I’m at SmallData NYC, hosted by Mozilla. What I’m writing here is not a report on the event (which will be up on the Web for all to see, soon enough), but rather my own #VRM-based riffs on what the panelists (and later the audience) are saying. The purpose of an event like this is to get people thinking and talking. So that’s what I’m doing here.

- New word for me: deconvolve. I like it, but gotta look it up.

- Actual and clear intent is more valuable than inferred intent.

- Whatever happened to AskJeeves-type search? Such as “I’m looking for Michael Jordan the AI expert, not the basketball player.”

- Thought: Why does search have to be so effing complicated.

- The Net has no business model. That’s why it supports an infinitude of business.

- At the moment a common (if not prevailing) business model on the Web is surveillance-based personalized advertising. This is not the same thing as the Web itself. If protecting your privacy, or “becoming an exile” from surveillance fails to support this business model, it does not break the model so much as provide feedback on what isn’t working — or what else might work better. And it certainly does not “break the Web.”

- “The Industry” is an interesting term. (One of the panelists “speaks for the industry.” I think here it means “commercial players on the Web.” In Hollywood it means Hollywood. I don’t think we’re even close to that level of metonymic maturity.

- “Small animal taxidermy is specifically an eBay problem.” I think I just heard that.

- I like “giving a user recommendations that are out of the cone of relevance.”

- Cone of Relevance is a good name for a band.

- Netflix recommendations are at least partly (or largely) about developing a long-term relationship with the company. Keeping subscribers. “If you know Netflix knows you, you’ll stay.”

- Battlestar Gallactica, by pure numbers, has high correlations with a children’s show for 3 year olds. Possibly because watchers of the show have little kids. “The math works,” but the manners don’t.

- On break, I’m with @Deanland, who sez, “All they seem to care about is how to glean information from people for the benefit of the sell side, with no discussion or apparent thinking about what the user wants, feels, means or cares about. The data is on a one-way street from buyer to seller, but only for the benefit of the seller, not the benefit of the buyer. Saying ‘It’s about serving them better’ actually means ‘We can sell them better.’ There is also a sense that it is a given that The Machine, run by the seller, can get all this information, with no conscious involvement at all by the people yielding the information.” (Hoping Dean — and others — will bring this up after the break. We’ve only had presentations so far, not discussions yet.)

- Also from the audience on break: “We need a personal data silo. For the person, the #smalldata holder — not the marketing machine.”

- Wendy Davis of Mediapost (moderator) is challenging the apparent belief, by the panel, that more information about individuals held by companies is better for individuals. (I think she’s saying.)

- I’m a person. I want my to do my own damn personalization. Just saying.

- David Sontag, panelist, says usage data with Internet Explorer all goes to Microsoft.

- “People get much more upset with bad personalization than no personalization.” (Not sure I got that down right.)

- Chris Maliwat, panelist: It’s sometimes hard to perceive a company’s intentionality.

- All these companies are in the train business. We’re passengers, whether we like it or not. Meanwhile, what we need are cars: instruments of independence, agency and personal utility — for ourselves, following our own intentions. I believe Mozilla is the only major browser that can fill this role, because it’s on our side and not on these companies’ side. The other browsers are all instruments of their parent companies.

- A reason people don’t get more creeped out by all this surveillance and personalization, is that there have not yet been clear, big, news-making harms. Once that happens, the game changes.

- David Sontag: “I can ‘t get a credit card that won’t share my information with other companies.”

- Wendy: “How do researchers get users’ true intent?” (e.g. her gender may be irrelevant to her search, but The System notes her gender anyway)

- Chris: Personalization is not about perfection, but about providing a range of choices.

- Wendy: “Do people actually know what they want?” My answer: yes. And the assumption that people mostly don’t know is a flaw in The System. So is the assumption that we are in the market to buy stuff all the time. If I want to know the height of Mt. Everest, that doesn’t mean I want to go there, or buy mountaineering gear, or anything commercial.

- Pat, from the audience, on intelligibility of recommendations: Pandora has filters that are domain aware… But lack of domain makes it harder to make recommendations intelligible.

