As of today, ProjectVRM is eight years old.

So now seems like a good time for a comprehensive (or at least long) report on what we’ve been doing all this time, how we’ve been doing it, and what we’ve been learning along the way.

ProjectVRM has always been both a group effort and provisional in its outlook and methods. So look at everything below as a draft requiring improvement, and send me edits, either by email (dsearls at cyber dot law dot harvard dot edu) or by commenting below.

Summary

After eight years of encouraging development of tools and services that make individuals both independent and better able to engage, ProjectVRM (VRM stands for vendor relationship management) is experiencing success in many places; most coherently in France, the UK and Oceania (Australia and New Zealand). There are now dozens of VRM developers (though many descriptors besides VRM are used), and investor interest is shifting from the “push” to the “pull” side of the marketplace. Government encouragement of VRM is strongest in the UK and Australia. ProjectVRM and its community are focused currently on “first person” technologies, privacy, trust, identity (including anonymity), relationship (including experience co-creation), substituability of services and the Internet of Things. Verticals are personal information management, relationship (VRM+CRM), identity, on-demand services, payments, messaging (e.g. secure email), health, automotive and real estate. There are many possibilities for research, possibly starting with the effects on business of individuals being in full control of their sides of agreements with companies.

Here are shortcuts to each section:

- History

- Development

- Community

- Influence

- Issues

- Verticals

- Investment

- Research

- Questions

1. History

ProjectVRM is one of many research projects at the Berkman Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University. It started when I began a four-year fellowship at Berkman in September, 2006. In those days Berkman fellows were encouraged to work on a project. I had lots of guidance from Berkman staff and other veterans; but what best focused my purpose was something Terry Fisher said at one of the orientation talks. He said Berkman did its best to be neutral about the subjects it studies, but also that “we do look for effects.”

The effect-generating work for which I was best known at the time was The Cluetrain Manifesto, which I co-authored seven years earlier with Chris Locke, David Weinberger and Rick Levine. By most measures Cluetrain was a huge success. The original website launched a meme that won’t quit, and the book that followed was a bestseller.(It still sells well today). But I felt that its alpha clue, written by Chris Locke, still wasn’t true. It said,

we are not seats or eyeballs or end users or consumers.

we are human beings and our reach exceeds your grasp. deal with it.

There is a theory in there that says the Internet gives human beings (the first person we) the reach they need to exceed the grasp of marketers (the second person your).

So either the theory wasn’t true, or the Internet was a necessary but insufficient condition for the theory to prove out. I went with the latter and decided to to work on the missing stuff.

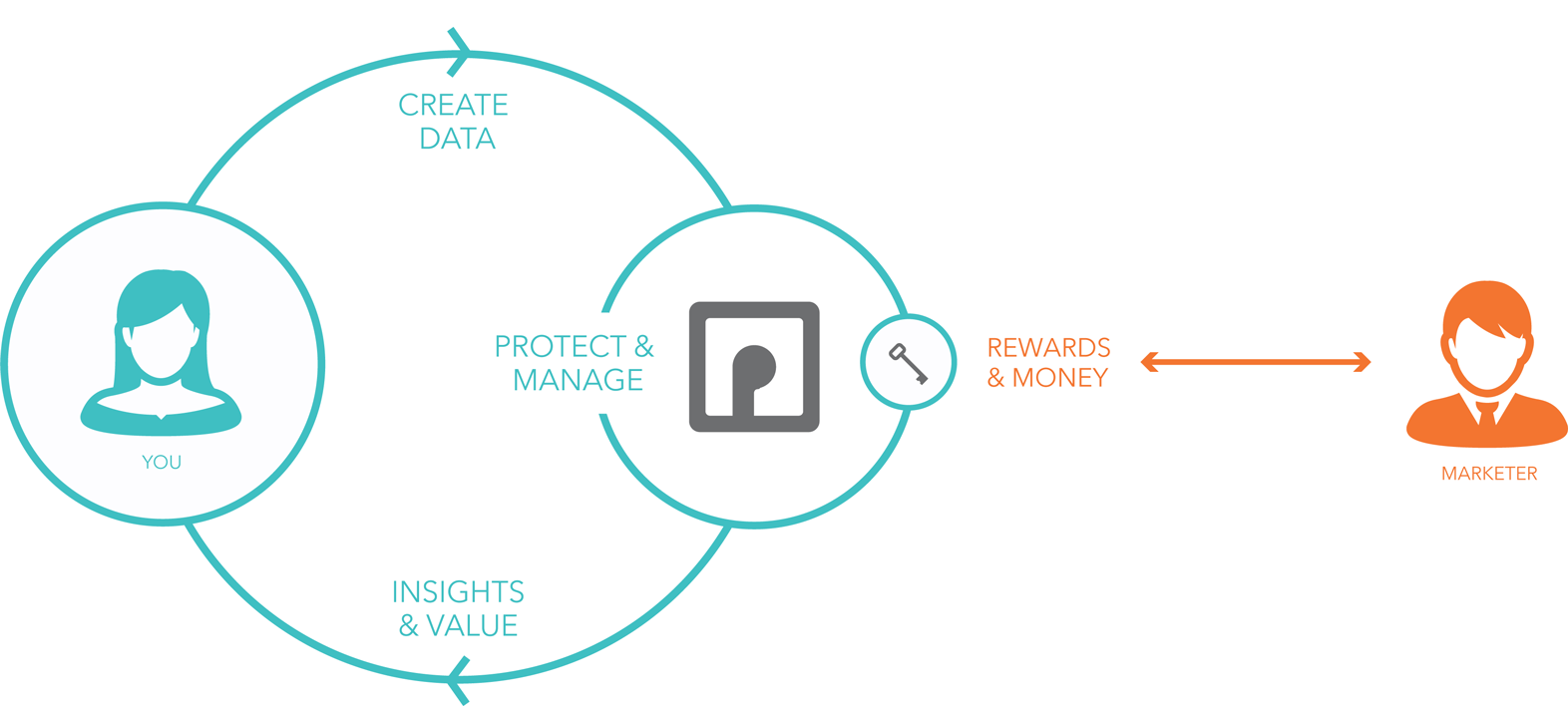

That stuff couldn’t come from marketers, because they were on the second person side. In legal terms, they were the second party, not the first. This is why their embrace of Cluetrain’s “markets are conversations” couldn’t do the job. Demand needed help that Supply couldn’t provide. What we needed, as individuals, were first party solutions — ones that worked for us.

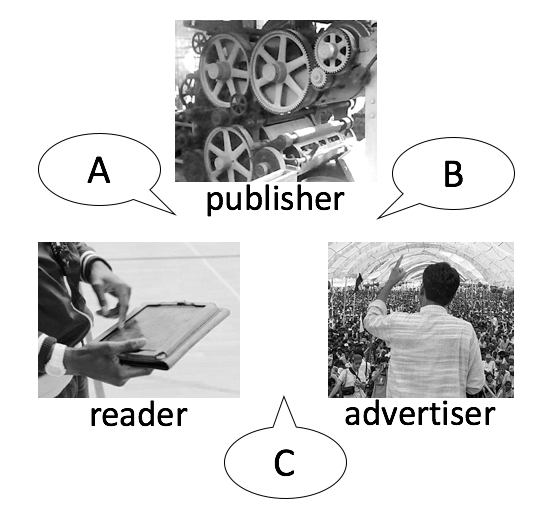

The more I thought about the absence of first party solutions, the more I realized that this was a huge hole in the marketplace: one that was hard to see from the client-server perspective, always drawn like this:

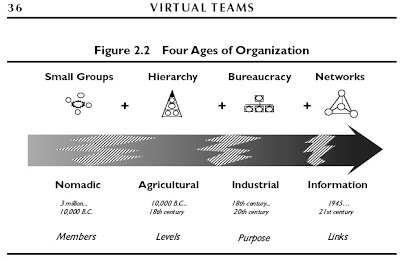

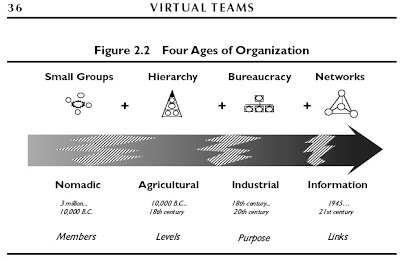

While handy and normative, client-server is also retro. Here’s a graphic from Virtual Teams: People Working Across Boundaries with Technology (Jessical Lipnack and Jeffrey Stamps, 2000, p. 47) that puts it in perspective:

