On this blog, I have put together six creative responses to weekly discussion readings. They deal with and express several different themes. Here I will pull out a couple of the major themes and discuss how my responses reflect these themes. They are: 1) authority and 2) the vernacular.

First, let us talk about authority. We have asked many questions related to authority this semester. Who has authority? Where do they get this authority from? Whom do they command authority? Is it political? Religious? I will strive to answer these questions for the relevant creative responses.

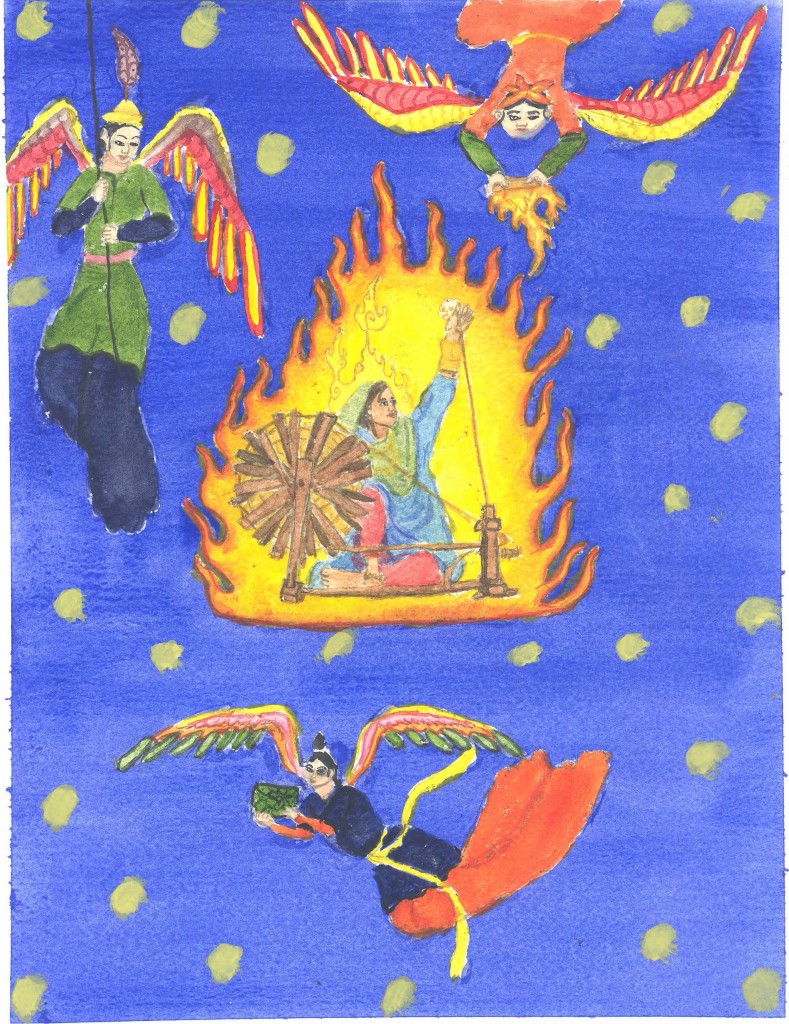

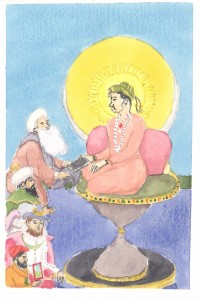

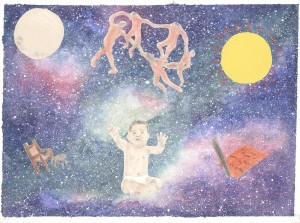

The Sufi folk poetry painting, though it may seem not to have anything to do with authority, does hint at the authority and position of the Sufi pir. As Eaton points out, the folk songs emphasized the importance of the pir as an intermediary between the singer and God. The pir has spiritual authority, drawn from a mystical/esoteric lineage traced back to the Prophet Muhammad. Thus he could claim to be the spiritual heir of Muhammad and imbued with the power that Muhammad commanded over spiritual matters. Notably, few Sufi orders actively involved themselves in the temporal and political realm. At the same time, a large number of non-elites, particularly women, enthusiastically gathered around pirs and participated in dargah worship. This following and popularity gave the Sufis enough influence to be noticed by political power players like the Mughals.

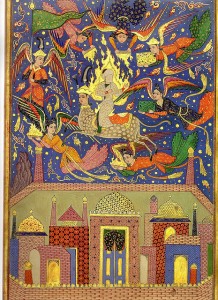

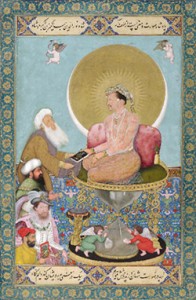

Speaking of the Mughals, my Mughal light imagery painting more directly addresses authority and power. Jahangir is positioned above both the kings and the Sufi shaykh, signifying his dominion over both the temporal/political and the spiritual/divine. The Mughals without a doubt had authority. Their political authority and power came from several sources: a Timurid/Mongol lineage of great conquerors with a history of military might; strategic alliances with local powers like the Rajputs solidified through marriage; a strong administration and bureaucracy; and economic policies that brought wealth to the empire. Despite this substantial political power base, the Mughals, starting with Akbar, also sought to draw authority and legitimacy from the Sufi Chishtis’ aforementioned popularity among adherents of many faiths. Akbar and later emperors established themselves as patrons of the Chishtis and their dargahs. Akbar also secured the power to interpret Islamic law in the case that the ulama disagreed. He thus positioned the Mughals as protectors of the spiritual, both popular (Sufis) and traditional (ulama). Using the Perfect Man concept and illumination philosophy, Akbar portrayed himself as a semi-divine figure responsible for the spiritual development of all his subjects who could be venerated by all of them. The spiritual dimension of the Mughals’ authority helped them appeal to the masses. They were connecting themselves with authority already recognized by the native population: the Chishtis.

