She’s an author first… context matters

Wednesday, July 16th, 2014When inadequate data is transferred from a handwritten description into an online environment, there is potential for promulgation of error.

For the 2014 Cambridge Open Archives Tour (http://www.cambridgearchives.org/OpenArchives) we pulled out some of our fabulous collection items. Among them was a recipe box.

Thanks to the need for exhibition labels, a colleague did a little background research and uncovered the true story behind it. From the old description (below), you’d probably conclude that this was a box of recipes very much like you find in your own kitchen–things picked up over the years, family favorites, and aspirational dishes that you’ve never even tried.

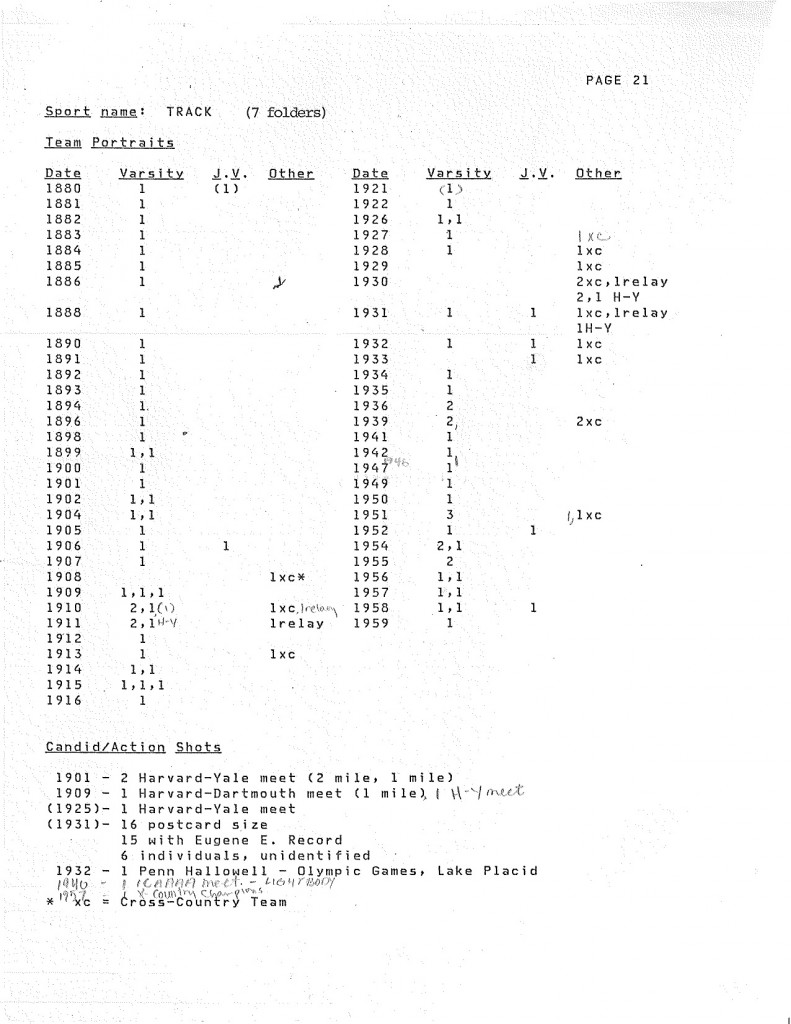

Here’s what the old record looked like. Click the link in the call number to see the current version.

| Author : | |

| Title : | |

| Location : | Harvard University Archives HUG 1436.40 |

| History notes : | Marietta McPherson was the first wife of Chester N. Greenough, a professor of English at Harvard University. |

| Summary : | Card file of recipes collected by Marietta McPherson Greenough, ca. 1920. |

| Subjects : | |

| Keyword Subject : | Harvard University — Faculty spouses. |

| Harvard University — Women. | |

| Form/Genre : | |

| HOLLIS Number : | 009359473 |

Giving all due credit to the “quick and dirty” catalog record for making the item discoverable, I nonetheless roll my eyes at the only context the record provides. “Marietta McPherson was the first wife of Chester N. Greenough, a professor of English at Harvard University.”

Full disclosure: I’m pretty sure I created this record.

In point of fact, Marietta McPherson Greenough was an author, cookbook collector, and an advocate of home economics as a field of study. Under the pseudonym Mary Green, she published Better Meals for Less Money in 1917. The recipes in the card file seem intended to cope with war-time shortages. Some were vegetarian or required only a small amount of meat, and the desserts call for only small amounts of butter or eggs.

This biographical note that limits itself to who her husband was–when the recipe collection is so clearly the product of her own research–arguably constitutes error. (If one of my students had done this, there’d be some fairly copious comments on their assignment!)

When inadequate data is transferred from a handwritten description into an online environment, there is potential for promulgation of error and bias, as well as the welcome possibility of being called out on error and bias. Such old descriptions are often the source for “quick and dirty” catalog records. The inaccuracy and bias in this case derive from an outdated view of the archives, an outdated view of the world, and an outdated expectation about what researchers want. Once upon a time “wife of professor X” was the only presumed role of significance, the professor the presumed topic of research, and the professor’s papers their presumed resource of choice.

One of our visitors at the Cambridge Open Archives Tour remarked on how many of our staff were women. I’d like to think any archivist today–male or female–would appreciate context and recognize research value.