Wednesday, June 22nd, 2005...6:21 pm

Byzantine Art: A World of ‘Phantasma”

A World of ‘Phantasma’

Justo J. Sánchez / New York

Two-Sided Icon with the Virgin Pafsolype and Feast Scenes and the Crucifixion and Prophets. Byzantine (Constantinople?), second half of the 14th century. Collection of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, Istanbul. Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art has achieved the inconceivable: it has made a Byzantine art exhibit a blockbuster. The amazing feat was possible only through diplomacy, tenacity in negotiation, dedication, and love of art. “Byzantium: Faith and Power” includes masterpieces from as far away as Meteora, Mistras, Istanbul, Konya, Moscow, and a great collection of icons from the Holy Monastery of Saint Catherine, Sinai, Egypt.

Professor Thomas Matthews of NYU’s Institute of Fine Arts argues that the armies of the Fourth Crusade dismembered the Byzantine Empire in 1204 “Prepar[ing] it for its final dissolution.” The Byzantines however “were able to overthrow their Western lords in 1261 and re-establish a much-diminished empire. In this third or Late Byzantine phase, art found a new humanism that appealed strongly to surrounding countries and influenced profoundly the Italian Renaissance.” (Matthews, Byzantium. New York: Abrams, p.12.)

The third in a tripartite examination of Byzantine art at the Metropolitan, the exhibit resumes the narrative at the point when Michael VIII Palaiologos entered Constantinople in 1261 with the icon of the Virgin Hodegetria. From the period under scrutiny (1261-1557), the viewer has the opportunity to observe a variety of media: illuminated manuscripts, fragments of mosaics and of architectural elements, sculptures, liturgical implements, reliquaries, and icons.

Mosaic Icon with Christ Pantokrator. Byzantine (Constantinople), 1300–1350; Parish Church of Saints-Pierre-et-Paul, Chimay, Belgium. Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art

There is a syntactical orthodoxy in the Byzantine discourse, a constant in its thousand-year history. The transcendental and fixed nature of its universe of discourse and its signifieds, account for the continuity in grammatical rules of composition and representation. The miracles attributed to certain icons help explain the lack of radical artistic experimentation. The specificity of syntax anchor semantic relations. The placement of arms, the location of certain objects, even facial features of expressions, distinguishes the characteristics of a type of Virgin, apostle, saint or angel.

<!–[if !supportLineBreakNewLine]–>

<!–[endif]–>

There may be certain calligraphic changes that point towards a new humanism and realism as in the early XIV century icon with the Synaxis of the Apostles from Constantinople or in the sanctuary doors with Saints George and Demetrios from XV century Crete or in the Getty’s Nicaean Tetraevangelion from the XIII century. These works show that within the parameters of a rigid grammar, it was possible to allow a measure of stylistic change. It just did not happen at the same increased tempo of the West where the winds of change took Europe from the Romanesque to the Gothic magnificence of Chartres, Notre Dame, Burgos, Cologne and found itself taking a leap to the radical paradigmatic transformation of XV century Florence. In the visual arts, the West moves from Berlinghiero to Cimabue to Giotto to Simone to the Renaissance, or from Ottonian manuscripts and late versions of the Beato to Pucelle’s Hours of Jeanne d’Evreux and the Très Riches Heures.

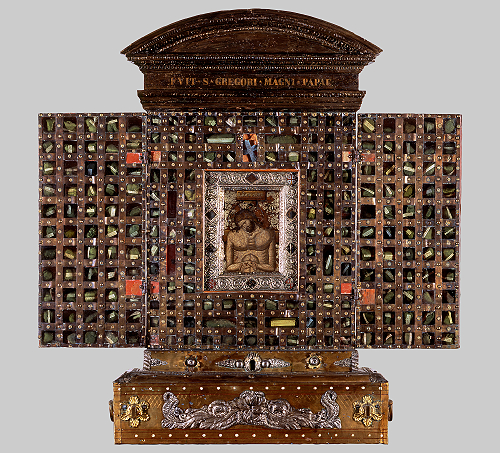

Mosaic Icon with the Akra Tapeinosis (Utmost Humiliation), or Man of Sorrows. Mosaic icon, Byzantine, late 13th–early 14th century; icon of Saint Catherine (reverse), late 13th–early 14th century; case, late 14th–17th century. Basilica di Santa Croce in Gerusalemme, Rome. Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

“Byzantium: Faith and Power” is about tradition and faith in the face of a dwindling empire, about a visual discourse in different media that upholds a metanarrative. At a fundamental level it is about the role of imagery in Christianity. The visitor witnesses how an icon or a mosaic image or a religious vestment can perform many functions. It can sanctify an environment, it can “protect” the holder or his community, it can teach a lesson, it can place the viewer within the context of a religious tradition, it can “recall” a presence to memory, it can become transparent as a window to transcendence or vehicle to prayer, it can stand in place of the absent or invisible, in this case holy entity.

Most of the images presented in the exhibition have a connection to ritual where they serve to establish an institutionally-mediated connection with transcendence. In a typically conservative, orthodox fashion, it is the institution that governs the rules of grammar and construction for the visual language used within its confines.

The exhibition’s icons, liturgical instruments, and vestments indicate that this is a visual culture that resonates with mystery and mysticism. The ceremonies of Christianity took place behind iconostasis, “mysterion,” secret or closed rituals except for the initiated (“myste”). Christianity was for the baptized. Only the priests or deacons could enter behind the veil of the iconostasis. Only the initiates (the baptized) could participate in the holy liturgy. “Myein” is to close shut, as lips in secrecy or the doors of the iconostasis.

Byzantine art emerges out of contradiction in its attempt to make the invisible visible. In an effort to represent the divine in two dimensions, it uses the human dramatis personae in the Judeo-Christian narrative of salvation: Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary, the Apostles, and the Saints as well as some of the Old Testament prophets. Byzantine art responds to a drive for “phantazein,” to make visible. In Timaeus, Plato offers an account of why we dream and our dream images “phantasma.” Imagery is similarly conceived in Plato’s epistemology. The images in “Byzantium: Faith and Power” are “phantasma” inasmuch as they are shadows of an otherworldly reality. They obey a “phantazein” need for figuration, of intelligibility through vision, and the need to make a space holy. They float as ethereal apparitions reminding the viewer of transcendence.

1 Comment

July 7th, 2007 at 4:30 pm

Certainly a great. But the first thing that struck me is the phrase, “Byzantine Art:” It reminds me of my higher diploma days while a studenr of Fine and Applied Arts. Really I love art history a lot but didn’t agree with few things.

Thanks for sharing this us…

most effective acne solution