By nature, we struggle to connect with those different than ourselves. Whether we speak a different language, come from a different background, or even just have different preferences, the discrepancies create barriers and tensions between the varying parties that can lead to a variety of results. First of all, the differences can potentially spur conflict through miscommunication and misunderstanding. As the blog shows, the language barrier has the potential to blur communication and meaning, therefore creating conflict where there need not be. However, these differences can also cause heightened discussion and questioning of both others’ thoughts and one’s own.

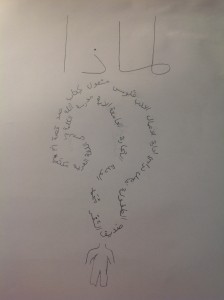

When we are faced with issues or people that we do not understand, an innate curiosity drives us to understand these things, through exploration and communication. The communication barrier is still there, so the answers might be jumbled and incoherent, but the desire to know is still very present. This desire triggers not only the desire to learn about those different from us but also a reevaluation of ourselves and our personal motivations. Granted, the latter does not always occur. Those too insecure with their own culture or background will rather translate that insecurity into indifference towards the other out of fear that the other might have taken a better path. But if one can open oneself to the possibility of immersion and self-improvement, cross cultural exchange can immensely educate and develop our world.

Looking at the issue of language is also fascinating. Referring to the role of the translator, how does learning a new language affect one’s view of the world and the language’s culture? I try to demonstrate that language of course opens up a whole new lens through which to experience foreign culture. Through language, the speaker or listener can grasp the mannerisms, the relationships, and the nuances within interactions. But on the other hand, how does learning a language as a second language affect the impact of these nuances on the speaker, who has already grown accustomed to the nuances of his own language and culture? In my opinion, language is the most definite, tangible aspect of culture. Therefore, one can switch between language and cultures while exhibiting the nuances specific to that language without blurring one’s cultural identities. Not only is it possible to maintain the specific styles of multiple languages and cultures through the differences in language; the differences in language themselves allow for the successful, un-blurred plurality of cultures within one’s identity by creating a clear line between the multiple sides of one’s identity.