CRM — Customer Relationship Management — is a huge business. According to this article, Forrester expected the CRM software market to hit $74 billion in 2007. This more modest Gartner report says the worldwide CRM market totalled $9.15 billion in 2008, growing at a 12.5% rate over 2007.

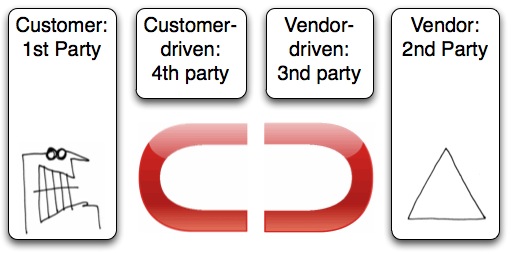

CRM is pure B2B: business to business. You’re not involved, except as a customer of CRM’s customers. It’s your relationship with a company that’s being managed—by the company. Not by you.

Last month Neil Davey of MyCustomer.com reached out from the CRM world to interview me on the subject of VRM. The result is Doc Searls: Customers will use ID data to force CRM change. The angle was data. If VRM gives customers more control over their data and how it is used, how does that help CRM? Wouldn’t customers want to share less of their data rather than more?

In fact data will be front and center as a topic at —

on Monday and Tuesday of next week at Harvard Harvard (please come, it’s free). While most of the workshop will be organized on the open space model (participants choose the topics and break off into groups to move those topics forward), we decided to have one panel, titled Getting Personal With Data: How Users Get Control and What They Do With It. I invite local CRM folks (and everybody interested) to come and participate.

In his piece Neil sourced my new chapter (“Markets are Relationships”) in The Cluetrain Manifesto, as well as text from an interview by email. Since CRM+VRM is our topic here, I thought it would be cool to provide the long form of my answers to Neil’s questions.Here goes…

About what VRM does that CRM alone cannot…

Think of a buyer-seller relationship as vehicle that can be driven by two people: the buyer and the seller. The problem we have today is that only the seller—what in business we call the vendor—can drive. The buyer is in the passenger’s seat. She can’t drive. She can choose to spend or not to spend—or to leave the car and ride with some other vendor. But she can’t drive.

VRM gives her a way to drive.

To mix metaphors a bit, CRM systems are designed to operate what in the tech world we call “silos” or “walled gardens.” It doesn’t matter how nice a company makes its walled garden—it’s still owned and run by the company as a habitat for customers. The company makes all the rules, sets all the terms, provides all the means for everything the customer does with the company. The customer’s only choice is to take the whole deal or leave it.

Every one of CRM’s walled gardens is also different, and most treat the customer as if he or she has no other business relationships, save those to the government or to credit card companies. As a result customers have no common means for relating with multiple vendors. Thus, as CRM system adoption goes up, so do complications for customers.

Perfect example: loyalty programs. Most of these burden the customer with cards and key-ring tags—all to “increase switching costs,” to obtain a higher “share of wallet” or to impose other inconveniences. I know one guy who carries around a key ring with dozens of little tags. In my own case I recently counted fifteen different loyalty cards populating my wallet, my key chains and my glove compartment. None make me feel loyal. All increase my resentment more than “loyalty” by any measure.

Limiting customer choices amounts to wearing blinders. Companies can’t see what they won’t let themselves see. For example, they can’t see customers who choose not to shop at a store because the store only gives discounts and benefits to loyalty card holders. In my own case I buy groceries at Trader Joe’s. rather than Stop & Shop because Trader Joe’s doesn’t require that I carry a loyalty card to get a “discount” that I believe is nothing more than a regular price—while the non-card price amounts to a surcharge and a punishment for non-card-carrying customers. Whether or not this is true, it’s a legitimate perception, and an unintended negative consequence of the loyalty card system. Stop & Shop can put the world’s best data-collection behind its loyalty cards, but one thing they won’t find in that data is why I don’t buy at their store.

