The Castle doctrine has been around a long time. Cicero (106–43 BCE) wrote, “What more sacred, what more strongly guarded by every holy feeling, than a man’s own home?” In Book 4, Chapter 16 of his Commentaries on the Laws of England, William Blackstone (1723–1780 CE) added, “And the law of England has so particular and tender a regard to the immunity of a man’s house, that it stiles it his castle, and will never suffer it to be violated with impunity: agreeing herein with the sentiments of ancient Rome…”

Since you’re reading this online, let me ask, what’s your house here? What sacred space do you strongly guard, and never suffer to be violated with impunity?

At the very least, it should be your browser.

But, unless you’re running tracking protection in the browser you’re using right now, companies you’ve never heard of (and some you have) are watching you read this, and eager to use or sell personal data about you, so you can be delivered the human behavior hack called “interest based advertising.”

Shoshana Zuboff, of Harvard Business School, has a term for this:surveillance capitalism, defined as “a wholly new subspecies of capitalism in which profits derive from the unilateral surveillance and modification of human behavior.”

Almost across the board, advertising-supported publishers have handed their business over to adtech, the surveillance-based (they call it “interactive”) wing of advertising. Adtech doesn’t see your browser as a sacred personal space, but instead as a shopping cart with ad space that you push around from site to site.

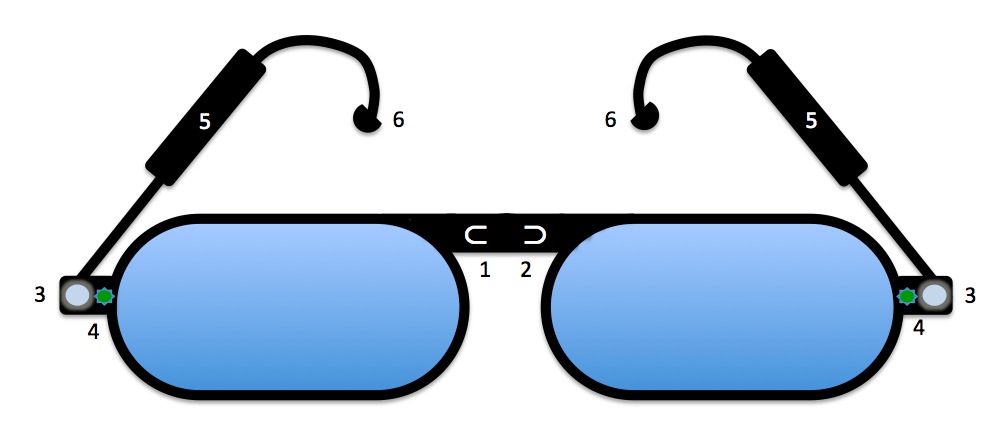

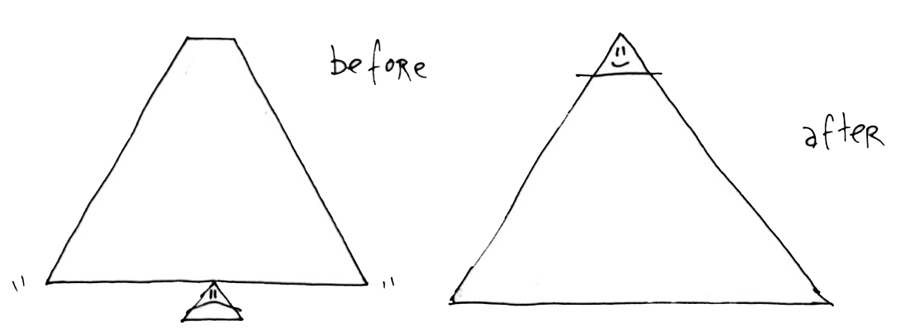

So here is a helpful fact: we don’t go anywhere when we use our browsers. Our browser homes are in our computers, laptops and mobile devices. When we “visit” a web page or site with our browsers, we actually just request its contents (using the hypertext protocol called http or https).

In no case do we consciously ask to be spied on, or abused by content we didn’t ask for or expect. That’s why we have every right to field-strip out anything we don’t want when it arrives at our browsers’ doors.

