Prologue

Coming into this class, I honestly thought that I would be learning about the same type of Islam that I learned in elementary and middle school. I am Muslim and for the first 13 years of my life, I attended a Sunni Muslim school in Maryland. Therefore, my foundational knowledge of my religion is heavily influenced my what I learned from my teachers. I never really questioned anything – maybe besides the mind-blowing concept of Qadr or destiny and if humans really had free will. But I digress. I did not expect that we would go through an in-depth cultural studies approach of Islam and analyze different denominations of the religion other than the majority Sunni one. For a lot of my young adult life, I’ve been craving to know what actually created the Sunni-Shia divide and what Sufism actually was. It was also a new experience for me studying religion through artistic lens. This opportunity gave me a new appreciation for the multi-faceted philosophies in my religious tradition.

One of the concepts that I will never forget is that what the religion was first introduced, it was much more inclusive and those who submitted to God (i.e. spiritual people, Jews, and Christians) could be considered muslims and followers of islam. When the religion started to gain more political power, followers of the religion wanted to distinguish themselves from others and became Muslims, followers of Islam. These blog posts are a reflection of me in a way discovering the hidden treasures of my faith and uncovering different interpretations of mundane traditions and practices.

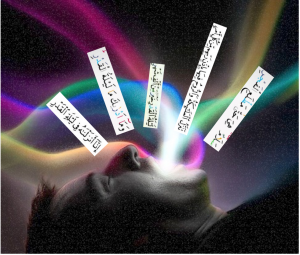

My first blog post from Week 3 discusses the recitation of the Quran. During my time in Islamic School, we had a Quranic Studies period where we would read and memorize verses and chapters and have the teachers test us on our memorization. We went over tajweed rules. In this class, we went more in depth of the significance of the Quran as not just a written religious scripture but also as an oral tradition. I realized that the Quran is a work of poetry and that there are many styles of recitation. In my piece, I express the importance of tartil, which is the style of reading the Quran slowly and clearly. This is why I include verses that have the vowel markings on them and space them out roughly equally from each other. Depending on what kind of emotion you want to convey or what cultural background you are from, your Quranic recitation will reveal these differences. This diversity is something I tried to convey with the different colors of the letters in the verses and the rainbow color in the background. Although I was brought up to focus on the meaning of the Arabic words I was reading, it was nice to appreciate the Quran for its poetic verses and musicality in recitation.

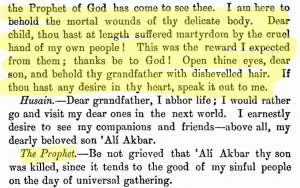

My blog post from week 5 reflects the stories of Prophet and his companions from the Iranian storytelling lens. The taziyeh was one of the main artistic outlets used to educate the masses about their Shi’a beliefs. I had only heard negative things about Shi’a Muslims coming from a strict Sunni background, so I was eager to clear up the misconceptions I had learned. We discussed the traditional performance of the martyrdom of Hussain and his family by Yazid in Karbala, Iran. This theatrical art form is a very deep part of Iranian culture and humanizes Shiites by showing the persecution they went through in a Sunni dominated environment. In Sir Lewis Pelley’s, The Miracle Play of Hasan and Hussein, the scene that caught my eye was when Husain is about to be slain by his enemies and he sees his grandfather, the Prophet. The Prophet comforts him using a prominent Shia concept of the pious people always having to suffer in this life. He assures him that his suffering in the world will be rewarded with something better in the afterlife. Even though it is human nature to feel betrayed by the people that want to kill him, his piety and transcendence above basic human feelings is revealed, as he eagerly meets his family in the afterlife instead of dwelling on the betrayal. Learning about this story definitely humanized the Shi’a tradition in my eyes, as I can understand the great confusion that there was after the Prophet died and no clear appointment of a leader after him. However, this confusion definitely does not justify murder of anyone, especially the Prophet’s family.

My blog post from week 7 discussed the Beggar’s Strike, a Senegalese satire of the transactional relationship between the common people of the town, the beggars and the marabouts. Reading this story took me back to the days of my childhood, where I’d read stories about Muslim people and that had an underlying Islamic moral. I was also excited to read a story from an African perspective, as Islamic education is often overpowered by Arab and South Asian perspectives. The concept of charity, which is a pillar of Islam, was examined as not only a religious tradition, but as a practice already embedded in the Senegalese culture. A major theme of the story was the sincerity of Mour Ndaiye. He was solely preoccupied with advancing in society and used every avenue he could to accomplish his goal of becoming Vice President. In my drawing, I depict him being pulled in different directions by the other characters in the narrative and how his relationship with God is weakened due to his selfish ways. One part of the story that stuck with me was when one of the beggars noted that he knew that the wealthier townspeople didn’t really care to improve their condition, but rather, they cared more about their self-preservation and the fact that they were getting prayers and blessing in return for their money. The marabouts are also somewhat satirized, especially Serigne Birama, who gets jealous that Mour is consulting another marabout about how he should deal with the beggars and therefore increase his status. Interestingly, the transactional relationship between beggars and townspeople had already existed prior to the application of an Islamic lens of giving charity. The marabout is also a powerful player in the story because he acts as an intermediary between God and the people. His sincerity is also criticized because there is doubt in the reader’s mind on whether he advises people for the sake of Islam or whether he cares about the food or money he gets from his clients more. Besides religious factors, postcolonial structures also play a part in the story, as one of the reasons Mour wants to get rid of the beggars is to attracted white tourists to the city. One difference between the religious stories I used to read as a child and this story is the presence of God. In my childhood stories, God plays and active and visible role in the characters’ lives. This depiction of Allah is intentional, as to teach children of God’s power. However, The Beggar’s Strike shows a more realistic and mature vision of God as working in mysterious ways and not being at the forefront of the action.

