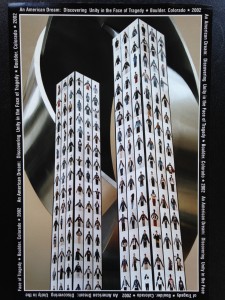

Like many, I have a 9/11 story. I was a high school junior in Boulder, Colorado, and that day permanently popped the “Boulder Bubble” I’d been inside. Naive to global politics but deeply affected, I spent the rest of the school year leading a wearable art project with 150 middle school students in response. It was called “An American Dream: Discovering Unity in the Face of Tragedy.” Each kid decorated a denim jacket to express their thoughts and feelings. I photographed each of them in their jackets and made towers of the photographs to represent our united diversity. We had a big exhibition of the towers and the jackets, and we sold the latter to raise money for New York City middle schoolers near Ground Zero. Here is a picture:

Ten years later, I was living in New York, feeling dissatisfied by my budding nonprofit career. I didn’t want to become a fundraiser; I wanted to do things that united communities through the arts—like that project we had done after 9/11. So I enrolled in a couple of classes at NYU, including one called Creative Programming for Arts Institutions. I ended up being assigned a project to design opening activities for the National September 11 Memorial and Museum at Ground Zero. I proposed a slate of public programs centered on uniting the community through song. School choirs from around lower Manhattan were to perform a Sunday Sunset series of songs focused on unity, healing, hope, and growth. Here is a slide from my final presentation:

Two years later, I finally realized that my interest in uniting communities was more than passing. I applied to Harvard Divinity School with the express intention of fostering diverse and meaningful community through creative collaboration.

On this whole journey, and in my first two years at HDS, I never studied Islam. Though I dismissed the rhetoric that blamed all Muslims for 9/11, and lamented this country’s rising Islamophobia, I also had no idea that unity in diversity – the very thing I was seeking – was at the heart of Muslim faith. Discovering the spiritual foundations of Islam has been, for me, the great joy—and long overdue lesson—of this course.

I have chosen to focus my blog on that discovery process. In particular, I have sought to explore and reflect upon the unifying force of divine love that has been a touchstone of our semester. I remember our first section in which Ceyhun asked if any of us could recall the course title. It is not every day that one signs up for an experience with such a lofty (and promising) name! For the Love of God and His Prophet…Even after years in divinity school, it struck me that this was to be a different kind of course, one that engaged with history and politics and doctrine, yes, but also, deeply, with devotion. That here we would examine religion, literature, and the arts in Muslim cultures through the lens of love.

At least, that has been my lens, and I invite you to share it as you take in the following posts and creative gestures. Each is a statement of inspiration, and taken together, they represent my journey into the heart of Islam this semester. I tried to be practical in my questions about love in Islam. How is love working as a force to unite communities? What is the role of the arts in that work? Precisely how is the love of God seen, felt, practiced, articulated, illustrated, experienced, and artistically expressed? In particular, I was interested in the forms and tropes of love in relationship. Is God lover, master, father, mother, friend? King? Hidden yet searchable self? Endlessly unknowable other? And how do the answers to these questions impact relationships on the human scale? What does the Qur’an say about the way we are to be with each other, and how has that manifested across time and place and communities of faith? What is our individual and collective aspiration? How do we make it so?

The creative arts turned out to be an ideal avenue down which to explore these questions, since so many of the responses ultimately hinge upon the act of co-creation. Poets, activists, imams, politicians, rappers, scholars—all had something to say, or show, about creativity. For Iqbal it was change agency, for Mipsterz it was self-expression. The journey of this course was a journey of creative inquiry: into God as creator, the arts as creation, the inner life as source, and the outer life as inspiration.

