Welcome to my Blog

May 8th, 2014

This blog contains artistic responses to the materials covered in the course, “For the Love of God and His Prophet: Religion, Literature, and the Arts in Muslim Cultures.” The Cultural Studies approach used in the course changed the way I think about religion. For Islam in particular, we come to studying the religion, whether we realize it or not, with preconceptions. From what we’ve seen in the Media, with coverage of violence, and terrorism, these stereotypes are often negative. Islamic Art seems to be confined to museums, a thing of the past, entirely separate from modern-day Islam. But this need not be the case. This course demonstrated to me the inextricable nature of art, religion, and culture. Looking at religion through culture, and art, reinforces the multiplicity of religious experience. As our professor has often asked us, what do we really mean by the term “Islam” with a capital I. Often, the noun is used as though it possesses an agency of its own: “Islam says…” or “Islam forbids…” However, the most powerful concept that has stuck with me from what we have learned is that each individual’s experience of Islam is different, shaped by the culture, space and time.

This blog aims to convey this diversity of interpretation. Granted, all of these responses are tied by the common thread that they are from a course about “Islam.” However, each one is unique, created in a different media, with its own inspirations and message. My latest post, “Beat the Hate” was my way of engaging with the largely media-driven preconceptions about Islam that I came to this course with. Through this audio piece I wished to provide a dialogue between ideas about Muslims and terrorism and the frustrations of Muslims living in the West who are subject to these stereotypes.

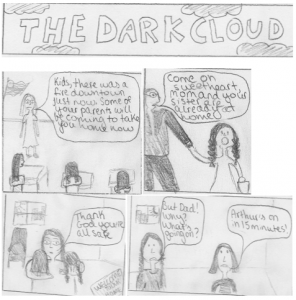

There is no doubt that 9/11 changed the reality of being Muslim in the West. In my post “The Dark Cloud” I deal with 9/11, but not in the way one usually sees it. For this post, I drew on Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis. I liked the way she used a child’s gaze to frame a historic narrative. In my case, I wished to express the fear and blindness that accompanied the event- not just because I was a child, and therefore had a limited understanding of my surroundings, and big issues, but also as any New Yorker at that time. Initially, so little was known, and initial reactions were feelings of violation, fear, blame and suspicion. Even when the perpetrators were known, everyone had their own ideas, their own stories and conspiracy theories. In a sense, whether we are a child or not, our reception of news and our understanding of tragedies is equally fragmented and subjective.

One of my very first pieces, a video taken during spring break, “People of the Book” also addresses questions of vision, and perspective. When I studied religion in school each religion was presented as an entirely distinct entity, neatly packaged in textbooks called “Judaism,” “Christianity,” and “Islam.” However, when I was visiting Jerusalem I was struck by how much these faiths overlap. Of course, I knew that these religions share teachings, but what struck me in Jerusalem is how much these religions share, even today. This is rendered ironic in a country like Israel, where we are so aware of the divisions between religions, particularly conflict between Jews and Muslims in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Yet, at the same time, in the old city of Jerusalem I was struck by how much the different “People of the Book,” as they are referred to in Arabic, coexist. I would turn one corner and find a road with mostly Arabic writing and the sounds of the call to prayer, then turn another corner and find a guided tour from Christian tourists visiting the stations of the cross, just next to a street sign written in Hebrew. Azra Aksamija, one of our guest lecturers, played on this unity within division with one of her pieces, “The Frontier Vest.” She has designed one item of clothing that can be used by Jews and Muslims alike. On her website she explains, “Pointing at the shared histories and belief systems of Judaism and Islam, the Frontier Vest can be transformed either into a tallit, a Jewish prayer shawl, or into an Islamic prayer rug… While Judaism, Christianity and Islam share the belief in one God, belonging to one implies a level of exclusion from the others. Based on different religious practices, socio-psychological boundaries often generate spatial ones, which in turn reinforce these divisions further. The Frontier Vest allows for individual expressions of different belief systems.” I was really impressed by Azra Aksamija’s work as she challenges our perspectives. This is what I was seeking to do with this video. In the space of a few seconds I expose the viewers to all three Sister Religions, showing they are not so very far removed from each other, or mutually exclusive as we often portray them to be.

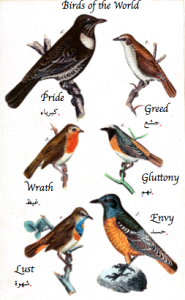

My other pieces are far less political in nature. I have used them more as a vehicle to develop specific readings that I found interesting, and give them visual form. Therefore, the issue of vision, and perspective, mentioned earlier is still important. For example, one of my recent pieces was inspired by The Conference of the Birds, which encouraged me to be more introspective. The piece is like a parody of a Birdwatcher’s manual. I have somewhat trivialized the complexity of The Conference of the Birds, and in no way seek to undermine it. Rather, I wanted to make a comment on what I see as very clear moral codes that are almost as clearly catalogued as different species of birds. The fake birdwatcher’s guide that I created acts as a guide for the individual. I called it “Birds to Watch Out for” because each Bird represents a flaw which we may recognize in ourselves.

