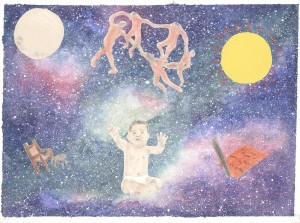

This mixed media piece is a response to Paula Richman’s “Veneration of the Prophet Muhammad in an Islamic Pillaittamil.” That article was from our “Boundaries in South Asian Muslim Literatures”, where we explored how South Asian Muslim authors found new ways to express “Islamic” ideas in South Asian vernaculars. I wanted to illustrate one of the cenkirai verses from the Tamil poet Anapiyya’s Napikai Nayakam Pillaittamil, which Richman analyzes in her article. In the Tamil language poem, Anapiyya venerates the Prophet Muhammad. He draws from a long history of Islamic devotional poetry but puts it in a highly structured traditional Tamil poetry form, the pillaittamil, wherein the poet, taking on a maternal voice, addresses a great figure (gods, epic heroes, etc.) as a baby while extolling their adult feats. Richman argues, and I agree, that the structure of the pillaittamil allows Anapiyya to praise Muhammad in new and interesting ways. Each section, or paruvum, has a dictated topic to address within its verses. For example, in the cenkirai paruvum, the speaker encourages the baby to sway back and forth and undulate its limbs about like grasses moving to and fro in the wind. In the cenkirai verse Richman analyzes, Anapiyya links baby Muhammad’s swaying with a cosmic dance celebrating him. Rumi also wrote about the universe dancing, but Anapiyya finds new ways in incorporate both traditions, as seen in the verse below.

Lotus-faced houris with eyes like lilies dance.

Celestials in heaven joyously dance.

The prophets and their sons, versed in revealed texts and commentary, lovingly dance.

The sun’s chariot, pulled by seven lively horses, dances.

The sun dances.

The ambrosial luminary dances.

The stylus and the tablet dance.

The throne and the footstool dance.

The heavenly city, best of worlds, dances.

The jinns and the many living creatures, produced by the great power of the Deathless One, take you as their ideal and dance.

Munificent jewel who returned after bathing in the celestial waters, play cenkirai.

Master Muhammad, Lord of the holy light, play cenkirai.

In my artwork, I tried to show the sun, moon (“ambrosial luminary”), stylus and tablet, throne and footstool, and heavenly inhabitants rejoicing around the infant Muhammad among the cosmos. As Richman writes, the stylus and tablet and throne and footstool are all Sufi mystical symbols “of power and magnificence associated with the divine unfolding of the cosmos.” I love the joy in Matisse’s Dance, so I used that as a model for my dancing celestials. All these figures were cut out and glued onto the galactic background painted in watercolor.

Dance (I), Henri Matisse, 1909. Held by MOMA. Image from MOMA’s website.

Paula Richman, “Veneration of the Prophet Muhammad in an Islamic Piḷḷaittamil

,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 113, 1 (1993): 57–74.

,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 113, 1 (1993): 57–74.

Post a Comment