Being customer-driven means a company knows what customers actually want and what they actually feel. Wouldn’t it be better to know directly when a customer wants something, rather than to guess at it? Wouldn’t it be better to have whatever market intelligence the customer can provide, willingly, rather than to give the customer a limited set of choices, which may exclude the one thing that might cause a sale or make a better customer?

Friends of mine who have worked in the CRM business, and studied it over many years, tell me that in many — perhaps most — cases, customer-centricity is secondary to organization-centricity. They know of few cases where customers actually drive the company.

In the beginning CRM was about building a “single customer view,” with lots of talk about better understanding the customer’s needs, and how that should be become part of “integrated” marketing, selling and customer service. Over the years, however, this ambition was compromised by minimal data and cost-cutting requirements.

My wife, a business veteran with a long history in retailing (both at the store level and as a supplier) has observed that the trend in recent years has been to out-source support to the customer herself. “Go to our website,” the call center says. Yet typical websites are so poor at customer support that the customer is left to seek help from other customers, or from websites other than the company’s own. This is why so many customers now support each other, rather than bothering with companies’ own support sites and services.

The problem here isn’t bad CRM. It’s that there is nothing yet on the customer’s side to carry some of the relationship weight — other than what CRM systems provide. That means the whole responsibility lies with the vendor. With VRM we want to give the customer means for carrying some of the burden herself.

About VRM and its community…

The current VRM community is a convergence of several formerly separate efforts. In the UK, the Buyer Centric Commerce Forum came together in 2003. In the U.S., VRM grew out of the Internet Identity Workshops, which started in early 2005 — as a workshop discussion subject that broke off and acquired a life of its own. In my own case, VRM started as a sense of unfinished business after Chris Locke, Rick Levine, David Weinberger and I wrote The Cluetrain Manifesto in 1999. Listen to what Chris was saying (in the original manifesto posted at Cluetrain.com) with “we are not seats or eyeballs or end users or consumers. we are human beings and our reach exceeds your grasp. deal with it.” That is the voice of the customer, energized by powers granted by the Internet but not understood by sellers there.

After Cluetrain came out, I realized that Chris’s statement wasn’t quite true, because if customer reach truly did exceed vendor grasp, loyalty cards would be pointless. Customers would have native means for expressing their own wants, needs, terms of engagement and loyalties. Thus I came to realize that relationship was the next frontier. Something had to be done to liberate both sellers and buyers from the belief that a free market is “your choice of captor.”

We didn’t call it VRM, however, until Mike Vizard suggested it during a Gillmor Gang podcast in October 2006. Before that we had called it CoRM (for Company Relationship Management) and other names. As a new fellow at Harvard’s Berkman Center, I needed a project. So I titled mine ProjectVRM, and the rest is history.

On how customers control personal data and its exposure…

The short answer is that customers will disclose data on an as-needed basis, within the context of a secure and genuine relationship, and not a coerced one where the vendor does all the asking.

The longer answer is that this requires a new system on the customer’s part and a modified one on the vendor’s part. That’s how VRM + CRM will work together.

Both systems need to recognize that the individual, and not the organization, should be the point of integration for his or her own data, the point of origination for sharing that data, and the authority about what gets done with that data.

The ‘single customer view’ is naturally that of the customer, not the company. If a working relationship is in place, the customer will share required information when the right time comes — and do it, when need be, for many relationships at once, and in consistent, standardized ways. For example, the customer can issue a trusted change of address just once for many companies, rather than many times and many ways for many companies. In the absence of a customer-driven data-sharing system, we have companies constantly running after the customer for updates and becoming increasingly invasive of privacy over time (Phorm being just one familiar example.)

VRM enables personal data management by the individual, in ways that work for the individual and which can also enable selective disclosure to companies. There are various ways of achieving that, many of which are being actively worked on at present. The plumbing part is easy. Processes and business models are harder, but those are being worked on too.

