Two new posts with VRM themes just went up.

First, in Linux Journal (@LinuxJournal), How Will the Big Data Craze Play Out?

An excerpt:

I’m wondering when and how the Big Data craze will run out—or if it ever will.

My bet is that it will, for three reasons.

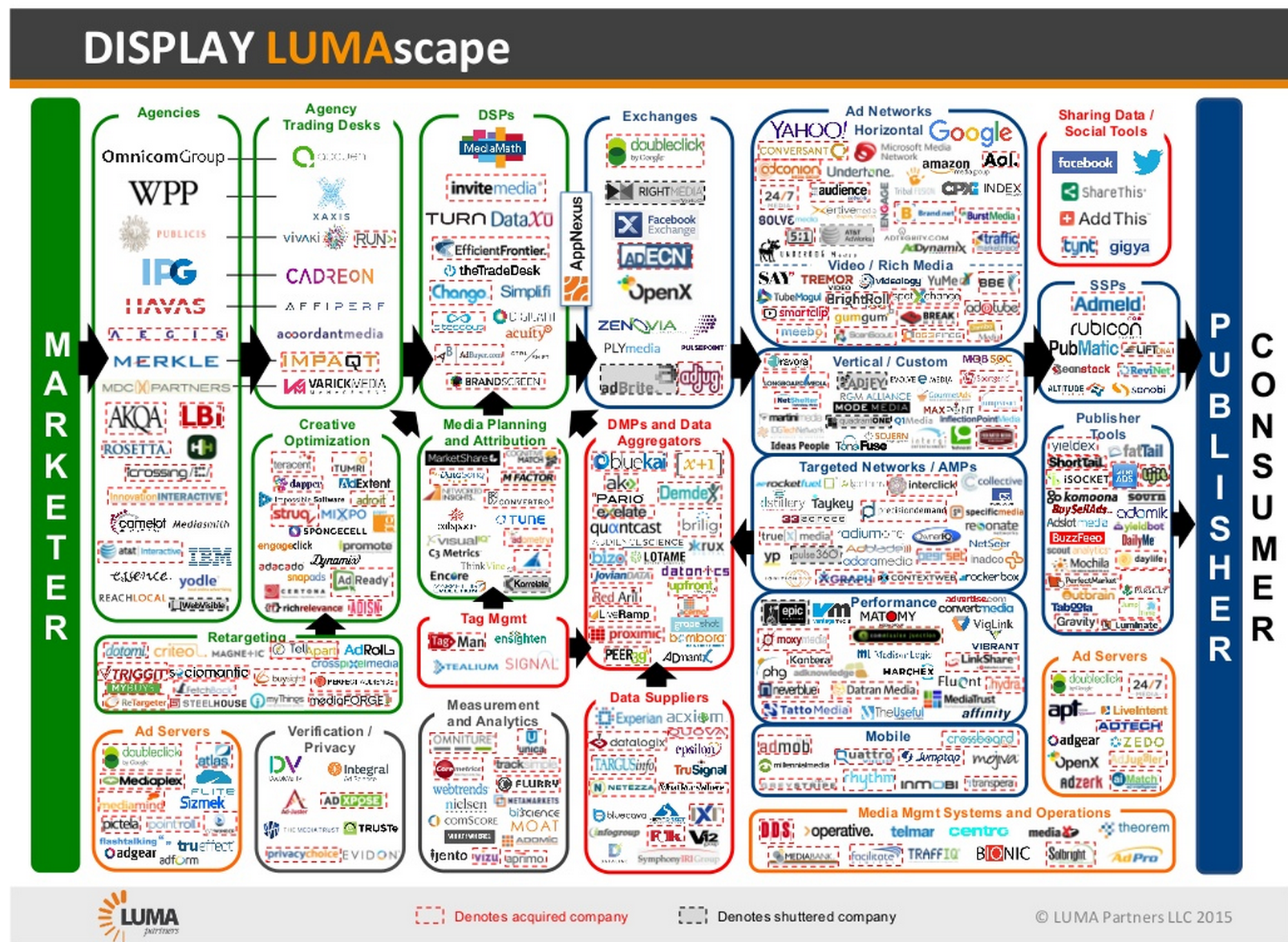

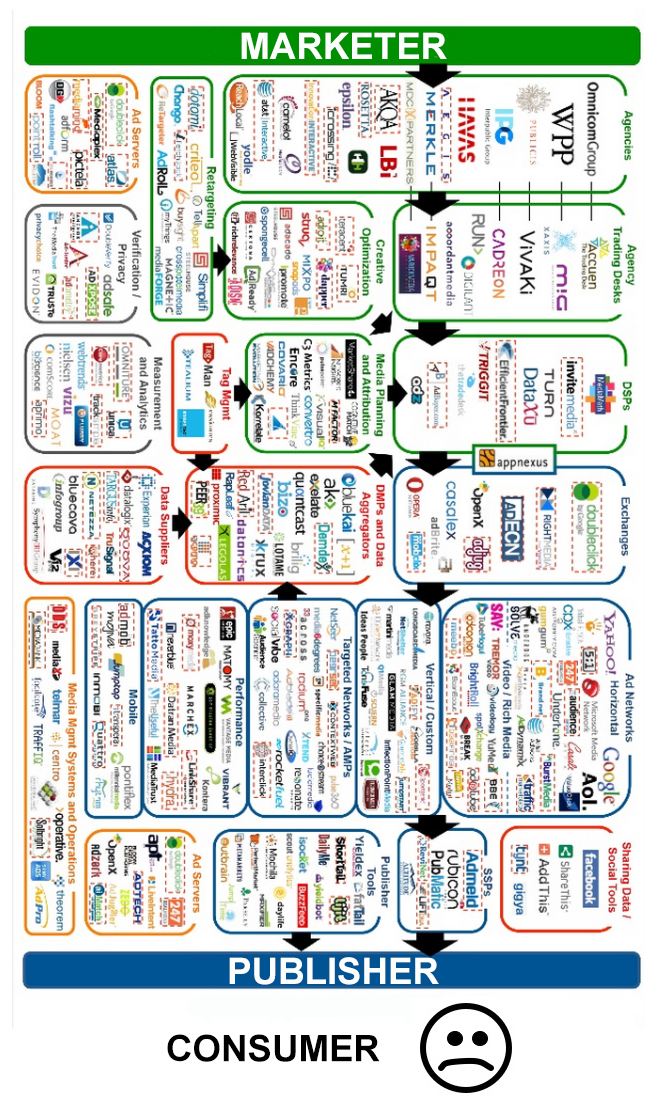

First, a huge percentage of Big Data work is devoted to marketing, and people in the marketplace are getting tired of being both the sources of Big Data and the targets of marketing aimed by it. They’re rebelling by blocking ads and tracking at growing rates. Given the size of this appetite, other prophylactic technologies are sure to follow. For example, Apple is adding “Content Blocking” capabilities to its mobile Safari browser. This lets developers provide ways for users to block ads and tracking on their IOS devices, and to do it at a deeper level than the current add-ons. Naturally, all of this is freaking out the surveillance-driven marketing business known as “adtech” (as a search for adtech + adblock reveals).

Second, other corporate functions must be getting tired of marketing hogging so much budget, while earning customer hate in the marketplace. After years of winning budget fights among CXOs, expect CMOs to start losing a few—or more.

Third, marketing is already looking to pull in the biggest possible data cache of all, from the Internet of Things.

IoT device vendors will sell their data to shadowy aggregators who live in the background (“…we may share with our affiliates…”)…

Second, in Harvard Business Review (@HarvardBiz), Ad Blockers and the Next Chapter of the Internet.