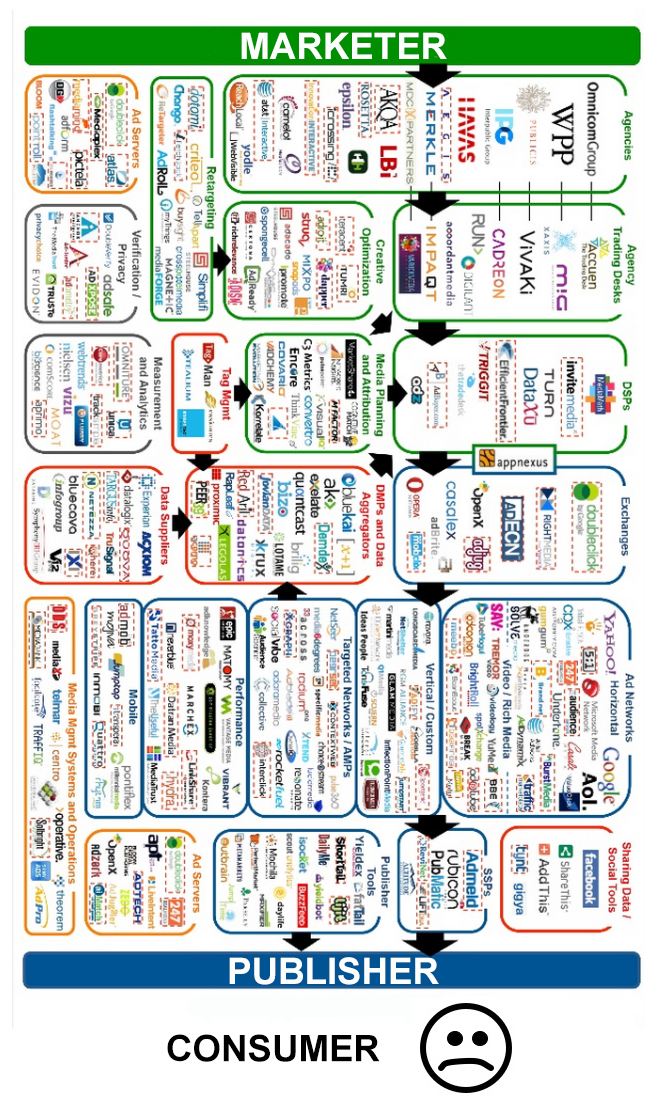

Client-server is hierarchical, bureaucratic industrial and agricultural (see the image below). But it’s also most of what we experience on the Web, and also where the entirety of the supply side sits. So, even if Cluetrain is right when it says (in Thesis #7) “hyperlinks subvert hierarchy,” subversion goes slow when the people running the servers are in near-absolute control and hardly care at all about links. In less abstract terms, what we have on the Web is this:

As clients we go to servers for the milk of text, graphics, sound and videos. We get all those, plus cookies (and other tracking methods) to remember who we are and where we were the last time we showed up. And, since we’re just clients, and servers do all the heavy lifting (and with technology what can be done will be done) the commercial Web’s ranch has turned into what Bruce Schneier calls Our Internet surveillance state.

By 2006 it was already clear to me that we could make the whole marketplace a lot bigger if individuals were fully capable human beings and not just calves — if we equipped Demand to drive Supply at least as well as Supply drives Demand.

To help people imagine what will happen when Demand reaches full power, I wrote a Linux Journal column a few months earlier, titled “The Intention Economy.” Here’s the gist of it:

The Intention Economy grows around buyers, not sellers. It leverages the simple fact that buyers are the first source of money, and that they come ready-made. You don’t need advertising to make them.

The Intention Economy is about markets, not marketing. You don’t need marketing to make Intention Markets.

The Intention Economy is built around truly open markets, not a collection of silos. In The Intention Economy, customers don’t have to fly from silo to silo, like a bees from flower to flower, collecting deal info (and unavoidable hype) like so much pollen. In The Intention Economy, the buyer notifies the market of the intent to buy, and sellers compete for the buyer’s purchase. Simple as that.

The Intention Economy is built around more than transactions. Conversations matter. So do relationships. So do reputation, authority and respect. Those virtues, however, are earned by sellers (as well as buyers) and not just “branded” by sellers on the minds of buyers like the symbols of ranchers burned on the hides of cattle.

The Intention Economy is about buyers finding sellers, not sellers finding (or “capturing”) buyers.

In The Intention Economy, a car rental customer should be able to say to the car rental market, “I’ll be skiing in Park City from March 20-25. I want to rent a 4-wheel drive SUV. I belong to Avis Wizard, Budget FastBreak and Hertz 1 Club. I don’t want to pay up front for gas or get any insurance. What can any of you companies do for me?” — and have the sellers compete for the buyer’s business.

This car rental use case is one I’ve used to illustrate what would be made possible by “user-centric” or “independent” identity, which was also the subject of the cover story in last October’s Linux Journal, plus this piece a year earlier, and various keynotes I’ve given at Digital Identity World, going back to 2002. It is also the use case against which the new open source Higgins project was framed.

Even though I’ve been thinking out loud about Independent Identity for years, I didn’t have a one-word adjective for the kind of market economy it would yield, or where it would thrive. Now, thanks to all the unclear talk at eTech about attention, intentional is that adjective, because intent is the noun that matters most in any economy that gives full respect to what only customers can do, which is buy.

Like so many other things that I write about (including everything I’ve written about identity), The Intention Economy is a provisional idea. It’s an observation that might have no traction at all. Or, it might be a snowball: an core idea with enough heft to roll, and with enough adhesion to grow, so others add their own thoughts and ideas to it.

So that’s the purpose I chose for my new Berkman project: to get a snowball of development rolling toward the Intention Economy.

The project has been lightweight from the start, consisting of myself* and other volunteers. Our instruments are this blog, a wiki, a mailing list and events. In gatherings of project volunteers at Berkman and elsewhere, we narrowed our focus to encouraging development of tools for independence and engagement. That is, tools that would make individuals both independent of other entities (especially companies) and better able to engage with them. These shaped the principles, goals and tools listed on our wiki.

The term VRM came about accidentally. I was talking about my still-nameless project on a Gillmor Gang podcast in October 2006. Another guest on the show, Mike Vizard, started using the term VRM, for Vendor Relationship Management — or the customer-side counterpart of CRM, for Customer Relationship Management, which was then about a $6.2 billion B2B software and services industry. (It’s now past $20 billion.) The Gillmor Gang is a popular show, and the term stuck. It wasn’t perfect (we wanted a broader focus than “vendors,” which is also a B2B term, rather than C2B). But the market made a decision and we ran with it. Since then VRM has gained a broader meaning anyway. Every thing (hardware, software, policies, legal moves) that enables an individual to interact with full agency in any relationship is a VRM thing. “RM” turns out to be handy for sub-categories as well, such as GRM (government relationship management) and HRM (health relationship management).

ProjectVRM has always been unusual for Berkman in two ways. One is that it has been focused on business — the commercial side of the “society” in Berkman’s name. The other is that it put the development horse ahead of the research cart. So, while we always wanted to do research (and did some along the way, such as with ListenLog), we felt it was important to create research-worthy effects first.

My first mistake was thinking we would have those effects within a year. My second mistake was thinking we would have them within four years — the length of my fellowship. It has taken twice that long, and still requires one more piece. More about that below, in the Research and Opportunities sections.

In its early years, when it was pure pioneering, ProjectVRM had a lot of volunteer organizational help. There were weekly conference calls and meetings, and events held in Cambridge, London, San Francisco and elsewhere. But the main gatherings from the start were at the Internet Identity Workshop (IIW), an unconference I co-organize at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View. (Our next VRM Day is 27 October. Register here.)