The challenge lies in developing a more granular view of what data is shared, by whom, how, where and why. For CRM today that equates to WHO, bought WHAT, WHERE, WHEN and HOW it was offered to them. These are all data that can be derived from a system if it is built well enough. These data can then be used to make good guesswork about WHY customers bought products, and then make educated guesses about what customers will buy next.

A well designed VRM system will eliminate much of the the guesswork that CRM currently involves. For example, VRM can provide customers with tools to say “Here’s what I’m in the market for,” or “Here’s my current circumstances. What have you got that is relevant?” — in ways that prevent that data from being used later against the individual, or to inform guesswork that wastes both the vendor’s and the customer’s time and money. The customer also needs to be able to assert his or her own terms of engagement, rather than being forced to accept those required by the vendor. Customer-driven terms would naturally include commitments to pay and otherwise behave honorably; but they might also include preferences (such as “send no junk mail” or “email my receipts”). They might even include expressions of willingness to pay for good service.

On the personal data side, this system will involve what we call “volunteered personal information.” In effect this is a new class of data. Right now that data lives mostly in the heads of customers, because they don’t have the tools or systems to express any of it on their own.

Companies need to be willing to engage with this new type of data. While this may seem scary — giving up control always is — in practice it is just a more highly qualified sales lead and a smoother customer interaction than the current system allows.

On how VRM will influence vendors who don’t want to give up control…

Money talks. Consider one form of VRM we call the Personal RFP. This is where the customer advertises his or her desire to buy a product or service at a given place and time. (And not just through a walled garden such as Facebook or eBay.) For example, “I need a stroller for twins in Grand Rapids in the next 5 hours.” Data with money behind it will fund all kinds of changes in data collection systems.

On other appeals to the CRM side…

A core purpose of VRM is to eliminate the guesswork that has wasted enormous sums of money and energy for marketing and sales — while also wasting the customer’s attention and time. We can save that money, energy and time by giving customers the means to control means of engagement with companies, and to do it in standard ways that work across the board.

It is not possible to see how any of this will work if you look at it only from the supply side of the marketplace — from the standpoint of the seller. You have to take off your seller’s hat and be the other self you’ve always been: a customer.

No customer wants to be “acquired,” “retained,” “managed” or “owned” by any seller. Customers want to be respected on their own terms, and not those of a company that seeks constantly to maintain the advantage in a relationship that actually isn’t.

In other words, they want a real relationship. Not something that is a relationship in name only.

The new dynamic is a green field. We’ve never had it. I believe that if we create the means for enabling good will as well as easy sales, real relationships will follow.

On how “realistic” VRM is…

How realistic was the Internet in 1985?

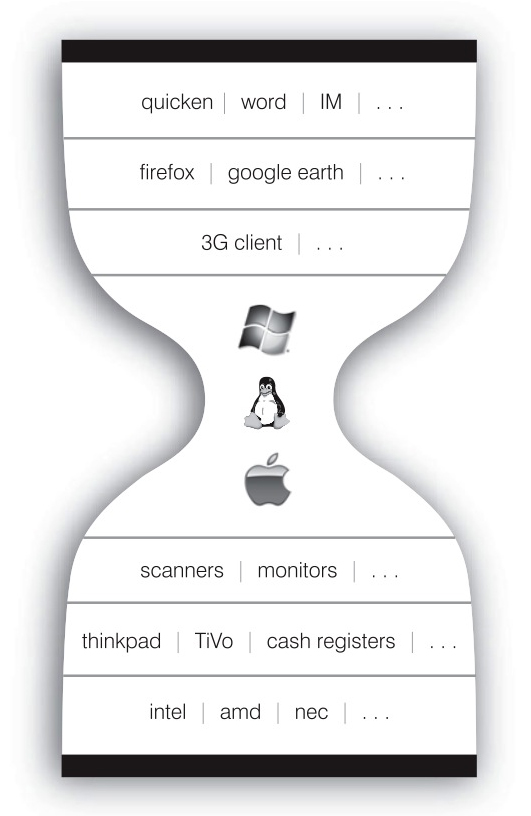

Look at networks in the 80s and early 90s. If you wanted email, or instant messaging, you had to join a walled garden called AOL or Compuserve or Prodigy. If you were an AOL member and wanted to send an email to a Compuserve member, you couldn’t. Just as today you can’t use a Costco loyalty card at a Best Buy.