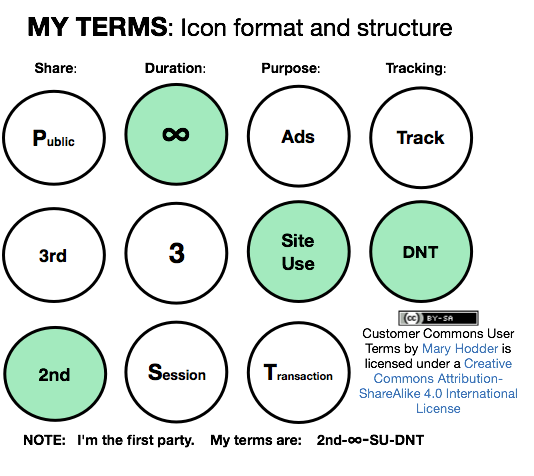

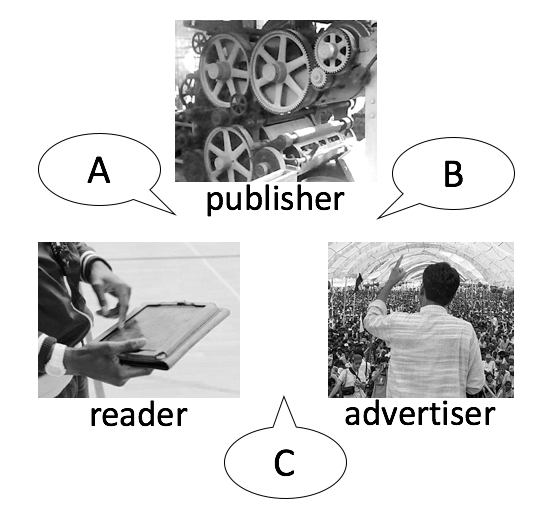

…look for new ways of setting terms of engagement that we each assert in our dealings online. In the past we had to accept the one-sided terms provided by websites and services. With the power to block content selectively, we can signal not only what we don’t want, but what we want and expect from the supply side of the marketplace.

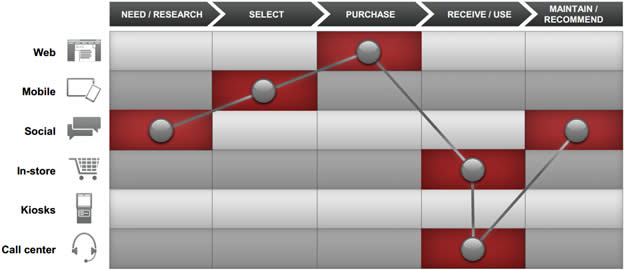

Customer Commons and others in the VRM (vendor relationship management) development community are also working on terms that only start with tracking preferences. These can expand to include conditions for voluntary data sharing, expressing buying interests, and providing standard means for connecting with loyalty programs, call centers and other CRM (customer relationship management) systems on the vendors’ side. Expect to see plenty of news about these and other expressions of individual agency online over the coming months.

Naturally, these will have important effects. Three stand out:

- The adtech bubble will burst. In October, executives with two of the largest publishers told me they are contemplating moves to back away from adtech. One of the biggest adtech spenders also told me they just dropped many millions of dollars in annual adtech spending. When these moves, and others like them, become public knowledge, expect to see surveillance-based marketing take a dive.

- Terms by which individuals deal with companies will solidify. Once that happens, we can expect The Intention Economy to unfold. This is an economy driven more by actual customer intentions than by expensive marketing guesswork.

- The new frontier of marketing will be service, not sales. Or, in the parlance of CRM, retention rather than acquisition. Additionally, as business becomes more subscription-based, service becomes dramatically linked to continuing revenue. This is a huge greenfield that will grow as more, and better, intelligence starts to flow back and forth between customers and companies.

After that, we’ll remember the adblock war as just another milestone in the short history of the internet. Post-war reconstruction, in this case, will begin with productive means of engagement, especially around maximizing agency on the demand side of the marketplace, and adjustments in supply to meet new and better-equipped forms of demand.

And if you’re worried about publishers and advertisers surviving, remember that publishers got along fine before there was adtech, and for most companies advertising is just one form of overhead. They can spend that money lots of other ways — including new ways they couldn’t see when they thought the supply side of the marketplace was running the whole show.

UMA, for User Managed Access

UMA, for User Managed Access