My blog post from the first part of week 10 discussed the reformist and revival Islamic movements during the 18th to 20th centuries. Despite going to an Islamic school for so long, we barely learned about the history of Islamic empires and the effects of colonialism and post-colonialism on the regions in Africa and Asia. Surprisingly, I only learned some things about them in high school, and small snippets from my college friends and the news. We learned that these movements were a response to colonialism and the destruction of Muslim Empires. These reformist movements emerged as as a solution to this problem. Professor Asani captured the sentiment perfectly, suggesting that the Muslims asked, “what was going on? Why were the non-Muslims being favored while the Muslims that submitted to God were not? We must be doing something wrong.” There were fundamentalist movements like Wahhabism, where some Muslims thought that God had abandoned them because they were no longer practicing Islam the “right” way – a strict fundamentalist interpretation of the religion that shunned other denominations. They targeted practices like visiting shrines, music and dancing of the Sufi tradition, emphasizing the principle of tawhid, or the oneness of God. In class, we discussed how this ideology was “as much a product of political and economic considerations as of religious dogma” (Lecture Notes). The founder, Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab, studied under fundamentalist Hanbali scholars and came to the conclusion that traditions like Shiism and Sufism were not based in Islam. This strict ideology was able to stay put in the Arabian region first by the addition of Abd al-Aziz ib Saud’s military power and the legitimization they got from the Western powers to combat communism. V. Nasr also how movements like these inspired the rise of jihadism and reformism in West Africa and Southeast Asia. There were a variety of other movements in the Islamic world, like those that sought to imitate or replicate Western models, like the establishment of the Turkish nation state by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk or liberal “back to fundamentals” like Sir Sayyad Ahmad Khan in India who argued that Western and Islamic thought were compatible. For this blog post and my artpiece above, I wanted to focus on revivalist movements that moved to stricter interpretations and practices of Islam around the world. I use red cones that stick out from the Earth and look like tornadoes as a way to represent the way they disrupted the land and literally divided Muslims in these regions. There is danger in condemning the interpretations of other Muslims, as many Muslims around the world dislike the Wahhabis strict practices even to this day. Islam has a tradition of being interpreted in many ways, and when people try to say that one interpretation is better than another, there is risk for severe division.

The second part of week 10 was spent discussing “Muslim Women and Defining Identity” – veiling and feminism. As a covering Muslim woman, I was very keen on hearing about the history of veiling, the interpretations for and against the physical headscarf, and the opinions of my classmates. I had never really questioned why I wore the scarf because it was part of my uniform in Islamic school and our teachers taught us that God commanded all women to be veiled to be modest. However, sometimes, I’d see my friends outside of school not wearing it. Some of my Muslim friends in college don’t wear the headscarf. Was there a clear answer on whether it was obligatory or not? I knew I might not find the answer in this course, but it was worth a start. There are several Quranic verses like (24:30-31) that tell men and women to lower their gaze and practice modesty and (33:59) that tell women to cover themselves so they can be identifiable as Muslims and saved from sexual assault. From a western perspective, it seems like women are oppressed in Islam, and that they must shrink themselves to avoid men’s arousal. This poem is inspired by my views on veiling. Taking this class was very interesting, considering that even though there were several other Muslims in the room, I was the only one covering. It made me feel a little self-conscious, because I felt like people would look to me as a physical symbol and representative of my faith, or that I was supposed to know all the answers to Professor Asani’s religious questions. Though I’ve been more confronted by this question in college, I’ve come to the realization that I may never know the right answer. Just because there is an array of interpretations that may make the veil obsolete, I’m not willing to give it up so easily. But, this means that I have to find a reason that makes sense to me, and maybe I have to be comfortable with my choice.

Finally, I was inspired to end my blog posts on a spiritual note. In week 11, we discussed cases studies of reform and revolution: one in Pakistan inspired by Muhammad Iqbal, and the other, the Iranian Revolution. Thinkers like Iqbal emerged during the reform movements in the postcolonial era. They believed in empowering Muslims through adaptive and integrative methods, in other words integrating Western “foreign” models within an “Islamic” framework. Muhammad Iqbal was an Indian-Muslim poet and philosopher who was influenced by European and Islamic thinkers like Rumi and Al-Hallaj. In my drawing for this week, I decided to focus on his famous concept of khudi, which is a new conceptualization of the self. Different from the Sufi term nafs, which is the ego that must be annihilated in order to bring a person closer to God, one’s khudi should be embraced. It aligns with the belief that I have that humans were born in a pure inclination or fitrah, towards goodness and God. Ultimately, the problems in the world and societal views taints our fitrahs and our purpose in life is to try to keep coming back to that pure state. We all have the potential for greatness when we struggle in this life and do good deeds to become better people. In my drawing, the soul is the white form and it has almost achieved its true form, in other words becoming yellow and purely full of light. The green background represents the impact this purified soul has had on the world around it. I left the head of the soul white because the mind is the hardest part to change in a person. Iqbal says that that one must forfeit aql (rationality) to achieve ishq (love) in this spiritual transformation (p.178). The author criticizes this extreme replacement of aql for ishq, which I agree with, and which is why I also left the head white (p. 179). I agree with the author in that a person can use ishq and aql together to face the world and makes changes. I ended my blog posts on this note because it represents the place I am in my spirituality currently. Though it is very difficult to keep my faith with the terrible things happening in this world, I find comfort in knowing that philosophers like Iqbal have an optimistic view on how all humans can change the world for the better by changing themselves.

My blog posts follow my journey through the cultural-studies approach of this course and help me reflect on my now ever wider perspective of my religion.