Blog #0010: IPRs and Open Source

For me, one of the most frequently mentioned topics in high school was intellectual property. Lexington High School’s Honor Code addressed the necessity to respect individuals’ intellectual property; my economics class discussed the implications of IPRs on a country’s economic productivity; my US history class would often have debates around IPR policy as part of our current events section. Thus, when IPRs made an appearance in Where Wizards Stay Up Late, I was intrigued.

BBN’s initial refusal to release the IMP code was a blatant attempt to control every part of the current network— essentially, monopolize control of a unique resource. While the source code for the IMPs is not exactly a product being sold on the market, I find that many economic ideas are still relevant. If I may be visual for a second, here is a graph of a perfectly competitive firm:

We can see that economic welfare (basically the benefits society reaps due to the sale of the product) is quite plentiful. On the graph, the total economic welfare is represented by the sum of consumer and producer surplus.

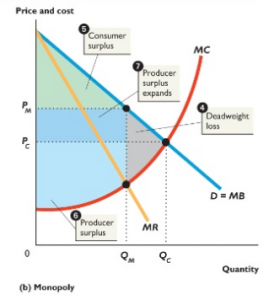

Now, here is the graph for a monopoly:

(Source for graphs: Essential Foundations of Economics by Robin Bade and Michael Parkin, 7th Edition)

Because a monopoly will choose to produce at a level below the demand for the commodity to raise prices, the total economic welfare is reduced. In our reading, BBN would be the monopolistic firm in question. The text mentioned “deadweight loss” (harm to society) such as the Network Measurement Center at UCLA being unable to function efficiently.

In this specific case, it was quite clear what the benefits and detriments of BBN keeping the source code private were. However, this caused me to wonder about the converse scenario— open sourcing. I remember hearing about Google choosing to open source TensorFlow and chose to read about it (here is the link, if anyone is interested). The basic idea of this particular article is that Jeff Dean believed that open-sourcing would make collaboration between Google’s researchers and other scientific communities easier and faster. In addition, individuals could improve the source code with few barriers.

Of course, as Satell includes as a caveat in his piece, total openness would harm a firm (hence Google keeping its search engine’s workings a secret). But generally, I see open source code as a great thing. Much like the RFCs had been at the beginning, I feel like they’re an invitation to join a larger community. They share a spirit with the ARPANET’s first users, who tinkered with the network on their own and contributed ideas freely. That’s how electronic mail came to be, and while I have a love-hate relationship with my inbox, it’s certainly connected the world in a new way. It’s evidence of how much this kind of innovative environment can cause great improvements in society.

However, I’m sure there are even more subtleties to IPRs and the choice between privacy and open-sourcing. I’d love to examine TensorFlow or another case study next week in our seminar. Until next time, then!