Before taking this course, my knowledge of Islam had primarily been informed by the mainstream media. Unfortunately for the probable thousands of Americans who shared this in common with me, there are so many misconceived notions of Islam depicted by these media outlets that may never be rectified unless an active search for truth is realized. Much of what the younger generations have seen in their lifetimes regarding Islam has been shrouded by dialogues of terrorism, war, and fear. It is a very instinctually human phenomenon to form an opinion and stick to it for pride or vanity’s sake. These opinions once formed are rarely able to be transformed, unless genuine open-mindedness and empathy are present. But fortunately for me, I came into Harvard almost entirely set on concentrating in the Comparative Study of Religion. Coming from a tremendously devout Catholic family, I had attended parochial school my whole life. Though I fell in love with my Catholic faith from a young age, I knew that reserving my religious studies to Catholic theology alone was detrimental not only to my conception of Catholicism, but to my conception of religion as a whole. Taking a class on Islam was a top priority on my list as I was aware of my own ignorance of both the religion and the culture. But people are not stringently bound by their ignorance that perpetuates destructive stereotypes. Misconceptions and misunderstandings can be easily cured with knowledge. And that is something I learned this semester.

In his book Infidel of Love, Professor Asani says: “It is one of the great ironies of our times that peoples from different religious, cultural, racial, and ethnic backgrounds are in closer contact with each other than ever before, yet this closeness has not resulted in better understanding and appreciation for difference. Rather, our world is marked with greater misunderstandings and misconceptions, resulting in ever-escalating levels of tensions between cultures and nations.” (page 1) These tensions that arise between cultures hardly exist on account of reasons other than ignorance. Nobody could ever come to truly know or appreciate another person, community, or culture without truly understanding that person, community, or culture. Learning about Islam therefore becomes an undertaking that requires the study of the historic, social, and political contexts that envelop the religion, before diving into the study of the modern-day conflicts existing within and surrounding some Muslim nations. Throughout this class, not only did we look at these political and historical contexts, but we also, more uniquely, examined Islam through the lenses of art, literature, poetry, and music. Peering into our subject through these aesthetic lenses provided an experience unlike any other approach to learning I’ve yet encountered. I hope the viewer will catch a glimpse of this from my blog posts.

In this blog, I present my own personal interpretations of and responses to Islamic art, literature, poetry, architecture, music, and culture. Each entry presents a reflection of the corresponding lecture material or weekly readings beginning with Week Two’s “Constructions of Islam” and ending with Week Twelve’s reading of Persepolis and Sultana’s Dream. As I mention in some of my blog posts, my spiritual life was fairly established before taking this class; but with each coming week and its accompanying lectures, my eyes were opened to so many new possibilities of approaching faith and life as a whole. Though I came to this class with a limited knowledge of Islam and, moreover, a mistaken belief that the religion along with all it promoted had no place alongside my own convictions, I am now ending the semester, delighted to have been proven wrong. My deepest hope is that someone stumbling upon this assortment of “mystical meditations and other miscellaneous musings” might recognize the collective revelations that have allowed me modest glimpses into enlightenment over these past 13 weeks, and even better, might also be inspired to think differently themselves.

In my first blog post, “Constructions of Islam,” I focus on the distinction between the terms “Muslim” and “muslim.” This was perhaps one of my favorite units in the semester because it set the stage so perfectly for all of the other misconceptions I was subconsciously harboring that would be broken throughout the rest of the course. I think that the aforementioned villainization of Muslims that has been presented in the media post 9/11 has created a false notion that at the core of Islam, exists a claim to salvation that precludes any non-Muslim from God’s mercy. But, something I learned in week two, primarily through Professor Asani’s second chapter of Infidel of Love, is that True Islam values all human life and recognizes the fact that fundamental human rights are not only universal, but that belief in this is a principal tenet of the religion. Contrary to the misconception, True Islam emphasizes that inherent dignity of humanity is derived from the same creator and therefore, rejects any possibility of ethnic, racial, or religious supremacy. As a recently declared concentrator in the study of comparative religion, I find this pluralistic message all the more critical for the development and fostering of understanding. I am a firm believer that we should not be content with the end-goal of tolerance. Tolerance implies a certain degree of complacency towards a subject, when what we should be striving for is appreciation for difference, and an eagerness to learn more about viewpoints countering our own.