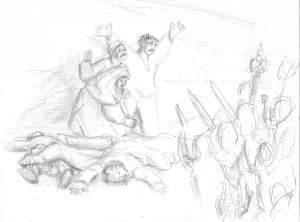

The struggle between Bengal and West Pakistan is also deeply related to authority. In many ways, rebellion results from loss of authority. After years of social, economic, cultural, and linguistic oppression, the people of East Pakistan decided that Islamabad’s authority over them was no longer legitimate. It was clear that West Pakistan was not using its authority to benefit Pakistan in any way. Perhaps that is a key to establishing authority. The people will give it to you if they get something in return, be it assistance, guidance, spiritual redemption, or protection. The American Revolution and the separation of Bangladesh both suggest so.

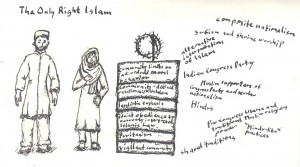

Similarly, Islamic fundamentalism is all about the community’s authority over individuals. It emphasizes uniting spiritual and political authority in the hands of the “right” Muslims, as determined by a narrow communalist definition. Part of this involves excluding other interpretations of Islam and Islamic authority.

I see the Gujarat Riots as an example of the failures of authority. For the secular state to work, all the citizens have to buy into the secular power structure and accept the authority of the state. In return, the state promises to protect the rights and persons of all groups, regardless of their religion, ethnicity, age, or gender. Opponents need to agree to trust in the political process and the secular society enough to conduct their battles in the civic realm, through the press and the legislature and the ballot box, not through violence. All of the above clearly did not happen in Gujarat. The government did not protect the Muslims. The Muslim community, both by circumstance and choice, didn’t integrate in with the rest of secular society. The Hindu nationalists’ rhetoric refused to accept the rights of Muslims as guaranteed by the modern secular state by massacring Muslims for their religious beliefs. Trust was broken, and without this trust in authority, a modern civic society, which ensures freedom for all its inhabitants, can’t function.

One particular question related to authority has popped up again and again: who has the authority to interpret and define Islam? The Sufi pirs, claiming to be the spiritual heirs of Muhammad, maintained their authority as intermediaries between worshippers and the divine. Yet they had a fairly inclusionary concept of Islam. Similarly, Akbar and Dara Shikoh used their temporal power to develop inclusionary definitions of Islam. Akbar controversially gave himself the authority to interpret Islamic law for the ulama. The conflict between Bengal and West Pakistan goes back a long time, to the conflict between the ruling class ashraf and the peasant converts of Bengal, the ajlaf. The converts practiced a different kind of Islam, which was seen as lessen or invalid by the ashraf. In this case, the ashraf claim the authority to define who is and isn’t Muslim. Finally, Islamic fundamentalism is all about who has the authority to interpret Islam. Mawdudi is deeply concerned with Pakistan being populated by “real” Muslims, who follow the same philosophy that he does. He give himself the power to define Islam, and focuses on the community’s authority to regulate the religion and lives of its inhabitants. The definition is all about excluding non-Muslims and adherents to other interpretations of Islam.

Now, let us move on to the vernacular. Though we spent a fair amount of time discussing why these terms are rather inaccurate, I will refer to the process of vernacularizing as a union between the “Islamic” and “Indic”. This mixing and matching (I hesitate to use the term “syncretism”) done across the South Asian subcontinent with the arrival of the Muslims synthesized new ideas and perspectives through translating concepts from culture to culture. Sufi folk poetry took an indigenous form and imbued it with basic Islamic principles. It ended up spreading the Sufis’ message to a whole new group of people through its appeal among lower class women. The Mughals also experimented with blending different religious traditions. Akbar and his descendants positioned themselves as semi-divine figures to be adored by all their subjects, partially through the practice of appearing at the jharokha balcony for darshan, an audience with their subjects. Darshan is a Hindu word referring to seeing and being seen by a deity or idol in a Hindu temple. In adopting this term for their audience, the Mughals incorporated native traditions in with their empire. Dara Shikoh also sought to unite the mystical traditions of Islam and Hinduism, feeling that they had a common root. The Tamil poetry is a great example of translation theory. That is, using one language to express the ideas of another language. Anapiyya uses the vocabulary of the traditional pillaittamil poetic form to compose a devotion to Muhammad, and in the process finds new and interesting equivalencies. In fact, he ended up making a piece of art significant both in the history of Islamic devotional poetry but also in the history of Tamil-language poetry (as considered by both Muslims and Hindus). Finally, the roots of the cultural divide between East and West Pakistan come back to the way Islam was incorporated into the vernacular in each place. Specifically, certain people who wanted to strictly define Islam had issues with the issues with Bengali’s “Hindu” roots and thus the “Hindu”-ish practices. In translating Muslim worship to the Bengali context, preachers had to find ways to express “Muslim” ideas in a language that had no basis for it. Yet I would argue that these moments of translation and mixing end up making the culture more interesting, more varied, and ultimately richer. A key for Hindu-Muslim-Sikh relations to move forward in the South Asian context is to recognize this history and process.