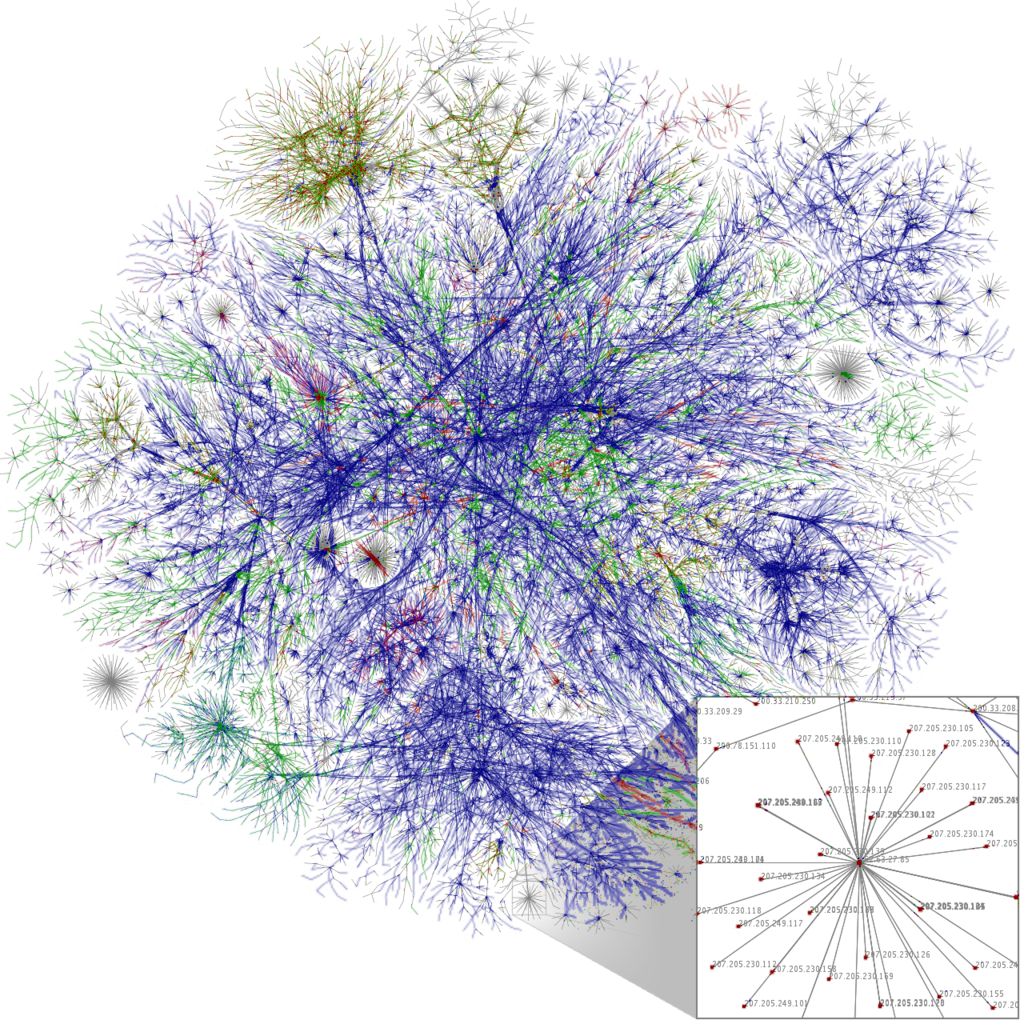

- So far all of this is inside baseball. Except the game isn’t baseball. It’s building out the system in Minority Report. But instead of “pre-crime,” it’s all about what we might call “pre-sales.” It’s this scene here.

- The panel conversation is currently (I think) about the user’s intent “being understood.” So I find myself channeling Walt Whitman: I know that I am august. I do not trouble my spirit to vindicate itself or be understood. I see that the elementary laws never apologize. Also, Do I contradict myself? Very well then. I contradict myself. I am large. I contain multitudes… The spotted hawk swoops by and accuses me. He complains of my gab and my loitering. I too am not a bit tamed. I too am untranslatable. I sound my barbaric yawp over the roofs of the world. I feel one of those yawps rising in me now.

- A question from the back of the room for “opt in, rather than opt out.” (Of tracking and all that.)

- Chris’s reply: “Google already exists.” The point is that Google and today’s Web giants are the environment. Deal with it.

- Audience guy: There is an imbalance between their control and mine as an individual. Right.

- Wendy: Targeting based on zip code isn’t especially personal. But what we’re talking about here is very personal. Doesn’t this raise issues?

- Slobodan: Maybe the Net will become more like the insurance business. (Did I hear that right? Missed the point, though.)

- Audience guy: What kinds of restraint exists now for users that don’t care about privacy at all — as with some young people.?

- I stirred things up a bit at the end (my barbaric yawp, you might say), but it’s over now, so I’ll need to do my own wrapping later.

Currently 9:15pm, EDST.

Okay, next day, 5pm.

I had hoped that Dean, quoted above, would be called, but he wasn’t, so I raised my hand and said that what the panel had talked about up to that point was mostly inside baseball — a metaphor that at least Chris wasn’t clear on, because he asked me what I meant by it. What I meant was that all three of the panelists were inside The Industry. And what I tried then to do was get them to stand on the other side, the individual’s side, and look at what they do from that angle. When they asked what was being done on the individual’s side, I brought up VRM development, and volunteered Kenneth Lefkowitz of Emmett Global to speak as a VRM developer. Which he did.

So that was it, or as close as I’m going to get in a blog post. When the event goes up on the Web, I’ll add the links.

You can see that the leather, laces and stitching are all fine. So is the wool lining. The problem is the sole. It has dried up and cracked into pieces. Every time I wear it, chunks fall off. In fact, I first thought about writing this when a piece of a heel with a LAMO logo on it looked up at me from under my desk. But I’m wearing them now, and I’ll probably keep wearing them after the soles come off completely. I would like to help LAMO learn from my experience. As of today, here are the four main choices for that:

You can see that the leather, laces and stitching are all fine. So is the wool lining. The problem is the sole. It has dried up and cracked into pieces. Every time I wear it, chunks fall off. In fact, I first thought about writing this when a piece of a heel with a LAMO logo on it looked up at me from under my desk. But I’m wearing them now, and I’ll probably keep wearing them after the soles come off completely. I would like to help LAMO learn from my experience. As of today, here are the four main choices for that:

We need first person technologies for the same reason we need first person voices: because there are some things only a person can say and do.

We need first person technologies for the same reason we need first person voices: because there are some things only a person can say and do.