IIW also started with Berkman help. It was first convened as a group I pulled together for a December 31, 2004 Gillmor Gang podcast on identity. Steve Gillmor called the nine participants in the show “The Identity Gang.” The conversation continued by phone and email, with growing energy. So we convened again, this time in person with a larger group, in February 2005 at Esther Dyson’s PC Forum in Scottsdale, Arizona. It was there that John Clippinger asked if we would like “a clubhouse” at Berkman. I said yes, and John had Paul Trevithick create a Berkman site for the gang. As interest collected around the site and its list, three members — Phil Windley (then CIO of Utah), Kaliya Hamlin (aka “IdentityWoman“) and I morphed the gang meetings into IIW, which met for the first time in Fall of 2005. Our 19th is coming up on 28-30 October. (Register here.) It tends to have 180-250 participants from all over the world. While identity remains the central theme, as an unconference its topics can be whatever participants choose. VRM is always a main focus, however. And we always have a “VRM Day” at the Museum the day before IIW. The next is on 27 October. It’s free.

The Identity Gang also grew out of other efforts by a number of individuals and groups:

- Digital ID World, a yearly conference started in 2002 by Andre Durand and Phil Becker, and organized by Eric Norlin. I gave the closing keynotes for most of them.

- Identity Commons, which started in 2001. Kaliya Hamlin, Owen Davis and Drummond Reed were all active in it. Kaliya, aka IdentityWoman, introduced me to it in the summer of 2004.

- The Social Physics Project and Eclipse/Higgins (an open source project led by Paul Trevithick and Mary Ruddy), which John Clippinger tied in with the Berkman Center (as he did me as well). John unpacks this a bit in his book A Crowd of One. (SocialPhysics.org is now an MIT Media Lab thing, and the subject of a new Sandy Pentland book by the same name. John is also at the Media Lab now.)

- The Open Identity Exchange (OIX).

- The Information Card Foundation, which grew out of Microsoft’s work on Identity, building especially on Kim Cameron’s thinking and architecture.

I’ll leave it at those for now. Others can add to it and help me connect the dots later. What matters is that ProjectVRM has both roots and branches that intertwine with the digital identity movement. I unpack more in the Community section below. Meanwhile it is essential to note that Kim Cameron’s Seven Laws of Identity had a large guiding influence on ProjectVRM. This is partly because they were all good laws, but mostly because they came from the individual’s side:

- User control and consent

- Minimal disclosure for a constrained use

- Justifiable parties (“disclosure of identifying information is limited to parties having a necessary and justifiable place in a given identity relationship”)

- Directed identity (“facilitating discovery while preventing unnecessary release of correlation handles”)

- Pluralism of operators and technologies

- Human integration

- Consistent experience across contexts

As you see, all of those should apply just as well to VRM tools and services.

We have had two interns in our history, both hugely helpful. The first was Doug Kochelek, an HLS law student with a BS and a EE from Rice. He came on board at the very beginning, in September 2006. He’s the guy who worked with Berkman’s Geek Cave to create the wiki, the blog and the list. He also shook down many technical problems along the way. The second was Alan Gregory, a 2009 summer intern and a law student at the University of Florida. Alan helped with research on the chilling effects of copyright expansion on Web streaming, which was a focus of a research project we did with PRX called ListenLog — a self-tracking feature installed in PRX’s Public Media Player iPhone app. (Here’s a presentation Alan and I did at a Fellows Hour.) ListenLog was the brainchild of Keith Hopper, then of NPR, and was years ahead of its time. Work on those projects was funded by a grant from the Surdna Foundation.

To keep its weight light and its work focused on development and relevant issues, ProjectVRM does not have its own presence on Twitter or Facebook. Its social media activity is instead comprised of postings by individual participants in the project, and the memes they drive. #VRM, for example, gets tweeted plenty, and has come to serve as shorthand for individual empowerment.

In 2007 we did a good job of publicizing what VRM and ProjectVRM were about, and got a lot of buzz. It was premature, and our first big lesson: it’s not good to publicize anything for which the code isn’t ready. In the absence of code, it’s easy for commentators (such as here) to assume that what we’re trying to do can’t be done.

So we got more heads-down after that, and avoided publicity for its own sake.

Still, the idea of VRM is attractive, especially to folks at the leading edge of CRM. This is what caused nearly an entire issue of CRM magazine to be devoted to VRM ,in May 2010. It too was ahead of its time, but it helped. So did two books that came out the same year: John Hagel’s The Power of Pull, and David Siegel’s Pull: The Power of the Semantic Web to Transform Your Business. John also helped in June 2012 with The Rise of Vendor Relationship Management.

Still, the idea of VRM is attractive, especially to folks at the leading edge of CRM. This is what caused nearly an entire issue of CRM magazine to be devoted to VRM ,in May 2010. It too was ahead of its time, but it helped. So did two books that came out the same year: John Hagel’s The Power of Pull, and David Siegel’s Pull: The Power of the Semantic Web to Transform Your Business. John also helped in June 2012 with The Rise of Vendor Relationship Management.

That essay was a review of The Intention Economy: When Customers Take Charge, which arrived in May from Harvard Business Review Press. The book reported on VRM development progress and detailed the projected shifts in market power that I first called for in my 2006 column with the same title.

While The Cluetrain Manifesto has been a bigger seller, The Intention Economy  has had plenty of effects. Currently, for example, it is informing the work of Mozilla’s commercial arm, headed by Darren Herman, who this year hired @SeanBohan from the VRM talent pool. (Here’s a talk I gave at Mozilla in New York last month.) On the publicity side, the book was compressed to a Wall Street Journal full-page Review section cover essay titled “The Customer as a God.”

has had plenty of effects. Currently, for example, it is informing the work of Mozilla’s commercial arm, headed by Darren Herman, who this year hired @SeanBohan from the VRM talent pool. (Here’s a talk I gave at Mozilla in New York last month.) On the publicity side, the book was compressed to a Wall Street Journal full-page Review section cover essay titled “The Customer as a God.”

So far ProjectVRM has one spin-off: Customer Commons, a California-based nonprofit. Its mission is “restore the balance of power, respect and trust between individuals and organizations that serve them.” CuCo is a membership organization with the immodest ambition of attracting “the 100%.” In other words, all customers. And it is modeled to some degree on Creative Commons  (a successful early Berkman spin-off), by serving as the neutral place where machine- and person-readable versions of personal terms, conditions, policies and preferences of the individual can be maintained. Among those terms will be those restricting or preventing unwanted tracking, and among those policies will be those establishing the boundaries we call privacy. Customer Commons is a client of the Cyberlaw Clinic, which is helping develop both. But much more can be done. We’ll visit that in the Opportunities section below.

(a successful early Berkman spin-off), by serving as the neutral place where machine- and person-readable versions of personal terms, conditions, policies and preferences of the individual can be maintained. Among those terms will be those restricting or preventing unwanted tracking, and among those policies will be those establishing the boundaries we call privacy. Customer Commons is a client of the Cyberlaw Clinic, which is helping develop both. But much more can be done. We’ll visit that in the Opportunities section below.

2. Development

The list of VRM developers is now up to many dozens. While most don’t use the term “VRM” in marketing their offerings (nor do we push it), the term is gathering steam. For example, while updating the developers list a few minutes ago, I found two new companies that use VRM in the description of their offerings: InformationAnswers (“Where CRM meets VRM.”) and PeerCraft (“The main purpose for PeerCraft is to support Vendor Relation Management.”)

Some developers on our list are now familiar brands, though none started that way, and most did not exist when ProjectVRM began. Some of the successes (e.g. Uber and Lyft) have not been directly engaged with ProjectVRM, but are listed because they are what we call “VRooMy.” Other successes (e.g. Personal.com, Reputation.com and GetSatisfaction) have been engaged, one way or another. One that got a lot of notice lately is Thumbtack, for picking up a $100 million investment from Google. That’s atop the $30 million they got earlier this year.

