Here’s an overdue compilation of stuff I’ve been saving up to share. Many items have slipped through the cracks, but I want to get at least these up.

The plural of personal is social, by JP Rangaswami. The punchlines (read through — there are many):

Business is personal. It’s about relationships. It has always been so. Until we tried to forget it and concentrated on making money, not shoes. [As Peter Drucker said, people make shoes, not money]. Then, for a short while, business became not-personal.

As the Cluetrain guys signalled way back in 1999, the web was changing all that. Business was becoming personal again.

It comes as no surprise to me that salesforce.com was born during those heady times, as business started becoming personal again. It comes as no surprise to me that Marc Benioff understood that the plural of personal is social, and that it’s in the DNA of the company that he and Parker Harris founded. That’s why I went to work for them.

“Social” is not a layer. “Social” is not a feature. “Social” isn’t a product.

Social is about bringing being human back into business. About how we conduct business. About why we conduct business.

Social is something in people’s hearts, in people’s beings, in their DNA.

Man is born social.

Many companies were not.

And the companies that weren’t, they can’t just become social by buying layers or features or even products. Porcine unguents, nothing more.

You need to be reborn social.

You need to start thinking of the customer as someone to have a relationship with, to get to know, to invest in, to trust, to respect.

And you need to get everyone in the company to think that way, to act that way, in everything they do.

And you need to do this everywhere, not just with your customers. Not just with your supply web or your trading partners. Not just with your staff and your consultants.

Everyone. Everywhere.

The plural of personal is social.

Proof That Loyalty Is For Suckers: Best Customers Get Penalized With Higher Bills, by Brad Tuttle in Time. It begins,

We appreciate your business. And as thanks for being a loyal customer all these years, we’re going to overcharge you.

Auto insurers and other service providers don’t say this explicitly, of course. But that’s the message sent via the rates they charge different customers.

The curious, but obviously profitable business model, in which new customers get wooed with discounts and special deals, while the oldest, most loyal, best customers are “thanked” with bills that escalate over time, is standard practice among pay TV and wireless providers. The companies play up the idea that their products and services come with special introductory rates for new customers, rather than noting that there are penalties for customers who stick with the business for the long haul and don’t complain. But no matter which way the rate changes are spun, the results are the same.

Some VRooM-ish tools and services:

- YaCy: “Web search by the people, for the people.” Some copy: “YaCy is a free search engine that anyone can use to build a search portal for their intranet or to help search the public internet. When contributing to the world-wide peer network, the scale of YaCy is limited only by the number of users in the world and can index billions of web pages. It is fully decentralized, all users of the search engine network are equal, the network does not store user search requests and it is not possible for anyone to censor the content of the shared index. We want to achieve freedom of information through a free, distributed web search which is powered by the world’s users.”

- Tails: “The amnesiac incognito live system.” Copy: “It helps you to use the Internet anonymously almost anywhere you go and on any computer but leave no trace using unless you ask it explicitly.”

- Silent Circle: “Private encrypted communications tools.” Email, mobile phone, VoIP, text. Scroll down to founders & leadership. One is Phil Zimmerman, father of PGP.

- Request Policy is “an extension for Mozilla browsers that increases your browsing privacy, security, and speed by giving you control over cross-site requests.”

Market Research (MR to its denizens) gets an earful about VRM and The Intention Economy in

The 21st Century Battle for the Future of MR has begun: Empowered Consumers Versus “Darth Data”, by Kevin Lonnie in The Greenbook Blog.

I see some hope for getting more digital books out of silos in An RDF for Books, by Brian O’Leary.

For the privacy corner of VRM, dig Privacy, Masks and Religion, by Omer Tene in Concurring Opinions. It begins, “One of the most significant developments for privacy law over the past few years has been the rapid erosion of privacy in public.”

Klint Finley in TechCrunch makes some right-on observations about The Cloud, though he says “there being a few examples of … “vendor relationship management” idea in the wild, it still feels like vaporware to me.” Obviously I think he’s wrong, but we report the negative stuff here too. On the positive side, Scott Merrill wrote Doc Searls Would Like You to Join Him in the The Intention Economy, also in TechCrunch, back in May.

From Selling You: Not Just on Facebook, by Haydn Shaughnessy writes this in Forbes:

The reality is we need a different way of thinking about data, and in an age marked by innovation we shouldn’t find a reframe too difficult. We shouldn’t but we do. Generations of marketers have been brought up on an adversarial view of the customer, the target, the win…

In all the discussions we’ve had here in Forbes about social business we have yet to stray into the use and purpose of social data, as if we too largely accept that the adversarial view is the only one.

A couple of days back I tried to reflect an alternative view in for, example, how we might use LinkedIn data – it’s not only my view of course and I don’t want to claim any originality in it. For five years or more, maybe as far back as The ClueTrain Manifesto, people like Doc Searls have been arguing that the web makes a better commerce engine if we recognize all the power symmetries it brings. And there is an increasing number of projects that are taking up that logic.

CRM type data is old school – Tesco in the UK had signed up more than 15 million people to its ClubCard by 2009, that is over a third of the adult population of the country. It’s what companies did before the web. But it seems to be continuing even now that we have new possibilities.

There is no need to collect inference data on people and their possible choices. There is no adversary called customer. We have scaled up human interaction online where we can get closer to asking people, suggesting to them, and interacting with them.

So the future actually belongs to companies that take a symmetrical view of power…

From Another Bubble; Not Housing, by Francine Hardaway of Stealthmode Blog in Business Insider:

Guys, we ARE in a bubble. I don’t care what you say. As an outsider, I can see it…

Like Facebook, Pinterest and Instgram have valuations that are guesses about the future of advertising.Will they be the next great places to advertise as we shift to mobile?

Pinterest may be worth more “nothing” than Instgram, however, because as Scoble pointed out, women have buying power, which is why brands cozy up to mommy bloggers. But they haven’t bought BlogHer, the platform on which those women express opinions, have they? Lisa, Jory and Elisa were pioneers in bringing women’s voices to the marketplace, and no one has offered them a billion. That’s because BlogHer is not a tool. But it should expose also the fact that simply being favored by women doesn’t confer $7b in value on a company.

More worrisome is the supposition that these apps will someday be good carriers of mobile advertising, even though as yet the advertising industry hasn’t solved the online ad effectiveness problem and even Facebook reported diminished revenues this quarter.

The advertising industry is in upheaval, over the value of online advertising per se, before it even tackles mobile. Publishers are going under right and left because customers don’t want to see ads online, and truly hate them on mobile . Here, especially, the user will control the conversation.

So the valuations of Pinterest and Instgram/FB are merely expensive guesses about the future of advertising, about whether the ad tech industry will figure out mobile in a non-invasive way. Yes, the open graph will be part of it, and the advertising will be targeted. But I am guessing that Doc Searls will be quoted here gain and again: markets are conversations, and customers will control them.

In Vendor Relationship Management: Making the Customer King, Stephen F. DeAngelis visits both The Intention Economy and The Customer As a God (my Wall Street Journal essay from July)

Companies and customers need to be able to deal with each other in two ways: as individuals and as groups.

Companies and customers need to be able to deal with each other in two ways: as individuals and as groups.

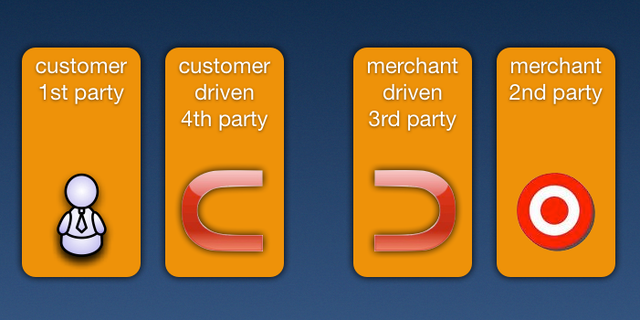

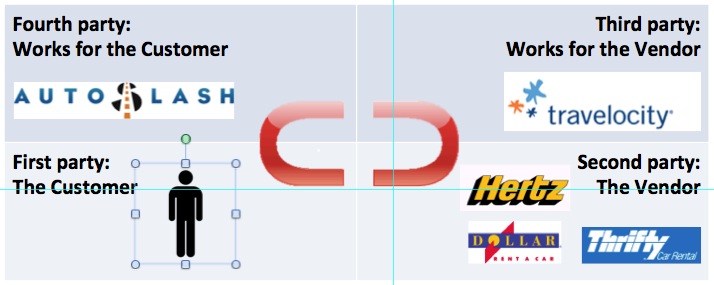

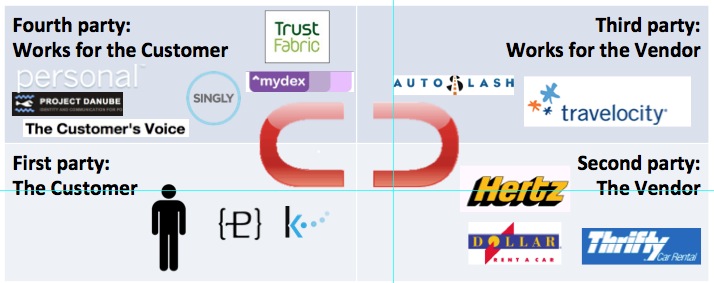

As of today AutoSlash presents itself as an agent of the customer, but business-wise it’s an accessory to a third party, Travelocity. While Travelocity could be a fourth party as well, it is still too tied into the selling systems of the car rental agencies to make the move. (If I’m wrong, tell me how.) Now, what if AutoSlash were to join a growing young ecosystem of VRM companies and projects working on the customer’s side? Here is roughly how that looks today:

As of today AutoSlash presents itself as an agent of the customer, but business-wise it’s an accessory to a third party, Travelocity. While Travelocity could be a fourth party as well, it is still too tied into the selling systems of the car rental agencies to make the move. (If I’m wrong, tell me how.) Now, what if AutoSlash were to join a growing young ecosystem of VRM companies and projects working on the customer’s side? Here is roughly how that looks today:  AutoSlash is over there on the right, on the sell side. On the buy side, in the fourth party quadrant, are

AutoSlash is over there on the right, on the sell side. On the buy side, in the fourth party quadrant, are

For as long as we’ve had economies, demand and supply have been attracted to each other like a pair of magnets. Ideally, they should match up evenly and produce good outcomes. But sometimes one side comes to dominate the other, with bad effects along with good ones. Such has been the case on the Web ever since it went commercial with the invention of the cookie in 1995, resulting in a

For as long as we’ve had economies, demand and supply have been attracted to each other like a pair of magnets. Ideally, they should match up evenly and produce good outcomes. But sometimes one side comes to dominate the other, with bad effects along with good ones. Such has been the case on the Web ever since it went commercial with the invention of the cookie in 1995, resulting in a