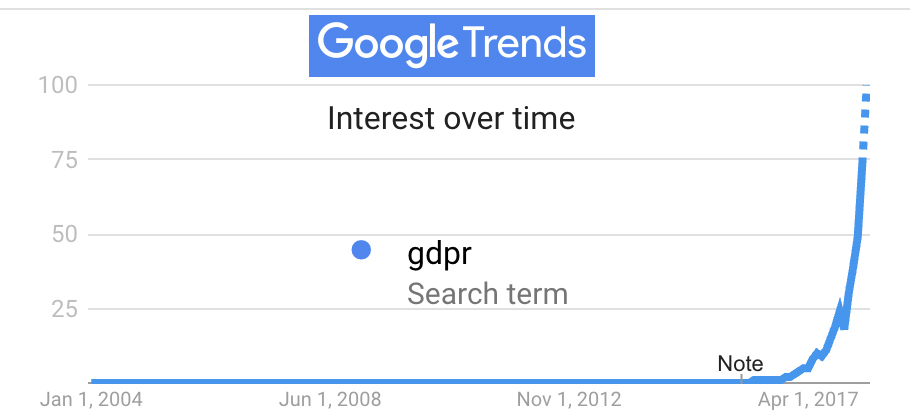

Ann Cavoukian (@AnnCavoukian) got things going on the organizational side with Privacy By Design, which is now also embodied in the GDPR. She has also made clear that the same principles should apply on the individual’s side. So let’s call the challenge there Privacy By Default. And let’s have it work the same in all browsers.

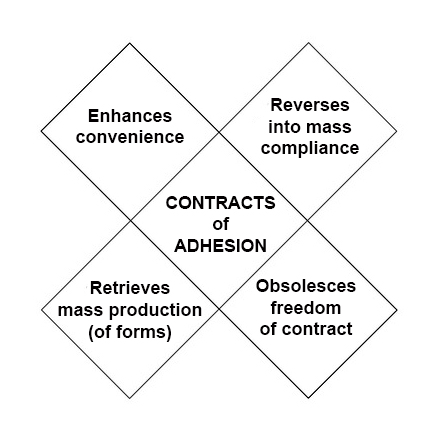

I think it’s really pretty simple: the default is no. If we want to be tracked for targeted advertising or other marketing purposes, we should have ways to opt into that. But not some modification of the ways we have now, where every @#$%& website has its own methods, policies and terms, none of which we can track or audit. That is broken beyond repair and needs to be pushed off a cliff.

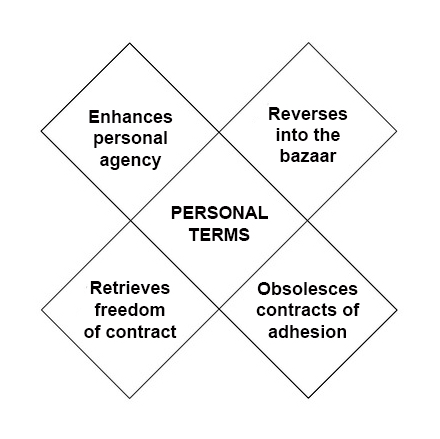

Among the capabilities we need on our side are 1) knowing what we have opted into, and 2) ways to audit what is done with information we have given to organizations, or has been gleaned about us in the course of our actions in the digital world. Until we have ways of doing both, we need to zero-base the way targeted advertising and marketing is done in the digital world. Because spying on people without an invitation or a court order is just as wrong in the digital world as it is in the natural one. And you don’t need spying to target.

And don’t worry about lost business. There are many larger markets to be made on the other side of that line in the sand than we have right now in a world where more than 2 billion people block ads, and among the reasons they give are “Ads might compromise my online privacy,” and “Stop ads being personalized.”

Those markets will be larger because incentives will be aligned around customer agency. And they’ll want a lot more from the market’s supply side than surveillance based sausage, looking for clicks.

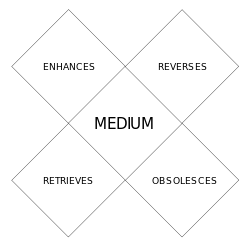

ProjectVRM an award (there on the right) that was way ahead of its time.

ProjectVRM an award (there on the right) that was way ahead of its time.