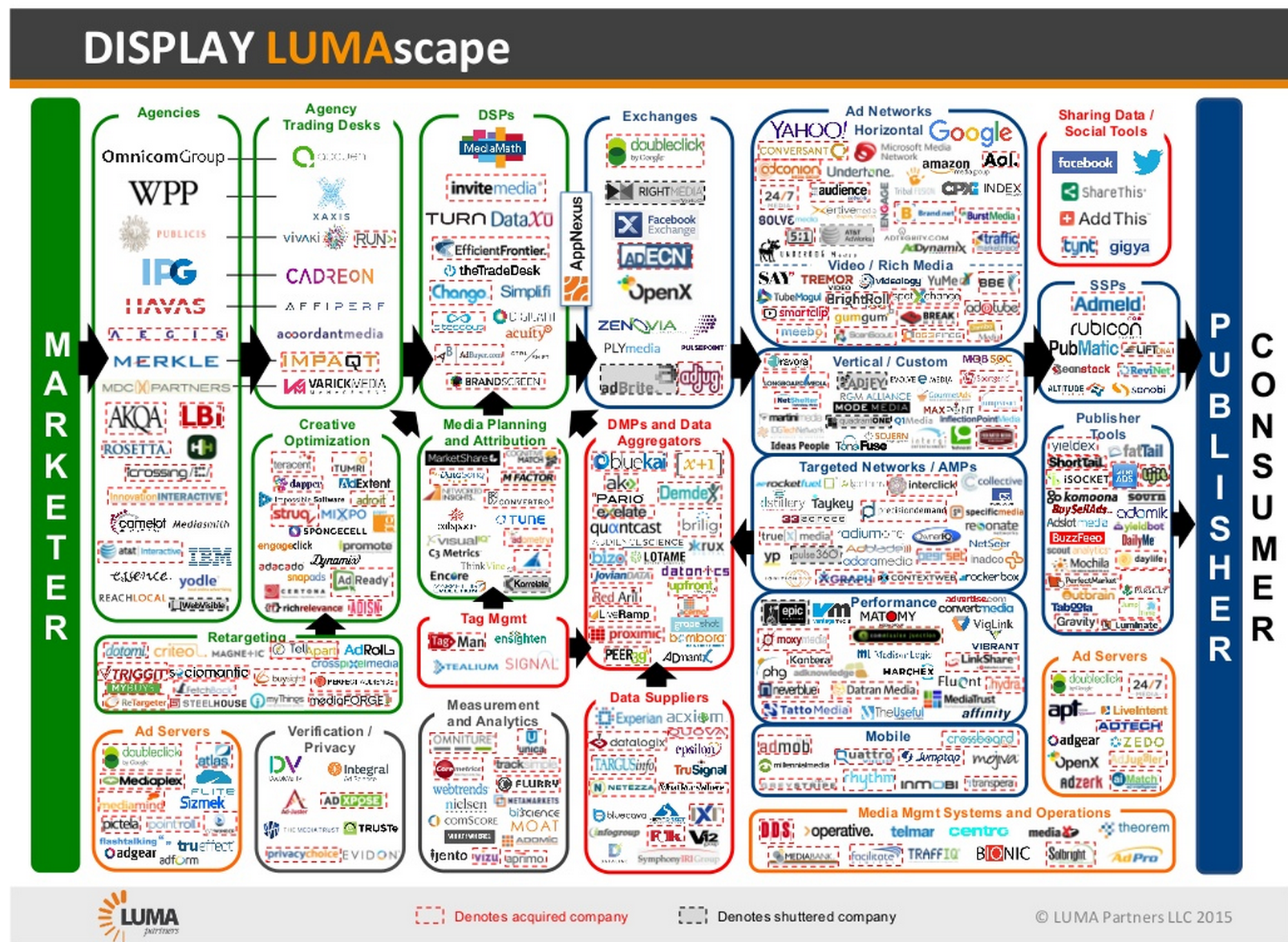

In fact many VRM developers are now having an easier time getting money, thanks to a trend on which ProjectVRM has had influence: a shift of market interest away from “push” (e.g. advertising) and toward “pull” (e.g. VRM). (More about investment below.)

Several years ago, a bunch of VRM developers (and I) worked on developing SWIFT’s Digital Asset Grid. (SWIFT is the main international system for moving money around, and is headquartered in Belgium.) The code is open source, as is other VRooMy work in the financial sector. (Such as the stuff being done by the Romanian company I wrote about here.) OIX also maintains a set of “trust frameworks,” one of which is at the heart of the Respect Network, which I’ll unpack below.

While there is a lot of development in the U.S., and there are VRM startups scattered around the world, the three main hotbeds of activity are the UK, France and Oceania (Australia and New Zealand). Each is a community of its own, cohering in different ways. It’s helpful to visit each, because they represent unique contexts and resources for moving forward.

The UK

In the UK, government is central, through a role one official there calls “being a giant consumer of personal data from citizens.” It gets that data either from individuals directly or from companies that provide individuals with what are called variously called personal clouds, data stores, lockers and vaults. While all these companies perform as intermediaries, they work primarily for the individual. To differentiate this new class of company from traditional third parties, ProjectVRM calls them “fourth parties”. (That term is alien to lawyers, but is catching on anyway. For example, there is a new VRM company in Australia with the name “4th Party.”)

Leading the UK government in a VRooMy direction from the inside is in the Efficiency and Reform Group of the Government Digital Service (GDS) in the Cabinet Office. In this presentation by Chris Ferguson, Deputy Director of the GDS we see the government pulling in big companies (e.g. Google, Equifax, Lexis-Nexis, Experian, Paypal, Royal Mail, BT, Amazon, O2, Symantec) to legitimize and engage fourth parties serving individuals (e.g. Mydex, Paoga and Allfiled).

Two outside groups working with the UK government are Ctrl-Shift and OIX (Open Identity Exchange). Ctrl-Shift is a research consultancy that has been engaged with ProjectVRM from the beginning. OIX is a Washington-based international .org focused on ‘building trust in online transactions.’

France

VRM is a familiar and well-understood concept in France. There are meetups (such as this one) and many VRooMy startups, such as Privowny (led by French folk and HQ’d in Palo Alto), CozyCloud, and OneCub. A big organizational driver of VRM in France is Fing.org, a think tank that brings together large companies (e.g. Carrefour, Societe General, Orange and LaPoste) with small companies such as the ones I just mentioned. They do this around research projects. For example, ProjectVRM informed Fing’s Mesinfos research project (described here).

Oceania

If we were to produce a heat map of VRM activity, perhaps the brightest area would be Australia and New Zealand. I’ve been down that way three times since June of last year, to help developers and participate in meetings and events. As with the UK, government in Australia is very supportive of VRM development, and with empowering individuals generally. (We met with three agencies on one of the trips: one with the federal government in Canberra and two with the New South Wales government in Sydney. One of them called citizens “customers” of government services, because “they pay for them.”) Startups there include Flamingo, Meeco, Welcomer, Geddup,4th Party, Fifth Quadrant, Onexus and the New Zealand based MyWave.

Recent changes in Australian privacy policy also attract and support VRM development. Australian companies (and government agencies) collecting personal data from people on the Web (or anywhere) are now required to make that data available to those people to use as they please. (Or so I understand it.) This gives Canberra-based Welcomer, for example, a reason to exist. Welcomer makes “private data dashboards” that “show collected summaries of the personal data held by organisations and by individuals including the person themselves. The dashboard gives a summary of personal data with the ability to link through to the source data (where required).”

This summer, the first commercial community to grow out of ProjectVRM work, the Respect Network (which Privacy By Design (PbD) calls the “World’s First Global Private Cloud Network”) held a world tour to launch the community and stimulate funding for members’ common goals, standards and code development. I was on the tour (London, San Francisco, Sydney, Tel Aviv), and wrote a report on the ProjectVRM blog. (Naturally, I shot pictures. Those are here. I also spoke at each venue. One of my Sydney talks is here.)

3. Community

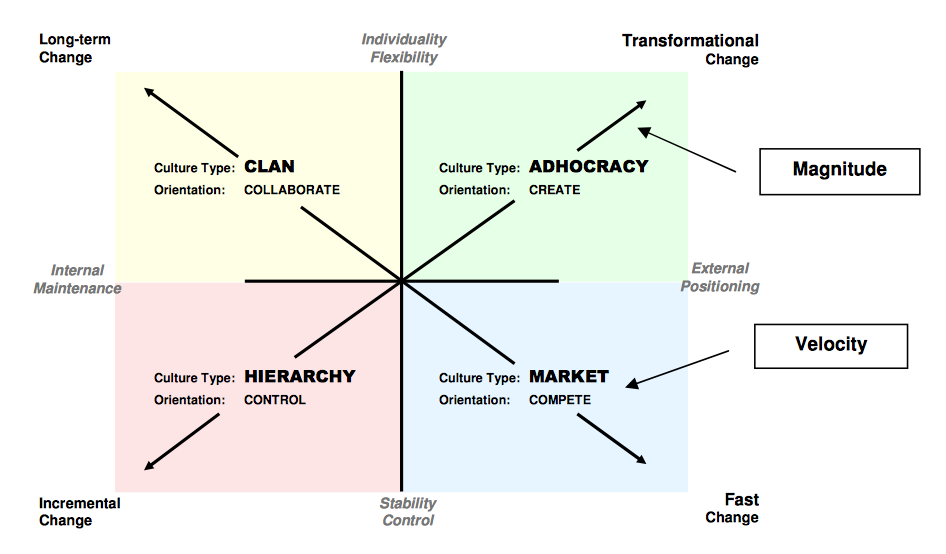

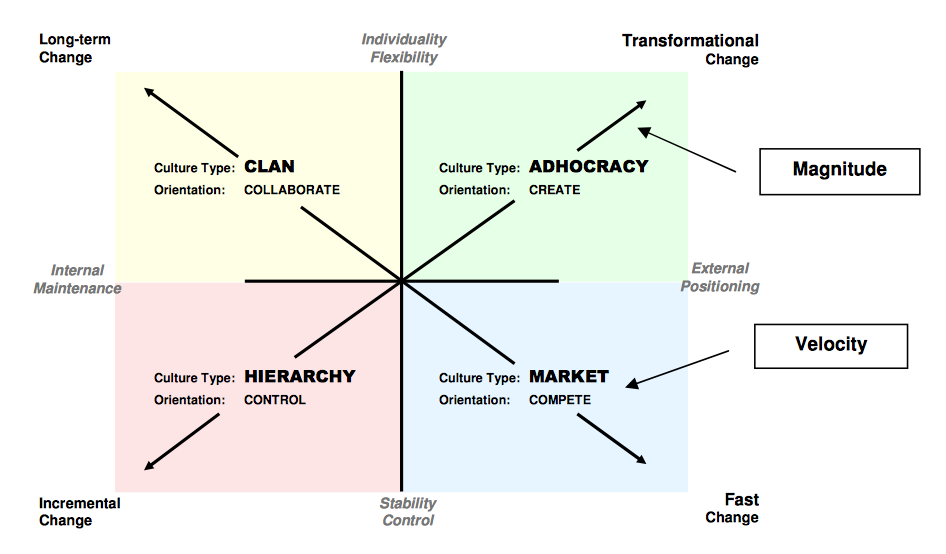

To understand where ProjectVRM fits in the world, and how it works, I like the Competing Values Framework by Kim S. Cameron (no relation to the one above), Robert E. Quinn, Jeff DeGraff and Anjan Thakor:

While there are many VRM developers operating in the lower half of that graphic, what ProjectVRM does is in the upper half of that diagram. We have a collaborative clan of flexible and creative individuals in an adhocracy, working together on long-term transformational change.

Pretty much everything that gets criticized about our efforts falls in the lower half. That’s because we have no hierarchy and don’t work to control what anybody does. And progress on the whole has been slow. (Though there are exceptions, such as Uber, Lyft and Thumbtack.)

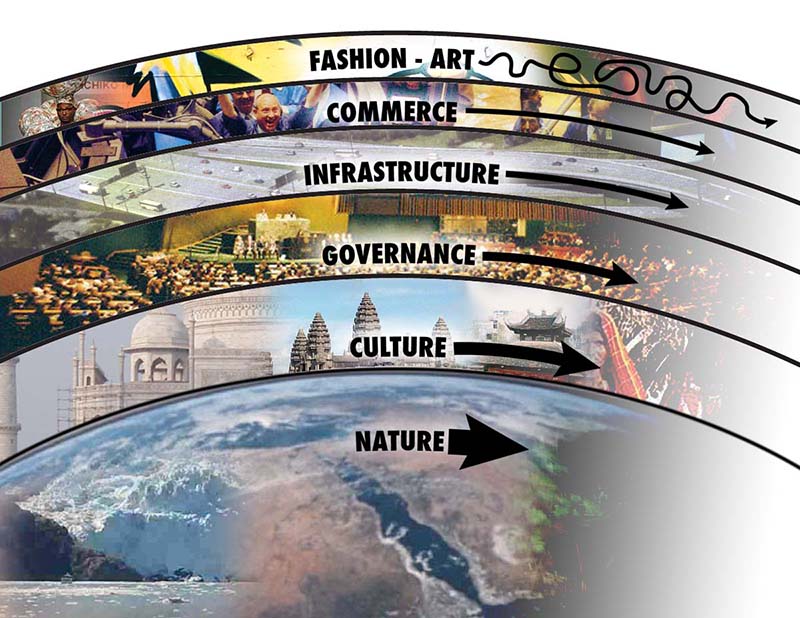

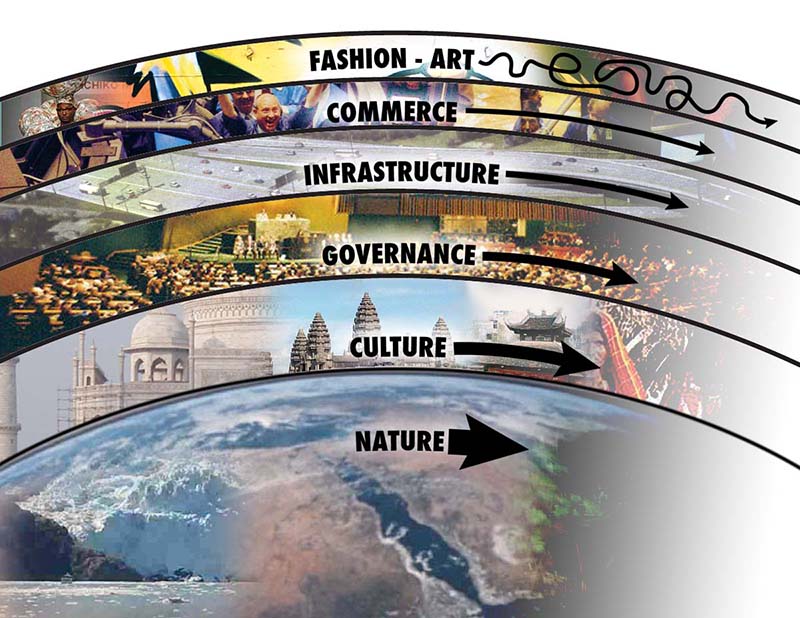

That graphic is just one of many helpful ones in David Ronfeldt‘s Organizational forms compared, which he’s been updating since first publishing it in May 2009. One reason it is helpful is that the hierarchical short-term stuff is obvious and easily understood, while collaborative long term stuff is much harder to grok. It’s like the difference between weather and geology. Which makes me think that graphic should be flipped vertically: slow stuff on the bottom, fast stuff at the top. That’s what the Long Now foundation does with this graphic, which I’ve always loved:

The change we want most is down in the culture, governance and infrastructure layers, even though our focus is on commerce. This also explains why we run into trouble when we play with fashion. The last thing we want is for VRM to be cool. (This is also a lesson I learned and re-learned over two decades of watching Linux, free software and open source for Linux Journal.)

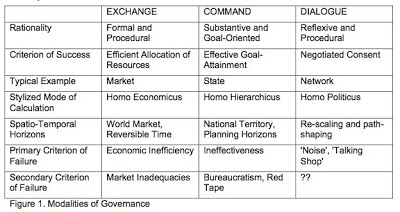

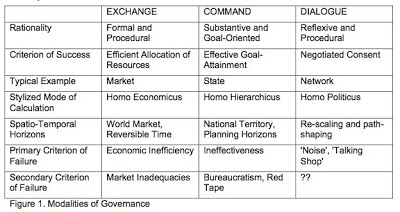

The following graphics are all from David Ronfeldt’s scholastic gatherings. Each in its own way helps explain how our community works — and how it doesn’t. First, from one of Bob Jessop‘s many papers on governance and metagovernance (this one from 2003):

That’s our column on the right.

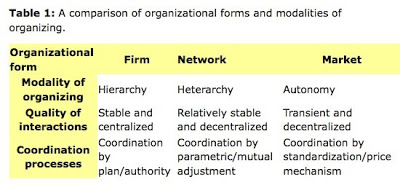

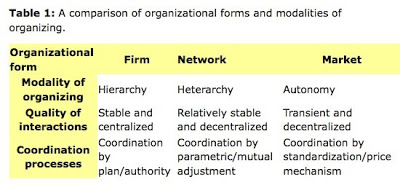

Then there is this, from Federico Iannacci and Eve Mitleton–Kelly’s Beyond markets and firms: the emergence of Open Source networks (First Monday, May, 2005):

That’s us in the middle. We’re a stable and decentralized heterarchy that coordinates by mutual adjustment.

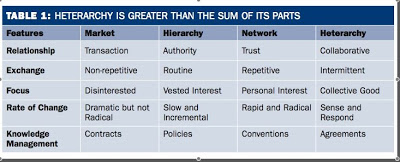

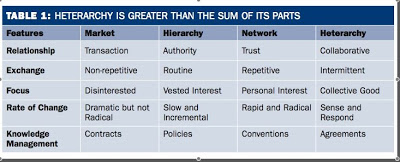

Then there is this from Karen Stephenson‘s Neither Hierarchy nor Network: An Argument for Heterarchy (in Ross Dawson’s Trends in the Living Networks, April, 2009):

Again that’s us on the right.

Something I like about those last two is the respect they give to heterarchy, which has been a focus for many years of Adriana Lukas, another VRM stalwart who has been with the project since before the beginning. Here’s her TED talk on the subject.

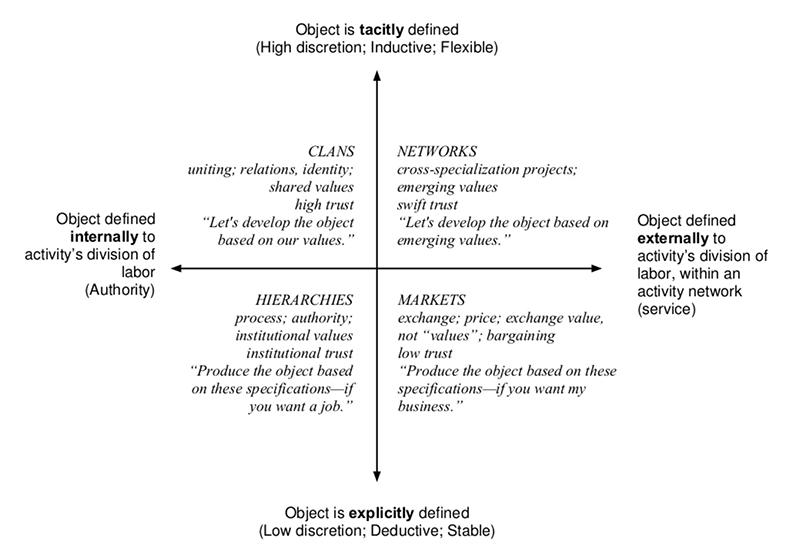

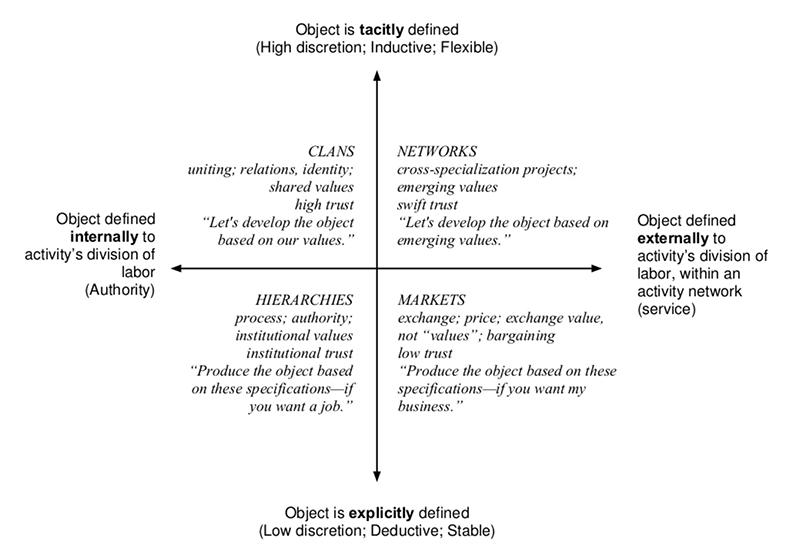

Finally, there is this graphic, from Clay Spinuzzi‘s Toward a Typology of Activities (2013):

In Spinuzzi’s Losing by Expanding: Corralling the Runaway Object, an object is identified as “a material or problem that is cyclically transformed by collective activity.” With our tacit, inductive and flexible approach, this also characterizes the way our community works.

One can see all this at work on the ProjectVRM mailing list, an active collection of 615 subscribers. We also meet in person twice a year at IIW, starting one day in advance of the event, with “VRM Day.” This adds up to a total of at least eight days per year of in-person collaboration time.

Most of the rest of the VRM community meets locally, or through the organizing work of organizations such as Respect Network (U.S. based, but spanning the world) and Fifth Quadrant (Sydney based, and focused on Australia and New Zealand).

There are many other organizations with which ProjectVRM is well aligned. Among them are:

If things go the way I expect, Mozilla will also emerge as a center of VRM interest and development as well. (For example, I expect VRM to be a topic in October at MozFestival in the U.K.

4. Influence

Nearly all VRM influence derives from the work of its volunteers and its developers. “Markets are conversations,” Cluetrain said, and we drive a lot of those. But they rarely get driven exactly the way I, or we, would like. Conversations are like that.  So are heterarchical networks. Everybody wants to come at issues from their own angle, and often with their own vocabulary. We see that especially with analysts and think tanks. None of them like the term VRM. (In fact lots of developers avoid it as well. I don’t blame them, but we’re stuck with it.) Ctrl-Shift, for example, calls fourth parties PIMS, for Personal Information Management Services. Kuppinger-Cole, which gave ProjectVRM an award in 2008 (that’s the trophy on the right), insists on the term “Life Management Platforms.” (I pushed it for awhile. Didn’t take.) Here in the U.S., Forrester Research calls the same category PIDM for Personal Identity and Data Management. We don’t care, because we look for effects.

So are heterarchical networks. Everybody wants to come at issues from their own angle, and often with their own vocabulary. We see that especially with analysts and think tanks. None of them like the term VRM. (In fact lots of developers avoid it as well. I don’t blame them, but we’re stuck with it.) Ctrl-Shift, for example, calls fourth parties PIMS, for Personal Information Management Services. Kuppinger-Cole, which gave ProjectVRM an award in 2008 (that’s the trophy on the right), insists on the term “Life Management Platforms.” (I pushed it for awhile. Didn’t take.) Here in the U.S., Forrester Research calls the same category PIDM for Personal Identity and Data Management. We don’t care, because we look for effects.

As for the influence of others on ProjectVRM, there are too many to list.

5. Issues

Privacy is the biggest one right now. (A Google search brings up more than five billion results). We’ve done a lot to drive interest in the topic, and have brought thought leadership to the topic as well. (Here is one example.) On behalf of ProjectVRM, I’ve participated in many privacy-focused events, such as the Data Privacy Hackathon earlier this year, and at GovLab gatherings such as the one reported on here. I’m also in Helen Nissenbaum‘s Privacy Research Group at the NYU Law School, where I presented ProjectVRM developers’ privacy work on February 26 of this year.

Tied in with privacy online, or lack of it, is users’ need to submit to onerous terms of service and meaningless privacy policies. Those terms, also called contracts of adhesion, have been normative ever since industry won the industrial revolution, but have become especially egregious in the online world. Today there is a crying need both for better terms on the sites’ and services’ side, and for terms individuals can asset on their side. From the beginning ProjectVRM has been focused mostly on the latter.

