Dear Reader,

I struggled with the name of my blog. I wanted a title that was simple yet not cliché, original yet familiar, and personal yet universal. I eventually settled on a name that described the purpose of the blog: to document my journey through the course “For the Love of God and His Prophet: Religion, Literature, and Arts in Muslim Cultures” taught by the eminent religious scholar Ali Asani. I was drawn to this course because it taught religion in a way that made sense to me. I was raised in strict Pentecostal households in Kumasi, Ghana, and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Although I come from a devout Christian family and the majority of my closest friends are Christian, I do not identify as a person of faith. I believe that this is because I was never given the space and freedom to explore religion and faith in a way that made sense to me. I challenged myself this academic year to approach these topics differently. As the title states, this blog is my journey of understanding islam through art.

The most important points from the course that the reader should keep in mind while engaging with my blog are the following four terms: Islam (with a capital I), islam (with a lowercase i), “loud” and “silent” Islam. In lectures, Professor Asani defined Islam as the name of the religion and Muslims (with a capital M) as the followers of the religion. Similarly, loud Islam is an ideology and identity associated with elites (ex. Political and religious leaders) who want to assert their power over a population. In contrast, islam is an act of faith “submission” to God and muslims are the people of faith who submit to God. Silent islam is a muslim’s individual relationship with God. Loud islam often polices, controls, and silences this relationship between the devotee and God. I implicitly and explicitly engaged with these terms in each of my posts. For clarity, in this prologue, I will use islam and muslim without italics to refer to these terms more broadly.

On the first day of class, I sat on the floor in the back of the lecture hall because I was embarrassingly late. I did not know if I was going to enroll in the course, so I scrolled through Instagram, a social media platform, while Professor Asani explained the goals of the course. I looked up from my phone when he asked, “How do you know what you know about islam?” As he continued the lecture, I quickly realized that popular conversations on American television and social media platforms influenced my perceptions of islam. These conversations often defined islam by what it is not instead of what it is. They maintained Christianity and Christians as the “norm” and islam and muslims as the “other.” I also realized that voices and perspectives from the global Muslim community are often missing from these discussions. I returned to this question throughout the course and reflected upon it in my blog posts. I encourage my readers to also reflect upon this question to affirm and challenge their perceptions of islam.

Like my blog, I organized the remainder of this prologue thematically. In the following six sections, I will discuss my artistic process and how they relate to my journey in the class. I will conclude with my final thoughts about the course, islam, and my personal growth.

Week 1: Understanding God Through His Creations

The first few weeks were a whirlwind! I missed the second and third lectures because I thought I was going to take a different course. When that course did not work out, I scrambled to catch up on the lectures that I missed. Even though I went through the lecture slides many times, I did not understand the majority of the fundamental concepts presented in class. I tried to understand these concepts through the lens of Christianity. This approach, however, only increased my confusion and frustration. In class, it seemed like everyone understood these concepts except for me. I know that I should have gone to office hours, but I could not even begin to articulate what I needed clarification on. I almost even dropped the course. Fortunately, though, there were some concepts that I was familiar with because of Christianity and islam’s shared religious histories.

I was drowning, so I threw myself a lifeline by renting the book Islam: An Introduction by the religious historian Annemarie Schimmel. The book explained the concepts enough for me to better engage in class. It made me realize that I could not rely on Christianity to understand islam; I needed to understand it on its own terms. I went through the previous lectures and my notes with this new approach. It was successful; I found my footing in the course by the fourth week.

There were many excerpts from the Qur’an that we read together in lecture. The one that resonated with me the most was from verse 2:164. The quotation describes the signs from God that only wise muslims could recognize. I reflected upon this quotation when I was standing at the end of a pier in Newport, Rhode Island over spring break. I had a similar moment later in the break when I was at a botanical garden in Montreal, Canada. When I looked at pictures from other places I have visited I realized that if I was a wise muslim, then I would recognize these moments as signs from the divine. Therefore, for my first blog post, I decided to put these signs together in a video. For those who are not “wise,” like myself, the video shows the beauty of nature.

Week 4: The Power of Muhammad

I spent two days on campus between my trips to Rhode Island and Canada. A snowstorm trapped me inside, so I passed the time by playing with the oil pastels I bought for class. The drawing is simple, but the process of blending the colors and outlining the shapes took the whole day. The finished product reminded me of the nascent muslim community in the Arabian Peninsula that the Prophet Muhammad brought together during his lifetime. The artistic process was a small glimpse of how long and difficult it was for him to bring these communities together to submit to God. In the drawing, each community is distinct, but the prophet binds them together to create one image.

The following day, I partially burned my drawing to represent the fracturing of the nascent muslim community after the death of the Prophet. I decided to burn it to play on the light symbolism that we frequently discussed in the course. The fire was a symbol of power and the divine. Even though it pained me to destroy the drawing, I felt powerful watching it go up in flames. The power trip I felt is representative of the power struggle between muslim elites who vied for political and religious authority after the prophet. Despite the power rush I felt, I stopped the fire before it consumed the drawing. This action is representative of the mercy and compassion of the light of God.