Here is an overture of how that journey unfolded, theme by theme:

The first and overarching theme was the power of God’s love to unite diversity. It came up almost right away, as Professor Asani introduced us to constructions of Islam and the difference between Islam with a big “I” and islam with a little “i”. This is the focus of my first post. The theme continued to reverberate and gain momentum all semester, as we explored Islamic architecture, calligraphy, music, art, and literature from across time and place. The film, Koran by Heart, was an amazing example of young people from all over the world, and with hugely divergent life experience, coming together to recite the Qur’an. Their diversity was maintained and celebrated, as they each brought something different to the recitation, or Tajwid, but was united by the shared goal of memorizing and recounting God’s word. This mostly-positive example brought some counter-examples into stark relief. Our guest lecture on the Bosnian War was a particularly devastating study of the opposite case: of a wholesale effort to stamp out diversity and impose a standardized worldview, with resultant genocide, horrific violence, and cultural devastation. The example of Saudi Arabia provided a similar contrast, in which the government attempts to control every aspect of Muslim identity and practice.

These examples highlight the fact that, embedded in the theme of unity in diversity, is the notion of unity being different from uniformity: that we do not have to see or think alike in order to be spiritually alike and connected as participants in God’s creation. In my second post, I tried to ground this theme in the power of everyday love as a counter-force to oppressive attempts at uniformity. I tried to show how personal expressions of love, when joined together, are even more beautiful and powerful than when taken alone. This is how I experienced our exploration of Muslim calligraphy and architecture. Each expression was personal, different, and unique, but commonalities and patterns emerged – both within cultures, and across cultures – when they were studied together.

My third post furthers the theme of patterns as a mark of the divine. I was struck by the sheer volume of nature symbolism in Islamic art and especially Sufi poetry, and the debate over representation versus decoration versus something more profound, like pattern as a gesture toward the infinite and unrepresentable spiritual plane. I try to capture some of that conversation in my post. It seems that pattern is an important consideration in fostering religious community. Elements like ritual and tradition are part of what facilitate a sense of unity and belonging, but can also become calcified and rigid. Patterns of conduct and aesthetic, it strikes me, are simultaneously necessary and important to hold in balance with individual initiative. I think of The Conference of the Birds, in which each bird has a different excuse to not to go on the journey. Each one needs to be held accountable to a higher standard of conduct, yet each one is unique and, therefore, must follow a different path to find the divine. But, like us, they are strengthened by journeying together.

This leads me to the importance of devotion in finding one’s personal path toward God. This is the subject of my fourth post, and was one of my favorite lessons in our course. I knew very little about Sufism before this semester, nor did I know the story of Mi’raj and Isra’ in the mystical account of the Prophet Muhammed’s journey to see the face of God. We saw many beautiful artistic depictions of the Prophet’s ascent to the highest heaven, but more importantly for me, this story opened up a portal of possibility for all individual Muslims and, I’d venture, for all individuals who wish to know God. That is the possibility of spiritual ascent – of ascending toward God by living a life the way the Prophet lived. Here again I wish to highlight the interplay of individual devotion and community life. For the Prophet’s virtue was revealed in both his intimacy with God and his service to others.

My fifth post builds on the theme of becoming Godlike by growing in love. I was especially inspired to learn about Pakistan’s national poet, Allama Iqbal, and his vision for actualizing individual potential. With this piece, I wish to highlight themes from the course around the role of nations in the construction of religious identity, and the challenges of growing in love in the midst of international politics that include the use and misuse of authority. To bring back the context of 9/11, it was poignant to read and watch The Reluctant Fundamentalist and to try to make sense of how entire cultures can shift so dramatically based on a single incident, such that an individual like Changez becomes the locus of a whole nation’s fear. What does it look like for Changez to grow in love, to grow toward God, when alienated by those who once purported to love him?

My response to this, perhaps unsurprisingly, is a call to creativity. My final post is a design for sacred space. It is both a reflection on our in-class partner exercise and an invitation to the reader to reflect likewise: What is sacred for you? What is sacred for your friends, family, and loved ones? I hope to provide my own example as an offering to expand the conversation. To learn what is sacred to another person, we need to ask. To learn most anything about another person, we need to ask. I make this case for curiosity because I think that is what is needed to overcome the alienation, phobia, and violence that has come about in America since 9/11 – not to mention, what it will take for each of us to grow in love and toward God. But I will let you read and consider for yourself.