Trust is another huge issue, also tied with privacy. ProjectVRM has both encouraged and influenced the growth of “trust frameworks” such as the Respect Trust Framework and others (there are five) at OIX, as well as Open Mustard Seed and OpenPDS under IDcubed at the MIT Media Lab.

VRM+CRM has been a focus from the start, but the timing has not been right until now. At the beginning, we expected CRM companies to welcome VRM. Press and analysts in the CRM space were encouraging from the start (CRM Magazine devoted an entire issue to it in 2010), but the big CRM companies showed little interest, until this year.

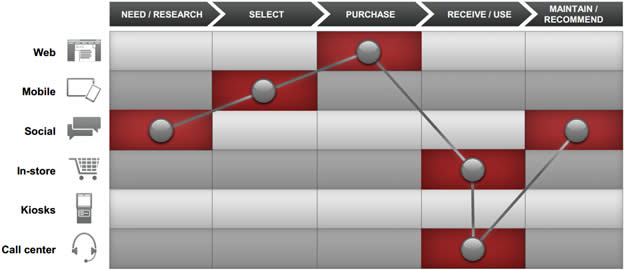

Sitting astride or beside VRM and CRM is a category variously called CX (for Customer Experience), CRX (for Customer Relationship Experience), EM (for Experience Management) CEM or CXM (for Customer Experience Management) and other two and three-letter initialisms. Another happening in the midst of all these is “co-creation” of customer experience. The purpose here is to bring customers and companies together to co-create experience in a lab-like setting where research can be done. This is what Flamingo does in Australia. In a similar way, MyWave in New Zealand (with developers in Australia) “puts the customer in charge of their data and the experience” for a “direct ‘segment of one’ relationship with businesses.”

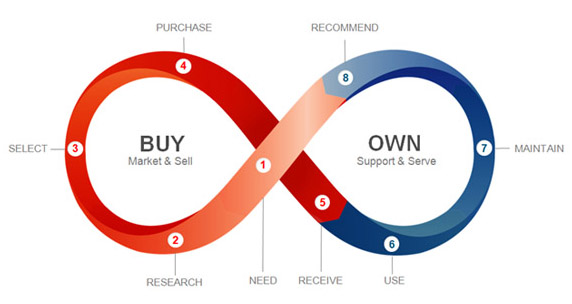

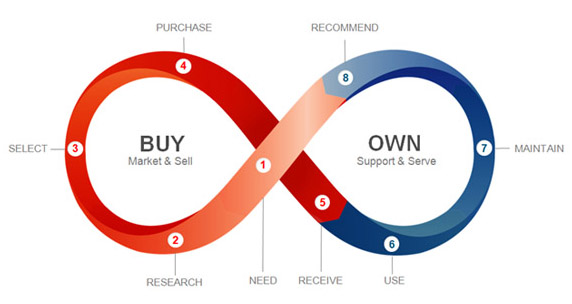

With the Internet of Things (IoT) heating up as a topic, there is also an increased focus, on the “own cycle,” rather than the “buy cycle” of the customer experience. I explain the difference here, using this graphic from Esteban Kolsky:

In our lives the own cycle is in fact the largest, because we own things — lots of them — all the time and are buying things only some of the time. In fact, most of the time we aren’t buying anything, or even close to looking. This is a festering problem with the advertising-driven commercial Web, which assumes that we are constantly in the market for whatever it is they push at us. In addition to not buying stuff all the time, we are employing more and more ways of turning advertising off (ad blockers are the top browser extensions). For advertising and ad-supported companies, including millions of ad-supported publishers on the Web, this is a mounting crisis. According to an August 2013 PageFair report, “up to 30% of web visitors are blocking ads, and that the number of adblocking users is growing at an astonishing 43% per year.” In The Intention Economy, I called online advertising a “bubble” and I stand by the claim. It’s just a matter of time.

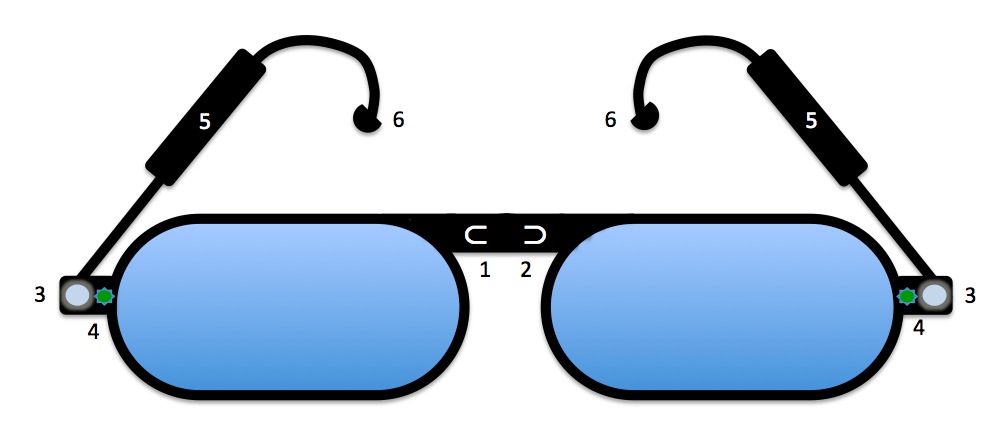

As the stuff we own gets smart, and as more of it finds its way onto the Net service becomes far more important to companies than sales. And VRM developers are laying important groundwork in service. I wrote about this in Linux Journal last year, drawing special attention to the pioneering work led by Phil Windley, who has been a VRM stalwart since before the beginning. In fact it’s Phil’s work that makes clear that things themselves don’t need to be smart to exist on the Internet. All they need is clouds that are smart, which Phil calls picos for persistent computing objects. In this HBR post I explain how the shared clouds of products can be platforms for relationship between company and customers , with learnings flowing in both directions.

Meanwhile, VRooMy companies like trōv are helping individuals do more with what they own — taking their valuables, and making them more valuable.

6. Verticals

Relationship

This was the first for VRM, and it’s still a primary interest. We need tools on the individual’s side for managing many relationships. There still is not a good “relationship dashboard,” though there are a number of efforts in this direction. But as soon as we have code on the VRM side that matches up with code on the CRM side (including, for example, call centers, which are also interested in VRM), we’ll rock.

Payments

Even though ProjectVRM’s mission is centered around relationship and conversation, transaction is a big part of it too — just not the only part, as business often assumes. Our first efforts, starting in 2006, were around making it as easy as possible for individuals to donate money in one standard way to many different public radio stations.

We have been involved in many meetings and discussions around payments and secure data transactions, and some projects as well. We worked with SWIFT on the Digital Asset Grid, and have been in conversations with banks (e.g. Chase) and VISA Europe for a long time as well. With the rise of alternative currencies (e.g. Bitcoin), distributed accounting (e.g. Blockchain), digital wallets and other new means for transacting and accounting, there are many ways for VRM developments to play.

Email

In what is being called “post-Snowden time,” many new secure and encrypted email approaches have evolved. While some are listed on the ProjectVRM developers list, we haven’t been very involved with them — at least not yet. But we are involved with developers working on privacy-protecting tools that can either be embedded in existing email systems or offer alternative communications “tunnels.”

Personal information Management

There are two breeds of development here.

One is fourth party services and code bases for managing and sharing personal data selectively online. There are now many of these. Some support self-hosting as well. (ProjectVRM has always been supportive of free software, open source, and the “first person technology” and “indie” movements.) One organization, the Respect Network, was created to provide a framework for substitutability of services and apps.

The other is code the individual uses to manage his or her own life, and connections out to the world. This is where calendar, email, IM, to-do lists, password managers and other convenience-producing apps for the connected world come together. There is no leader here, though there are many players, including Apple, Microsoft and Google. So far, this area has only seen centralized and siloed players, with inherent security and data mining disadvantages. But recently, commercial and open source conversations about a decentralized approach to this opportunity have been taking place.