Throughout our readings, film viewings and music listening during this class, I became very interested in certain images that I noticed were recurring. One powerful, and prevalent image is the very thing that allows us to see: light itself. I made one artwork playing with the concept of the Light of Muhammad, Nur Muhammad. The metaphor of Muhammad as a light, or as a lamp came up again and again in many things we read for class. I was drawn to this way of thinking about a prophet. In nearly all cultures I can think of light has become synonymous with knowledge, and learning. If I think back, even my elementary school crest had a lamp on it. If I think back to my childhoods, and my favorite Disney film Aladdin lamps can also hold they key to magic. The kind of lamps I saw in the markets in Turkey, where I took the picture that I used in this project, reminded me of the genies lamp. I think there is something of this magic in a passage we read, “…the almighty created the seed of the prophets out of a handful of His light… God decided that he would send one of these sparks to earth from time to time, and with it he would reveal the Light of His Wisdom…” I really liked this way of thinking about the prophets, or even of historical figures. Perhaps, the greatest geniuses, rulers, writers, actors and artists of this world were bright “sparks” created, and sent by God to leave their mark on the world.

One such great artist is the poet Hafiz, whose work s we read for section one week. I was deeply intrigued by the Ghazals we read. I think the idea of mixing the divine and the profane is provocative and extremely effective. By framing love for God with love in everyday life these poems manage to bridge the impossible gap. Ghazals gave me a deeper understanding of the Sufi path. This line of thought seems to have picked experiences that we undergo in everyday life that alter us, or make us crazy. These are as close as we can get to the utter loss of the self that occurs when experiencing the Divine. Two such experiences are love and wine-drinking. These phenomena are timeless. In fact, Beyoncé’s recently released hit song “Drunk in Love,” could speak to Hafiz’s 14th century poetry. The ghazals we read really spoke to me, as they include anxieties that we all experience, when in love, when out of love, and when confronting our own existence. Though we may not do the latter every day, the ghazals reach their profound questions through use of metaphors we can all relate to: the beauty of a woman’s lips, the sound of the wind, the drinking of wine. It is this last image that inspired my artwork. I was intrigued by the presence of wine in nearly every poem we read. In my drawing I play on what I had found in the ghazals, which were strings of images, created by words. When listening to a ghazal I would visual one image after the next: a nightingale, then a rose, then a wine cup. In this piece I have taken that to a literal extreme, made an image comprised of words. You see a wine bottle and glass first, and it is the words that physically form the image.

I hope that my blog will have a similar effect. I hope that, like my Hafiz piece, you will first see the image, or hear the sound, and then examine the words and meaning behind it. This blog cannot possibly cover every important theme that we have explored in this course, of which there were many. Instead, it is more like a cherry picking of certain topics that particularly sparked my curiosity. Moreover it is an illustration of a way of thinking, and learning that this class taught to me. I have realized the importance of zooming in, ad also of zooming out. In our lectures we covered vastly different areas of the world, from West Africa, to the Middle East, to India, to Malaysia. Doing so demonstrated the global nature of Islam as a religion. Each of these locations found relevance in our class due to their common religion, yet each was fascinating for its unique expression of this religion through culture. Within these I found fascinating instances of Islamic art- a coronation ceremony in Africa, a rap song in Pittsburgh, a film set in Iran. In many cases, the lines between culture, custom and religion were extremely blurred.

I think that this is why art was an excellent way of opening my mind regarding Islam as a religion. With some art, religion fades into the background, and is more of a cultural context. When we walk towards a beautiful glazed tile I a museum, we do so because of its forms and colors, not because it is in the “Islamic Art” wing, and, really, what does this label even mean. In other cases, religion is at the heart of art. In the Qawwali songs we listened to by Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, Sufi poetry, and love for God form the core dialogue, yet, an audience, regardless of their ability to understand the words of the song, would be equally mesmerized. I acknowledge that some of my blog pieces require explanation. Without the accompanying text, they may not make much sense. However, with these short descriptions, I would like to think that anyone can appreciate my work. And I hope, that, even if you are not familiar with the cultural studies approach, that the experience of reading my blog can make a case for this way of learning.

Beat the Hate

May 7th, 2014

I composed this audio piece using clips from youtube videos and clips from the song by the Sufi Rock group Junoon, “Meri Awaz Suno” which means, listen to my voice, in Urdu. I chose this song, because I feel that its lyrics speak to the frustration of many everyday Muslims living in the West who may wish their voices to be heard. The song requests freedom “Mujhe azad karo” and, this song requests freedom from stereotypes about Islam.

This piece was a reaction to Mohsin Hamid’s The Reluctant Fundamentalist but also to other discussions we have had throughout this class, including one about a film we watched, New Muslim Cool, about Puerto Rican American Muslim convert Hamza Pérez. In the film, a local Mosque that Perez is a member of is raided by authorities purely due to suspicion. When asked about the incident, Perez says “It just reminded me about the reality of being a Muslim in America today.”

