Presidents, Politics, and Fair Use

by Kenneth D. Crews

It’s February in an election year, and that can only mean that fair use is everywhere. It is on the television, in the political rallies, and in the leaks and machinations of governmental grinding. We might often think of fair use as the basis for quotations in books, classroom materials for students, and innovative art and music built on generations of creativity that came before. But fair use is an inherently political creature.

Fair use originated in United States court cases from nineteenth century, and it was enacted by Congress as Section 107 of the Copyright Act of 1976. Getting anything through Congress is of course a political challenge, and every bit of the 1976 law was a belabored exercise that required almost two decades of hearing and compromises before Congress was ready to make the political decision affirming fair use into American copyright law.

Fair use is also political because it represents a policy choice by lawmakers in courts and Congress to allow limited uses of other people’s copyrighted works, taking into consideration variables of fairness, now known as the four factors of fair use. Congress at the same time made the political decision to empower individuals to engage in fair use – to determine what is good and proper as the law directly affects the copyright owners and users – and to evaluate how uses might affect broader public interests and promote the mission of copyright to encourage creativity.

The politics of fair use also has a much more earthy manifestation. As the campaign season becomes more heated, fair use becomes more prevalent. Some uses are surely accomplished by license while other works may not be protectable under copyright at all.

Consider the campaign ad that includes a clip of a presidential candidate speaking pointedly on a CNN program. Depending on the candidate’s exact statements and your point of view, you might want to use that clip in a short TV spot to support or attack this candidate. It matters not whether the speaker is Biden, Buttigieg, Bloomberg, Klobuchar, Sanders, Trump, Warren, or any other election prospect.

Imagine you are the campaign manager for a candidate trying to launch your latest ads, and those several seconds from CNN are perfect. You could get permission, but unless you have a prior arrangement to expedite the process, permission can be fatal. It might never come; it might be burdened with conditions; it might have a hefty fee. Permission can stall the moment, and you are going to miss your constant rolling deadline.

Further, suppose you still want permission; you have to wonder, “Who can grant this permission?” The candidate is speaking her own words; the candidate likely owns the copyright in those words. The CNN crew members are choosing camera angles and developing the layout and imagery on the screen; CNN surely holds those copyrights. Other copyrights might creep into the clip, including quotations, signs, and background music. Theoretically, multiple permissions might be needed for just the momentary passage.

Fair use fills the voids and paves over the uncertainties. Based on the four factors, this campaign use of the clip is highly likely to be within fair use. The election purpose advances the social policy of copyright; the work is fact-based news of great public interest; the amount is minuscule; and the use may well promote CNN and not harm it.

Realistically, this kind of use is also a classic calculated risk. The campaign is in full tilt. The election is on Tuesday. The polling is grim. You’re are holding a prime-time ad slot on the networks tonight. You have to get this great commercial shot, cut, and launched. The risk calculation is more than just wishing for the best or hoping no one notices. The risk is in large part your own determination that a judge will agree that you are within fair use.

