I am delighted to present the third day of the 10th Anniversary of Fair Use Week with a guest post by copyright expert Sandra Aya Enimil from Yale University. In this post Sandra explores a bit of the pending Warhol decision through the lens of the subjects that may not always have rights in images that contain their likeness. -Kyle K. Courtney

Who Owns My Image? – A Fair Use blog about a Fair Use case (But this blog is not totally about Fair Use)

by Sandra Aya Enimil

It’s Fair Use Week and I was asked to write about a Fair Use topic, which I have done (here and here) for a few years now. This year though, I want to write about an issue that I have been thinking a lot about and it is related (tangentially) to an important Fair Use case on the minds of many. For this Fair Use Week 2023 blog , I am not fully discussing Fair Use, I want to discuss pillars of copyright law, and incredibly the important elements of fixation and ownership.

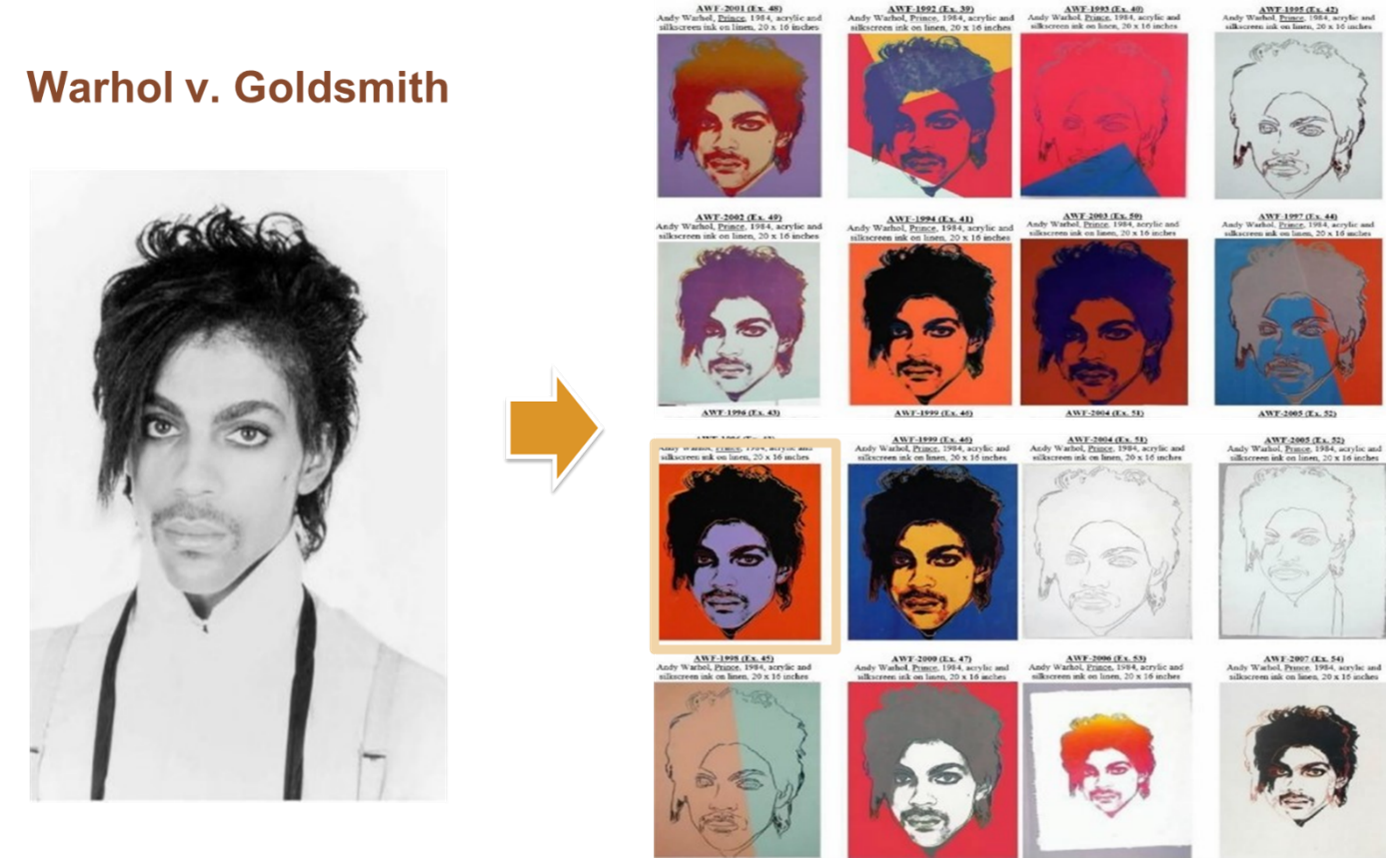

Many people are following Warhol v. Goldsmith, which was heard by the United State Supreme Court in October 2022. The case results from a dispute between the two artists, Andy Warhol and Lynn Goldsmith over a photograph of another artist, Prince. Goldsmith is the original artist; Warhol received a copy of the image and created variety of colorized and enhanced versions of the image. Warhol, and later his estate, sold originals and prints of his versions of the image. We now await a decision from the Supreme Court on whether Warhol’s use is Fair Use. There’s no doubt that a determination of what is transformative Fair Use is the main issue at play in this case.

The photo on the left was taken by Lynn Goldsmith and was licensed by Vanity Fair. Vanity Fair provided the image to Andy Warhol who then created the series on the right. The highlighted Warhol image was used in article after Prince’s death.

While I am curious about the forthcoming decision, something about the case had been bugging me and could not articulate it until I viewed a panel presentation from Professor Emily Behzadi about Warhol hosted by Jeffrey Prystowsky at Roger Williams University School of Law. Behzadi spoke about Prince as the subject of the photograph and the center of the controversy, but not one with the power of a copyright.

Her presentation made me recall another panel presentation by Professor John Tehranian on a similar theme: cultural appropriation. Behzadi and Tehranian discuss race and gender implications regarding copyright authorship and the lack of copyright interest in images in one’s own likeness. In photography, the person who snaps the photo, paints the portrait, who fixes the image in a tangible means of expression, is the copyright owner. In Warhol, Prince, or a representative, likely signed away his claim for any and all rights in the images taken by Goldsmith. While copyright was probably listed among the disclaimed rights, currently, a subject of a photo would typically never be considered a rights holder of the image unless they took the photo (selfies anyone?). Goldsmith was and is the rightsholder of the images she took of Prince. The Warhol Foundation is making a Fair Use claim for the creation of the Prince series. Why doesn’t Prince, or now his estate, have any claim?

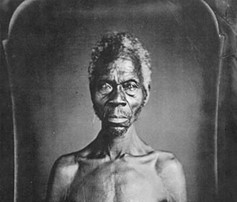

The interrogation of the assumption that subjects should have no interest in photographs is longstanding. A recent case, Lanier v Harvard, where the descendant of enslaved persons in a photographic collection[1] sought redress for use of the images, continued the conversation about the rights, not just of subjects, but of their descendants.

The descendant, Tamara Lanier, initially brought, among several claims, a copyright property interest claim. This claim was not allowed to move forward due to the issue of authorship and ownership (in June 2022, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court allowed the case to proceed on a claim of emotional distress.). The photos were commissioned by professor and known white supremacist, Louis Agassiz on behalf of Harvard University. Harvard owns the copyright. The subjects, include ancestors of Ms. Lanier, Papa Renty and his daughter, Delia, had no property interest as subjects. Further as enslaved individuals at the time, they had no rights around consent or any other non-copyright rights photographic subjects might expect.

Attorney Josh D. Koskoff, left, Tamara Lanier, and Attorney Ben L. Crump, right. Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court in Boston, November 2021. Photo by Raquel Coronell Uribe: https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2022/6/24/lanier-supreme-court-remanded/. Edited photographs of Delia and Papa Renty.

There’s also been engagement on social media, fascinatingly, on this issue as well. Consider the Twitter thread below by Dr. John Mason. Mason focuses on the person who is subject of the photograph and their agency, or not, in being photographed.

What would photojournalism & documentary photography look like — now & in the past — if the photographer's right to take someone's image were balanced by that person's right to say No?

— John Edwin Mason (@johnedwinmason) December 29, 2020

The photographer's right to take has been & is rooted in a connection to power–cultural, economic, political. The poor, the marginalized, & the oppressed have never had a parallel right to refuse to have their image taken because they lack & have lacked that connection to power.

— John Edwin Mason (@johnedwinmason) December 29, 2020

Say her name: Florence Thompson. When the well-dressed government lady in the big car stopped & asked if she could take her picture, she was in no position to refuse. She became the iconic face of the Great Depression, & she resented it. (Photo: Dorothea Lange/FSA) pic.twitter.com/pPxzsxcu67

— John Edwin Mason (@johnedwinmason) December 29, 2020

"I wish she hadn’t taken my picture. I can’t get a penny out of it. [Lange] didn’t ask my name. She said she wouldn’t sell the pictures. She said she’d send me a copy. She never did." https://t.co/7djZTLJvdD

— John Edwin Mason (@johnedwinmason) December 29, 2020

Actress and model, Emily Ratajkowski, echoed the sentiments of Florence Thompson, wondering why she, as a subject voluntarily or involuntarily, had no rights in images that contain her likeness. As with Prince, Ratajkowski likely signs releases for her commercial work as a model[2] and as a famous person, she is the subject of many photos where no permission is sought. She has even sued by a photographer for reusing an image of herself on her own social media page. Why can’t she have a copyright interest in the images of herself?

So, what is the solution? Should the person in the photo have rights in the image just as the person who created the image? Or perhaps following copyright considerations for oral history interviews, where the interviewee and the interviewer could both contribute copyrightable elements, should there be a joint or split copyright? Should we add a copyright interest for the subject of photos?

Many copyright scholars lament adding more rights to copyright law, arguing that copyright cannot be expected to “do it all.” In 1865, the category of photography was added to works that could be copyrightable[2] in the United States.[3] Forty years later audio-visual works (like motion pictures and films) were added. We have continued to add categories and refined definitions of author/creatorship, why not add another thing, a right for persons who appear in copyrighted works?

I can hear my copyright colleagues and researchers screaming at their laptops, “how is that going to work!?” I have no idea, how does any of this work?[4] But I do know, if a copyright interest for subjects in copyrighted works were added, Fair Use could apply to those copyrighted works.

Sandra Aya Enimil (she/her) is the Program Director for Scholarly Communication and Information Policy at Yale University Library. At Yale, Sandra provides strategic insight on licensing, scholarly communication, Open Access, copyright, and publishing issues. She is the Chair of the License Review Steering Committee and provides consultation on licenses of all types for the library. Sandra also provides information and resources on openness, Open Access, using copyrighted materials and assists creators in protecting their own copyright. Sandra collaborates with individuals and departments within the library and across campus. Sandra is committed to diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) and is interested in the intersection of DEI and intellectual property.

This blog is cross posted on the Conversations on Copyright at Yale Library Blog: https://campuspress.yale.edu/copyrightconversations/

[1] Carrie Mae Weems appropriated the images of enslaved people from the Harvard Archives in her artwork. Harvard later threatened a lawsuit, Ms. Weems felt her use was a Fair Use said she welcomed Harvard to continue the conversation in the courts. Harvard acquired the artwork. https://legalleft.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/11/2014/07/Murray.pdf

[2] Ratajkowski disputes signing a license for a photoshoot for a certain magazine, the photographer has since released multiple books using photos that were not used for the magazine. Ratajkowski considers those photos to be unauthorized use of her likeness

[3] There was a lot of debate about the creativity involved in mid-19th century photographs.

[4] In Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony (1884), the Supreme Court confirmed that the U.S. Congress had the right to extend copyright protection to include photography: https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/111/53

[5] Basically we made up these laws, why not make up a few more?