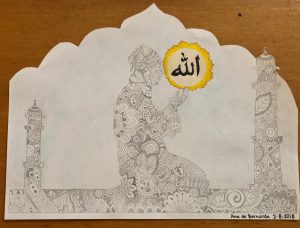

My second blog post turns towards a more aesthetic side of Islam. In week six, we discussed mosque architecture and heard from two guest lecturers who spoke about the fluidity and multidimensional nature of Islamic art. In Ismail R. Al-Faruqi’s Misconceptions on the Nature of Islamic Art, he prefaces the text by noting that “the Western scholars of Islamic art…have failed in the supreme effort of understanding the spirit of that art, of discerning and analyzing its Islamicness…they sought to bend Islamic art to its categories.” (page 29) This recurring phenomenon of Western societies misappropriating cultures outside of their own is one of, if not the singular, leading cause of the culture clash that Professor Asani references in the first excerpt from Infidel of Love. Not only are misrepresentations of these cultures counterproductive to the quest for understanding, they are simply erroneous and lazy assessments in which these Western scholars attempt to fit every other culture and society into the confines of their own constructed conventions. What I found so beautiful and unique about Islamic art is that despite the wildly varied modes of interpretation and expression, all “derive their theological aesthetic from the same principle, namely, tawhid, the acknowledgement and assertion of God’s uncompromised unity and transcendence.” (Rendard, Seven Doors to Islam, page 128) The artistic liberty afforded by this principle combined with the lack of a rigid architectural template for masjids leads to endless creative possibilities. I chose to follow up Week Two’s blog with Week Six because I think the plurality message tied into the first blog also comes through in this visual project. The incorporation of three cultures into the Spanish mosque architecture is a prime example of the productive relationship that can exist between nations, and the beauty that arises as a result of their cooperative effort.

The blog inspired by Week Five deals with the importance of historical contexts and the role history plays in shaping a culture. The relationship between the father, the son, and the grandfather in Elie Wiesel’s quote is one that helped me understand the importance of the Ta’ziyeh much more clearly. So much of history relies on story-telling and the passing on of customs, but many people undervalue the importance of preserving tradition. And yet, tradition is what so often lies at the heart of religion and group identity as a whole. Without tradition and a rich history, meaning can be entirely dissolved from a culture. I have seen firsthand the essentiality of this preservation within my own faith. It’s easy to question the Truths within your religion when you realize that you only subscribe to it because of your parents, and their parents, and their parents’ parents. But once you realize the weight of tradition, you grow to appreciate the history behind your own roots, and suddenly, there is so much more meaning underlying your convictions.

Transitioning into the second half of the course, my fourth blog revolves around Week Nine’s subject of Islamic poetry. This type of faith expression and the difficulty discussed in lecture of confining a spiritual experience to fit within the parameters of language is one that I was easily able to relate to. Throughout my life, I have had innumerable encounters with areligious people that lack even the slightest trace of faith. Trying to verbalize your own faith experience is almost an impossible feat, and anyone who has been in a similar place could likely attest. When the Transcendent is so infinitely above the worldly realm that we exist in, it would be a futile task to limit an encounter with It to time or space. This poem grapples with my inner battle between constantly seeking social validation and ultimately realizing that “the one who made the stars, for my heart freely yearns.” This sense of security of self that I find within my own faith is something that people in my life who have never experienced this may never understand. My sense of self is secure because it rests in the opinion of my creator, and I have realized more and more throughout this course that I do not stand alone in this conviction. I am convinced that the bond which exists between people of faith is unlike any other interpersonal connection that human beings could share. Not only does it transcend language and time, it automatically places you on an elevated state of understanding.

This sense of unity among the community of believers is exactly why I chose to shift into Week Ten’s Conference of the Birds. In choosing seven birds and seven languages denoting “God,” I hoped to encompass this theme that, despite possessing impossible differences, no single religion holds a monopoly over salvation. Like the Buddhist parable of the blind men and the elephant, I believe all religions strive towards the same understanding of the Divine and arrive at different interpretations. These differences, far from excluding any one faith from attaining the “other-worldly,” unite believers on a common journey of enlightenment. The lessons from this search for truth illustrated in The Conference of the Birds was one of my biggest takeaways from this course. I think people do themselves such a disservice in believing that their way contains the only Gospel Truth. There are so many different routes linking this world to the next. If a believer genuinely perceives the Divine as infinite, how would this not be the case?

This multiplicity of paths to the Divine is what inspired Week Twelve’s imitation of Persepolis. Though dealing more with my own spiritual journey, the comic strip template allowed me to depict the variety of examples necessary to highlight this theme. In high school, my sophomore year theology teacher taught us about Divine Revelation and the different ways in which God unveils Himself to humanity. There are so many areas of my life in which I see proof of this divinity so plainly. I’ve spoken with non-believers who are frustrated by the fact that if God exists, why shouldn’t He come down or show Himself to us? I find it so hard to stop myself in those moments and scream, “He’s right there! He’s in you, He’s in me! He’s in everything! Don’t you see it?” But evidently, the answer is ‘no.’ If I truly believe in an infinite, omnipotent God, shouldn’t it make sense from this conception that a direct revelation would be too much for my finite mind to comprehend? This thought helps me to search for the beauty and good in everything around me and recognize it as having its roots in the Divine. Whether that be reflected through love, through kindness, through nature, or even through suffering, all of these help me to appreciate my faith and broaden my own conception of my creator on a much grander scale. This past semester has only reinforced this belief. I was challenged, enlightened, wounded, healed, distressed, and relieved all at once and I could not be more thankful for this period of tremendous growth. It is my sincere wish that readers of this blog might experience the joy and hope offered by faith at some point in their lives, or if they already have, to hold onto it for as long as they live. Life is hard and suffering does not discriminate, but with faith, our burden is made much lighter.

Recent Comments