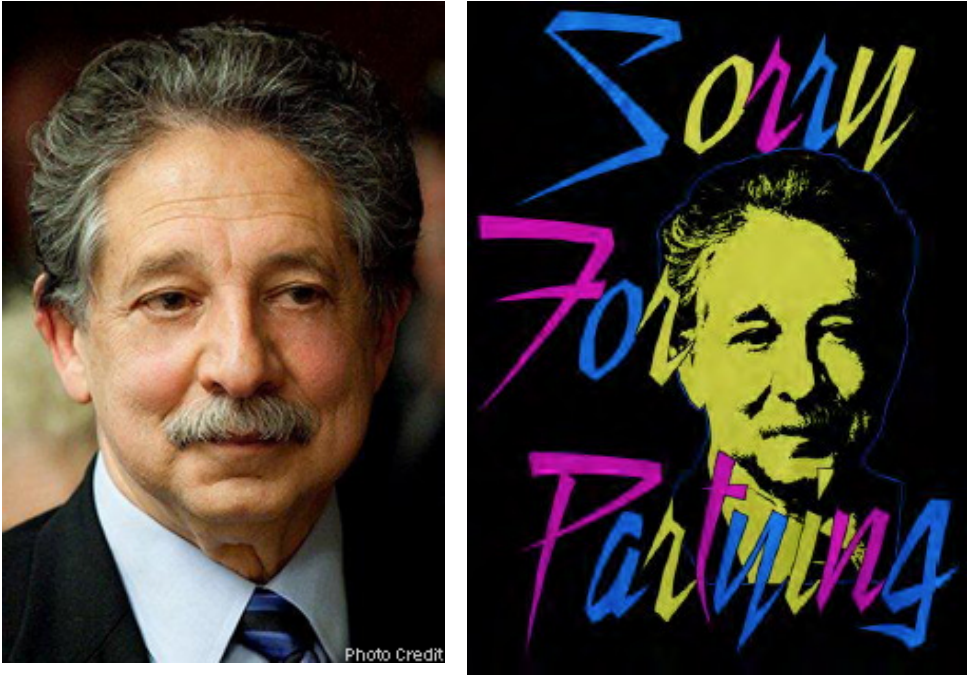

Realistically, these things rarely if ever go to court. In Kienitz v. Sconnie Nation LLC, 766 F.3d 756 (7th Cir. 2014), the court ruled that the makers of t-shirts criticizing the mayor of Madison, Wisconsin acted within fair use when they made transformative use of a photograph of the mayor. Perhaps most important, the use encompassed only a portion of the photograph for a transformative purpose, and the use did not substitute for objectives of the original work. Add the pressured production deadline for a campaign ad and that the candidate’s statements are customary political fodder, and the likely result is a stronger case for the copyright exception.

Instead of going to court, political fair use is usually fought in the trenches among well-meaning and stressed professionals. At the least, they (i.e., their lawyers) should know the fundamentals of copyright and fair use and be ready to assert or respond to an infringement claim. They should also know that sometimes presidential politics is breeding ground of fair use. When Justice Joseph Story developed the concept in an 1841 court ruling, he was deciding a case that involved the published papers of George Washington.

Which takes us to Trump and Watergate. In the thick of the latest impeachment proceedings, John Dean of Watergate fame, was a guest on CNN when the topic turned to leaked excerpts from the forthcoming book by former National Security Advisor, John Bolton. While other guests that day honed in on the formidable political threat, John Dean chimed, “You also have copyright issues here. Start releasing books that are not published.” The rest of the panel hit the boring button and moved on. But Dean was onto something – a fair use lesson from his past life in Watergate.

Dean went to jail in the 1970s. President Nixon resigned. Gerald Ford gave a pardon, and he wrote a memoir. The Nation magazine quoted about 300 words from the then-unpublished Ford manuscript. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1985 that The Nation magazine was not within fair use in reprinting those selected words, from a vastly longer book manuscript, into a critical news report (Harper & Row v. Nation Enterprises, 471 U.S. 539 (1985)). Because the work was yet unpublished, the Supreme Court found that the amount was excessive and interfered with potential sales of the book.

Yes, John Dean, there are “copyright issues” surrounding the Bolton book and the Trump impeachment, especially while the book remains unpublished. However, copyright also offers some solutions. The press can write about the book, without necessarily using Bolton’s expression. Moreover, if publication is stalled or if the public interest escalates, the opportunities for fair use may well expand.

Welcome to the season of fair use. This is the time when fair use fuels elections and news reporting. This is the season which begins to define the perimeter between the public interest and the economic marketplace. This is the quadrennial interlude when fair use blossoms in full and is plainly visible for all to see on the daily news and the pressured campaigns.

Kenneth D. Crews is an attorney in Los Angeles and was formerly a professor of law at Columbia University and Indiana University. He is the author of the book Copyright Law for Librarians and Educators: Creative Strategies and Practical Solutions, available in a new fourth edition launched at the end of February 2020. Download a sample of the new edition and order online.