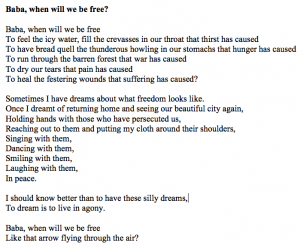

Week 5: Baba, When Will We Be Free?

Before spring break, I went to Professor Asani’s office hours to discuss questions I had about the midterm exam. The exam consisted of identifying ten concepts from a list of twenty-two from the course. I even surprised myself when I identified almost all of the concepts without referring to my notes. During the meeting, we also discussed how I could make an art piece about the Iranian taziyeh, a play that commemorates the death of Hussein, the grandson of the prophet, at Karbala (in present-day Iraq). I thought more about our conversation and the taziyeh over the break.

I wrote the poem, “Baba, When Will We Be Free” on the plane back to Boston from Canada. There was a baby a few seats from me who cried herself to sleep on her exhausted mother’s lap. The child’s distress reminded me of Ali, Hussein’s six-month-old son, who died in his father’s arms at Karbala. The taziyeh mostly commemorates the suffering of Hussein, his mother Fatima, and his sister Zaynab at the forces of Yazid ibn Mu’awiya of the Umayyad tribe. It—perhaps inadvertently—mostly silences the suffering of Ali. I wrote this poem to remind readers of the distress and suffering children experience when Muslim communities fight to assert their power over others. This reminder is important in the context of the current persecution of muslim groups around the world, especially in countries that do not get as much American media coverage.

Week 9: The Dance of Paradise

After the midterm, we focused on Sufism, the esoteric mystical outlook of islam, for two weeks. Specifically, we focused on Sufi music, dance, and literature. I especially enjoyed these two weeks because I spent time more time in and out of class listening to music and watching videos. Even though I could not understand what they were saying, I could see the emotion and passion on their faces. As I swayed and tapped along to the music, I felt as though I was “experiencing” the islam the authors wrote about in the translated poems I read. I even downloaded “Tajdar-e-Haram” performed by the singer and actor Atif Aslam on my phone.

I experienced islam again when I participated in a dance workshop led by dancers from a production of The Conference of the Birds, one of the best-known works in Sufi poetry by the Persian poet Farid ud-Din Attar. The workshop, like the course, was not what I expected. The dancers emphasized expressing ourselves through movement and communicating through touch. After the workshop, I reflected on different ways of producing and conveying knowledge to myself and others about experiencing islam. I used these reflections to make the short film “The Dance of Paradise.”

One of the movies we watched in the course, The Color of Paradise by the Persian filmmaker Majid Majidi, inspired my film. The movie centers on Mohammad, a blind Persian boy who experiences the world through touch and sound. One of the most moving scenes was when he wailed that if God loved him, then he would not have made him blind. When he told a blind carpenter that he wanted to see God, the carpenter responded that God could not be seen but he could be felt everywhere. I combined these moments from the movie and the journey of the birds in The Conference of the Birds to find God to create a film about the spiritual journey of a woman with physical disabilities. At the end of the journey, she realized that God is everywhere and inside of herself. I intentionally left the video simple to allow viewers to construct their interpretations of the story.

Week 12: #SayHerName

We focused on more contemporary topics in the last four weeks of the course. I was more familiar with these topics, but I was cognizant of the bias in Western media about events like the creation of Pakistan and the Iranian Revolution. The conversations we had about the intersection of Muslim reform movements and women in islam were especially interesting. They complicated dominant narratives about these topics in the West by asking questions like, which women; which Islam; and which context. I asked similar questions in conversations with friends and family members about women and religion.

During one of the lectures, a quotation from Benazir Bhutto, the former Prime Minister of Pakistan resonated with me. In the quotation, she states that if a muslim woman was declared half a man, then it was because the elites in power changed not islam. The quotation criticized elites who used muslim women and their bodies as the “objects” of their movements to institutionalize islam as an ideology for a nation-state. This loud Islam often sought to silence anyone who challenged their authority. The work of muslim women who protested against these ideologies even under the threat of violence and death inspired me. Unfortunately, this fight is global, ongoing, and not unique to muslim communities. I am involved in the #SayHerName movement which aims to raise awareness about the gender-based violence that black womxn face in America. I created “#SayHerName” to commemorate our intergenerational fight for the freedom and liberation of womxn from all forms of oppression.

Week 13: To God We Return

For the last piece, I connected my learning to tell a global story of unity. I included important moments, themes, and materials from the course that I did not explicitly engage with in the previous blog posts. The song “A Change is Gonna Come” by the African-American singer Sam Cooke is at the center of this piece. The song gives me hope that one day—perhaps in the afterlife—we will all put aside our differences and quests for power to recognize our collective humanity.

Conclusion

Even though an academic semester is not long in the context of a lifetime, I am proud of how much I learned and the art I produced in a short amount of time. I wanted this blog to be an extension of the new perspectives I gained from the course. There is not a specific “message” I want readers to walk away with after engaging with my blog. I do want readers to see that this was my journey of understanding the beauty and diversity in islam. As I said in the introduction, this course was the first time that I explored religion and faith in a way that makes sense to me. I hope to use this approach to explore other religions and faiths in the future. I am not sure where the journey will take me, but I am looking forward to it!

All the best,

Amma

Recent Comments