The Internet changed all that, by providing new protocols for communication that weren’t owned by anybody, but could be used by anybody and improved by anybody.

VRM will likewise change buyer-seller relationships by providing new means for engagement that aren’t owned by anybody, but can be used by anybody and improved by anybody.

Customers are resigned to stuff they hate when they think there are no alternatives. Once the alternatives show up, they will get energized. “Invention is the mother of necessity,” Thorstein Veblen said. What we’re doing with VRM is inventing protocols for buying and selling that will mother many new market necessities. One of those will be reforming CRM so it can respond to real customer demand, along with much better data than was ever before possible.

About where data lives, and how…

Some VRM folks (e.g. Mydex.org) are working on “Personal Data Stores” that can be replicated with trusted “fourth parties“. Some are working on ways of representing personal data (e.g. Azigo.com, Kynetx.com). Some are working on ways of consolidating loyalty data on the customer side and reforming loyalty programs from the outside in (e.g. Scanaroo from Cerado.com). All the many digital identity systems and communities have VRM components and constituents (e.g. Kantara.org, IdentityCommons.org, InformationCard.net, OpenID.org, XDI.org). Some are working on simple customer-held means for organizing one’s own data and relationships (e.g. TheMineProject.org). Some are working on means for logging one’s own media usage, and providing means for putting the pricing gun in customer hands (e.g. ProjectVRM and its friends in various media businesses). Some are working on customer-driven terms of service (e.g. ProjectVRM and friends at Harvard Law School and elsewhere). Some are working on patient control of their own health care data and relationships with health care providers (too many efforts to name, but Google and Microsoft are on this list). Some are working on user driven search, outside the walled gardens of Google and Bing (Switchbook.com). I am probably insulting many by ending the list there, but that should be enough.

About ProjectVRM.org…

ProjectVRM is a research and development project at Harvard’s Berkman Center for Internet & Society. The project was created in 2006, and has focused mostly on development over the following three years. This next year we will be doing much more research as well.

I am a fellow at the center, and I run the project. The vast majority of the development work is going on among members of the VRM community. For them ProjectVRM serves as a central clubhouse, with workshops several times per year, a mailing list, a wiki and other supportive services. The idea isn’t to create a central VRM body, but rather to focus disparate VRM efforts on common goals.

I want to say before closing that we do not mean to give CRM a hard time. The problem CRM has had from the start is that it carries the full burden of systematizing relationships with customers. All VRM does is give customers means for carrying their end of the relationship. We won’t succeed unless it’s VRM + CRM, rather than VRM vs. CRM. If VRM succeeds, it will improve CRM enormously.

a deep and helpful piece by Cliff Gerrish on his Echovar blog. He starts by visiting antagonyms and contranyms (words that carry dual and opposing meanings) and how context tilts perception and meaning toward one side or another. By example he suggests that Google’s problems with Buzz were (at least in part) a result of internal perspective and experience (“Google launched Buzz as a consumer product, but tested it as an enterprise product”). From there he suggests that CRM and VRM also require that we consider perspective and reciprocity:

a deep and helpful piece by Cliff Gerrish on his Echovar blog. He starts by visiting antagonyms and contranyms (words that carry dual and opposing meanings) and how context tilts perception and meaning toward one side or another. By example he suggests that Google’s problems with Buzz were (at least in part) a result of internal perspective and experience (“Google launched Buzz as a consumer product, but tested it as an enterprise product”). From there he suggests that CRM and VRM also require that we consider perspective and reciprocity: