Hacking Fair Use: Making Music Accessible

by Kathleen DeLaurenti

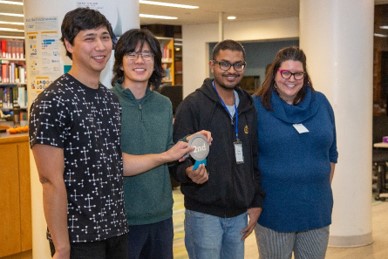

(Photos by Ben Johnson)

When you put music, technology, and one sleepless night in a blender, how do you end up with fair use? This year, some students at Johns Hopkins helped us figure that out!

A new annual tradition at the Peabody Institute, PeabodyHacks invites students to spend 24 hours experimenting and developing projects at the cross section of music and technology. We encourage novice attendees, try to foster collaborations between engineering and music students, and focus more on process and experimentation than sophisticated final projects. The event also allows students to meet guest artists like Laetitia Sonami and Suzanne Kite, whose work challenges ideas of being, femininity, relationships with artificial intelligence, and embodiment of digital sound and physical bodies.

The second Peabody Institute annual hackathon brought to life a slew of interesting projects in January 2020 focusing on music and accessibility. Students created electronic instruments for beginners, developed games to help students with beat-deafness (it’s a thing!), and, to my delight, made music more accessible with fair use!

Ankur Kejriwal, Dylan Lewis, and Winston Wu are students who, during their day jobs, study engineering and computer science. As serious amateur musicians, they wanted to develop a project that made music more accessible for musicians who were still developing their chops and might find sitting down at the keyboard to play their favorite music intimidating. Semplice, their music simplification engine, allows anyone to take their favorite piece of music and make it easier to play without losing what they love about the piece.

Ankur Kejriwal, Dylan Lewis, and Winston Wu are students who, during their day jobs, study engineering and computer science. As serious amateur musicians, they wanted to develop a project that made music more accessible for musicians who were still developing their chops and might find sitting down at the keyboard to play their favorite music intimidating. Semplice, their music simplification engine, allows anyone to take their favorite piece of music and make it easier to play without losing what they love about the piece.

The premise behind Semplice is, well, simple: a user uploads their copy of their favorite piano piece that is too hard to play, and chooses how to make it easier. They can eliminate all 16th notes so that they don’t need to play as fast, simplify the left hand, or turn the left hand playing all into chord blocks. While simplifying the left hand makes it easier to play, it also allows for harmonic analysis of piano music, which can be beneficial for music theory students or anyone who might want to learn more about arranging and improvising.

Once you’ve selected how much easier to make the piece, then the magic happens! After quickly processing it through an OMR engine (optical music recognition), users get the new version of the piece to download and perform for their own study and personal use. Or, as I like to think of it, musical fair use magic!

When I reached out to the team after their 2nd place finish in the hacking competition, they were surprised that fair use had anything at all to do with their work. They had some experience with music copyright as music lovers: Winston Wu shared that he often buys transcriptions of his favorite symphonic works to play on piano, his main instrument. But when they were developing Semplice, they hadn’t spent a lot of time thinking about copyright.

The simplicity of the project is also what makes it such a wonderful example of fair use: users upload copies of music that they already own and only the uploader gets the simplified, derivative version. Speaking with Ankur Kerjiwal, he notes that even the processing logs don’t tell you anything about what pieces were uploaded and processed. You can see what someone named their file, but no user info is collected during the process, so the metadata in the logs doesn’t tell much of a story at all. The team is currently considering how to make the engine available, but they envision it as a free, light weight tool that solves a specific problem without copying, distributing, or making additional copies of the music available.

In conversations with Ankur, even though the team wasn’t thinking about fair use this time, copyright and fair use often create a “road bump” in his work. He relies on large datasets for testing his software projects and, as a PhD student, he needs to be able to publish that data openly to have his work peer-reviewed. While some of us who frequently work on copyright might think that the Google Books case settled the issue of computational data, it’s complicated, especially with music and websites who have restrictive terms.

I asked Ankur about his experience using the widely available musiXmatch dataset that is part of the Million Songs Dataset project. Because of copyright and other restrictions, less than one third of the million songs data lyrics are included. Also, to side-step concerns about the dataset, the research team has released the set as bag-of-words data, meaning that you don’t get the collected lyrics for each title, just counts of words across the dataset. I asked Ankur if this limited the utility of the dataset. He said, “Absolutely – you would be able to do much more if the set included full lyrics in the order they appeared in a track.”

Music continues to bring us its share of fair use challenges, but it’s exciting to see young engineers wading into the fair use waters. Uncovering unwitting fair uses in our campus community has proven a great way to educate faculty, students, and colleagues about how to flex their fair use muscle. With resources like our copyright consultation service at the Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University, I hope that we can continue to work with students to help them take advantage of their fair use rights so that they can make music, accessibility, and magic happen.

Kathleen DeLaurenti is the Head Librarian at the Arthur Friedheim Library at the Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University. Her work includes publishing projects for music, teaching music-focused copyright, and advocating for both fair use and the public domain. She has been active in the Music Library Association (MLA) Legislation Committee as a member since 2009 where she has also served as chair of the Best Practices for Fair Use in Music Collections task force. She has also been a member of the Copyright Education sub-committee of the American Library Association (ALA) and is the 2015 winner of the ALA Robert Oakley Memorial Scholarship for copyright research.