Why won’t programmers wear shoes?

I’ve noticed this trend throughout Where Wizards Stay Up Late as well as in my real life observations of computer science majors. There is a peculiar mythology of the iconoclastic genius and his odd but tolerable behaviors.

Crowther insisted on only wearing sneakers. Einstein purportedly never wore socks.

My father, whom I consider to be a genius merely tolerates the bare minimum in grooming and will only ever replace tattered wardrobe staples if my mom and I demand it of him.

While I don’t think that it is coincidence that genius and eccentricity often align, I do find it notable that this particularly archetypal genius is almost exclusively masculine.

There are several reasons I have been thinking about as to why this might be true.

First, women in STEM historically have been barred from collaborative intellectual spaces with men both institutionally and culturally. As such, there are simply fewer notable female scientist who are known much less admired to the extent that their personal quirks are included in the mythology of their academic work.

Furthermore, the association between poor grooming and purported genius is premised on the notion that the pursuit of knowledge is allowed to eclipse the performance of vanity. The belief that “Real Programmers don’t wear neckties” is just one manifestation of this principle.

http://web.mit.edu/humor/Computers/real.programmers

The crux of this notion is societally enforced as inherently masculine. Insofar as women are expected to look a certain way in the workplace to maintain “professionalism” there is no room for a woman’s bare feet to be admired as indication of their intellectual vigor. Recent studies have found that women must carefully gauge their physical presentation through makeup simply to convey (not actually demonstrate) competence.

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/13/fashion/makeup-makes-women-appear-more-competent-study.html

There appears to be a uniquely pervasive bro-ishness throughout programmer culture that is continually reinforced by the individual egos and attitudes of those who hold such opinions and it more widely enforced through a paradigm that both implicitly and explicitly delegitimizes women’s work. However, this was not necessarily true throughout history. Vikram Chandra’s book Geek Sublime explains that the masculinization of the computer industry was a systematized effort that just so happened to end up prioritizing men who preferred not to be bothered with proper grooming (or shoes).

https://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/24/books/review/geek-sublime-by-vikram-chandra.html

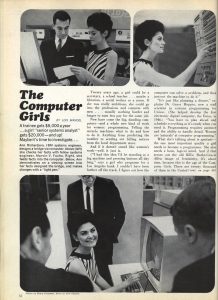

While the role of women in early programming is often ignored or overlooked it was precisely this tidbit of historical precedence that encouraged me to take this class in the first place. In 1967 Cosmo Magazine advertised programming jobs to women by comparing writing code to the familiar domestic trope of planning a dinner. In its earliest conception the majority of coding was done by women. Much like the graduate students who were given the task of writing software, women were tasked with computational coding because their labor was cheaper. However, unlike the grad students whose work would eventually be acknowledged as groundbreaking by even the uninitiated public, the work of these women has been forgotten. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/when-computer-programming-was-womens-work/2011/08/24/gIQAdixGgJ_story.html?utm _term=.7ae4409fd000

_term=.7ae4409fd000

As programming became more relevant and respected, the process for entry became more elite and masculine. Despite this, women like Jean Sammet, who developed FORMAC and played an influential role in the creation of COBOL, continued to participate and contribute to a field where women were systematically underrepresented.

I often think about how culture functions to limit participation or encourage inclusion. I believe we are at the forefront of creating cultural and paradigmatic shifts that prioritize parity and value an egalitarian meritocracy. I like to think that years from now, women will be given credit for and remembered by their eccentric brilliance and their invaluable contribution regardless of whether they wear makeup or shoes or not.

9 Comments