“To-day shall the rose be turned out of its delightful spot by the tyranny of the thistle. Dear sister, if any dust happen to settle on the rosy cheeks of my lovely daughter Sukainah, be pleased to wash it away most tenderly with the rose-water of thy tears.”

– Imam Husain in The Miracle Play of Hasan and Husain

In The Miracle Play of Hasan and Husain, Husain says this to his sister who has already begun to mourn his coming death. This line metaphorically addresses Husain’s future martyrdom by drawing on the common symbolism of the rose to represent the Prophet and his family, since the rose is seen as the perfect flower (much like Muhammad is seen as the perfect human). The rose is even said to have been created out of Muhammad’s sweat.

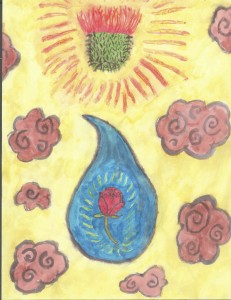

I painted a picture of this metaphor (and along the way discovered how difficult painting with watercolors is). I drew a red thistle at the top, whose prickly nature parallels the animosity of Husain’s enemies (particularly his murderer, Shimr). It is high up on the page to reflect Shimr’s military success, while the rose (the symbol for Husain) is beneath it. While I chose to make the rose red in order to make it more recognizable, I decided to draw the rays coming out of it in green and the rays from the thistle as red. These mirror the colors in Ta’ziyah traditionally associated with Shimr (red) and the Family of the Prophet (green). The rose is in a tear drop, both to visually represent the rose-water used to brush away the brown clouds of dust on Sukainah’s cheeks, but also to represent the tears of the Shii Muslims who mourn Husain’s death at Karbala every year during the month of Muharram.

While the thistle may occupy the “delightful spot” in this picture, stories like Husain’s which depict martyrdom and failure (in this life, at least) are used by Shii Muslims to help them persevere through their historical persecution by Sunni Muslims for their “heretical beliefs.” While the rose may be turned out of its spot, Shii Muslims are assured that their continued faith in their Imam and their form of Islam will ensure that their suffering on earth will not be for nothing.

Recent Comments