Through this song I aim to portray a sad nature of that reality which is the suspicion that follows many Muslims living in America. I have sampled parts of the movie version of The Reluctant Fundamentalist as well as parts of the Bollywood film My Name is Khan in which a Muslim American of Indian origin travels across the U.S. to tell the President that he is not a terrorist. I also chose exerts from an ABC video that planted a bigot in a grocery store and got peoples reactions as he abused a Muslim employee.

By incorporating these different elements I aim to show the existence of Islamophobia and give a voice to those speaking out against it. The name of the song is a pun, that refers to the use of music ‘beat’ as protest. Music itself is banned by some Muslim groups, in fact we watched a very interesting documentary about the lead singer of Junoon and the opposition he has faced from more conservative relgious groups in Pakistan. Therefore, the spirit of this song, and his music is defiant, which matches the desire to speak out.

Birds to Watch Out For

May 7th, 2014

For this piece, I drew on Farid ud-din Attar’s The Conference of the Birds which we read for section earlier in April. I have used a birdwatching manual and have written 6 of the “7 deadly sins” both in English and in Arabic. The concept of “Seven Deadly Sins” is a Christian one. The flaws described in The Conference of the Birds are not as easily reduced. Yet, though more nuanced, many of the same themes appear in the stories of the different birds.

For this piece, I drew on Farid ud-din Attar’s The Conference of the Birds which we read for section earlier in April. I have used a birdwatching manual and have written 6 of the “7 deadly sins” both in English and in Arabic. The concept of “Seven Deadly Sins” is a Christian one. The flaws described in The Conference of the Birds are not as easily reduced. Yet, though more nuanced, many of the same themes appear in the stories of the different birds.

My decision to use a bird watching manual was twofold. First of all, birds and their stories in The Conference of the Birds are catalogued in a manner similar to a list of birds. Each bird: parrot, peacock, hawk, nightingale etc is recorded along with their character traits. Secondly, I believe that, like a birdwatching manual, the stories in The Conference of the Birds serve as a guide, but a moral guide. The stories are like cautionary tales. Each bird’s story has a human counterpart, and each bird exemplifies a flaw that is also found in humans. For example, the story of the nightingale, who is infatuated with a rose, is mirrored by the story of a dervish, infatuated with a princess. In both stories, superficial desires are rendered futile as the love is unrequited and unattainable. We are encouraged not to lose sight of the purpose of our own lives through infatuation with another.

My choice to use the Arabic name for the sins was an aesthetic attempt to connect this piece back to its “Islamic” inspiration. I also find the Arabic text more visually appealing, thus it lends more artistry to the work which otherwise would have the dryness of scientific manual. Finally, the Arabic flair indicates that this manual has a hidden dimension, which it does. These birds are more than objects of curiosity, they are also representative of moral flaws that we may find in ourselves.

September in New York, The Story of a Childhood

May 6th, 2014

This comic strip is inspired by Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, which we read for section last week. This week, we read another book, Mohsin Hamid’s The Reluctant Fundamentalist which deals with the effects of 9/11 on a young man’s life. In this response, I have drawn on both these books. I was actually living in New York in 2001, when the Twin Towers were attacked. I was in second grade at the time and had little idea of what was actually happening.

Like Satrapi’s memories of the Iranian Revolution, as recounted in Persepolis, my memories of 9/11 are still largely framed by my childish world view at the time. Of course, now, I understand what was going on. However, at the time, and to this day, the most vivid memories that stick with me are the little things that affected my daily routine as a second grader: being picked up from school early by my Dad (this was unusual as usually my mother came), not being allowed to watch TV with my sister, missing our favourite show Arthur and noticing the huge cloud of smoke when we went on our building’s roof terrace.

I found Satrapi’s use of the child’s gaze extremely effective when reading Persepolis. I do not believe that using personal memories as a way of framing historical events is a merely selfish exercise. Rather, I believe that a child’s unbiased perspective, like in the story The Emperor’s New Clothes sometimes reveals the greatest truth. In my case, I knew nothing. I had simply been told that there was a fire downtown. Yet, my sister and I could sense tension in the air. We knew that our parents, however well they had tried to disguise it, were also on edge. We knew that they did not know everything. I had the distinct suspicion that we were not being told the complete story.

My choice to depict 9/11 is two-fold. It is probably the single biggest historical event I have lived through, to date. It was also a day that would change the notion of “Islam” globally, forever. As Hamid so poignantly describes, after this event, life in the U.S. would never be the same for Muslims. With the fear and sense of violation that America felt came both heightened offense and defense. Within a few months was “the War on Terror,” in Afghanistan, and then the war in Iraq. Security at airports became the lengthy procedure it is today. Scrutiny of Muslims, men in particular became severe. I remembered hearing my Mum’s friend Waris, who has the unfortunate last name Hussein, complain that he was constantly interrogated in a separate room. I remember hearing how Bollywood’s biggest star Shahrukh Khan was also detained. Like a comic strip, these small snippets of news came to me, and, even as a child, I could tell things were changing.