A test case for VRM that applies to both kinds of solutions is this: being able to change my address, my last name or my phone number for many services in one move. This is exactly what the UK government is calling for from citizens’ personal information management systems (what Ctrl-Shift calls PIMS). A citizen should be able to change her address for the Royal Mail, the Passport Office and the National Health Service, all at once. Bonus links: Making things open, making things better, by Mike Bracken in the Gov.UK Government Digital Service blog, where Mike’s prior post, Reading the Digital Revolution featured this illustration by our old friend Paul Downey:

Apple’s HealthKit and HomeKit, which go live with the release of iOS 8on 9 September, also have some VRM developers excited, because it will make this kind of integration at the individual end easy to do in two verticals: Health and Home Automation.

Health

Early on with ProjectVRM, I avoided health as an issue, because I wanted to see real progress in my lifetime — and I felt that the situation in the U.S. was fubar. But other VRM folk did not agree, and have pushed VRM forward very aggressively in the health field. Dr. Adrian Gropper and Dr. Deborah Peel of Patient Privacy Rights have done a remarkable job of carrying the VRM flag up a very steep and slippery hill. Berkman veteran John Wilbanks is another active ProjectVRM volunteer whose work in health is broad, deep, influential and at the leading edge of the pioneering space where personal agency engages the wild and broken world of the U.S. health care system. Brian Behlendorf, the primary developer of the Apache Web server (which hosts the largest share of the world’s Web sites and services) and the CONNECT open source code base for health service collaboration, is also an active participant in ProjectVRM.

A number of VRM developers are working with, or paying close attention to, Apple’s HealthKit. In the words of one of those developers, “It’s very VRooMy.” HealthKit developments go live when Apple rolls out iOS 8 on 9 September.

Automotive

While a number of car makers are eager to spy on drivers, Volkswagen has put a stake in the ground. In March, Volkswagen CEO Martin Winkerhorn gave a keynote at the Cebit show that drew this headline: “Das Auto darf nicht zur Datenkrake warden.” My rusty Deutsch tells me he’s saying the car shouldn’t be a data octopus.

Toward that end, Phil Windley’s Kickstarter-based Fuse will give drivers and car owners all the data churned out of their cars’ ODB-II port, which was created originally for diagnostics at car dealers and service stations. With an open API around that data, developers can create apps to alert you to schedule maintenance, monitor your teen’s driving and much more.

Real Estate

The only products that cost us more than cars are homes. Here too we have a VRM advocate in Cambridge-based Bill Wendell of Real Estate Café. He has always been way ahead of his time, but it’s clear his time is coming. (Here’s Bill leading a session on VRM in Real Estate at IIW 18 in May.)

7. Investment

There is an upswing of investment in start-ups on the “pull” — the individual’s — side of the marketplace. Many wealthy individuals, some quite new to tech investing, perceive an opportunity in “pull” side tools, so interest is building, especially in angel funding. There are currently at least three initiatives coming together to invest in VRM or intention based start-ups in Silicon Valley and Europe. This is one of the outcomes of the last IIW (in May of this year), where investment emerged as a big theme, with a number of VC’s for the first time participating in IIW sessions. I’m involved in planning a VRM specific fund, which is still in its preliminary stages. If it moves forward (which I believe it will), it should come into shape by next year.

In some cases government is also involved. In the UK, for example, the SEIS (Seed Enterprise Investment Scheme) program offers huge tax incentives to angel investors.

8. Research

There are many questions we can probe with research, but only one I want to work on in the near term: What happens when individuals come to websites with their own agreeable terms?

Such as, “I’m cool with you tracking me on your site, but don’t follow me when I leave.” And, on the site’s side, “We’re cool with that.” In proper legalese, of course — but expressed on both sides in code and symbols that work like Creative Commons’ licenses (there on the right).

The Cyberlaw Clinic is already involved, though its work with Customer Commons on a broader set of terms than the one I just mentioned, and Berkman’s own Privacy Tools for Sharing Research Data could assist with and follow the process, both through the term-creation process and as the terms get implemented in code and materialize on the Web.

We would be dealing with cooperative efforts that require this already. One is Respect Network’s Respect Connect “Login with Respect” button. As I explain here, the terms of OIX’s Respect Trust frame require the setting of, and respect for, the boundaries of individuals. This can be done, even within the calf-cow framework of client-server.

Respect Connect is based onXDI, which the Respect Trust Framework also specifies. XDI is a protocol that employs “link  contracts.” Drummond Reed, the father of XDI (and CEO of the Respect Network) describes link contracts as “machine-readable XDI descriptions of the permissions an individual is giving to another party for access to and usage of the owner’s personal data.” Very handy. And binding. In code.

contracts.” Drummond Reed, the father of XDI (and CEO of the Respect Network) describes link contracts as “machine-readable XDI descriptions of the permissions an individual is giving to another party for access to and usage of the owner’s personal data.” Very handy. And binding. In code.

Mozilla has also made efforts in this same direction, most recently with Persona (there on the right).  We can help them out with this work, and I am sure other and other browser makers will also want to get on board — which they should, and with Berkman’s convening power probably will.

We can help them out with this work, and I am sure other and other browser makers will also want to get on board — which they should, and with Berkman’s convening power probably will.

At the end of the project we will have both standard terms for posting at Customer Commons and reference implementations hosted by Berkman, or shared by Berkman over Github or some other data repository.

And we would bring to the table many dozens of developers already eager to see increased agency and term-proffering power on the individual’s side. I can easily see privacy dashboards, on both the client and the server sides of websites.

(Thinking out loud here…) We could host focused discussions and invite participants (including law folk — especially students, from anywhere) to vet terms the way the IETF vets Internet standards: with RFCs, or Requests for Comments. Some open source code for this already exists with Adblock Plus’s white list for non-surveillance-based advertisers. I would hope they’d be eager to participate as well. We (ProjectVRM, the Berkman Center or Customer Commons) could publish lists of conformant requirements for website and Web service providers, and lists (or databases) of conformant ones.

This work would also separate respectful actors on the supply side of the marketplace from ones that want to stick with the surveillance model.

While there are lots of things we could do, this is the one I know will have the most leverage in the shortest time, and would be great fun as well.

It is also highly cross-disciplinary, with many lines of cooperation and collaboration within the university and out to the rest of the world. Right at Berkman we have the Privacy Tools for Sharing Research Data project and its many connections to other centers at Harvard. Its mission — “to help enable the collection, analysis, and sharing of personal data for research in social science and other fields while providing privacy for individual subjects” — is up many VRM development alleys, especially around health care.

9. Questions

What if we fail?

What if it turns out that free customers are not more valuable than captive ones for most businesses? That’s been the default belief of big business ever since it was born.

What if the free market on the Net turns out to be “Your choice of captor?” Client-server lends itself to that, although we can work around its inequities with moves like the one proposed in the Research section above.

What if the only VRM implementations that succeed in the marketplace are silo’d and non-substitutable ones? To some degree, that’s what we have with Uber and Lyft. While they are substitutable (as two apps on one phone), we don’t yet have a way to intentcast to multiple ride sharing providers at once, or to keep data that applies to both. Maybe we will in the long run, but so far we don’t.

Apple may be VRooMy with HealthKit and HomeKit, but both still operate within Apples silo. You won’t be able to use them on Android (far as I know, anyway).

And what if the Internet of Things turns out to be a world of silos as well? This too is the default, so far. Phil Windley mocks the Apple of Things and the Google of Things by calling both The Compuserve of Things — and making the case for substitutablility as well.

And what if customers just don’t care? This too is the default: the body at rest that tends to stay at rest. For VRM to fully happen, the whole body needs to be in motion — to move from one Newtonian state to another. It’s doing that in places, but not across the board.

Finally, what if we succeed? VRM is about making a paradigm shift happen. So was Cluetrain before it. On the plus side, the Net itself lays the infrastructural groundwork for that shift. But the rest is up to us.

Whether we fail or succeed (or both), there will be plenty to study. And that’s been the idea from the start too.

_________________

* Disclosures: I was paid modest sums as a fellow early on, but otherwise have received no compensation from the Berkman Center. I make my living as a speaker, writer and consultant. I have consulted a number of companies listed on the ProjectVRM development work page, and am on the boards of two start-ups: Qredo in the U.K. and Flamingo in Australia. In my work for them my main goal is to see VRM succeed, and I don’t play favorites in competition between VRM companies.

Meerkat

Meerkat Periscope

Periscope

Most people reading

Most people reading