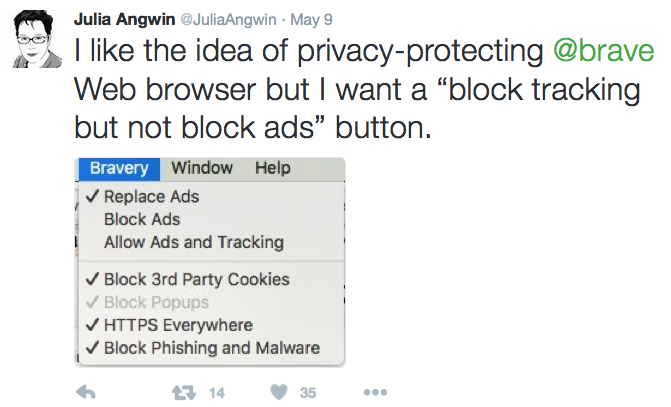

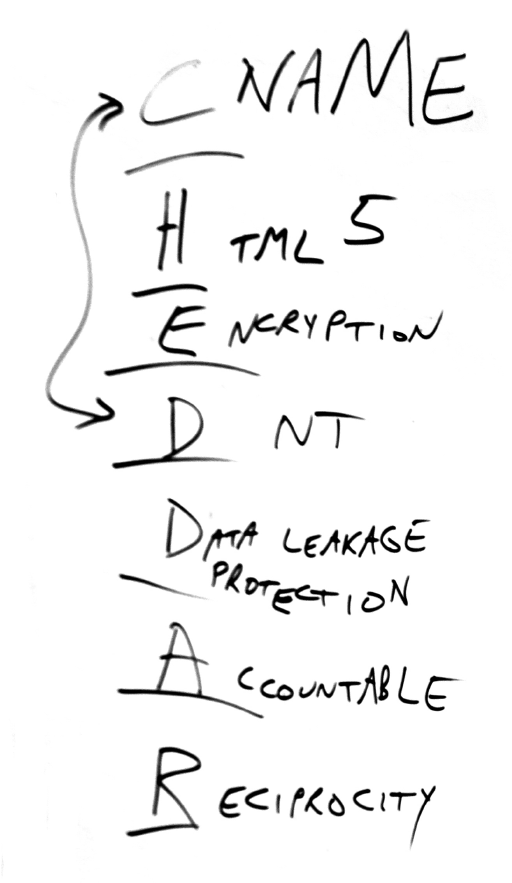

The castle doctrine is what hundreds of millions of us practice when we use tracking protection and ad blockers. It is what called the new Brave browser into the marketplace. It’s why Mozilla has been cranking up privacy protections with every new version of Firefox . It’s why Apple’s new content blocking feature treats adtech the way chemo treats cancer. It’s why respectful publishers will comply with CHEDDAR. It’s why Customer Commons is becoming the place to choose No Trespassing signs potential intruders will obey. And it’s why #NoStalking is a good deal for publishers.

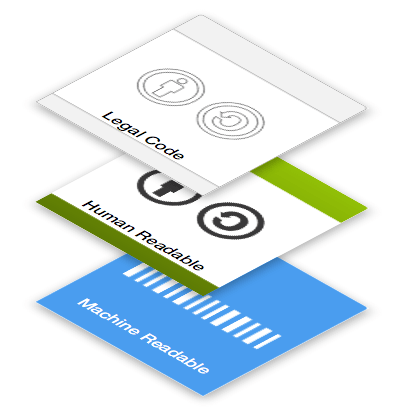

The job of every entity I named in the last paragraph — and every other one in a position to improve personal privacy online — is to bring as much respect to the castle doctrine in the virtual world as we’ve had in the physical one for more than two thousand years.

It should help to remember that it’s still early. We’ve only had commercial activity on the Internet since April 1995. But we’ve also waited long enough. Let’s finish making our homes online the safe places they should have been in the first place.

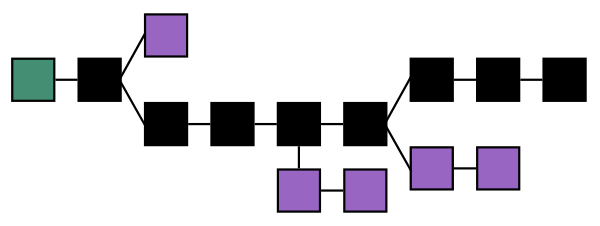

In

In  Meerkat

Meerkat Periscope

Periscope