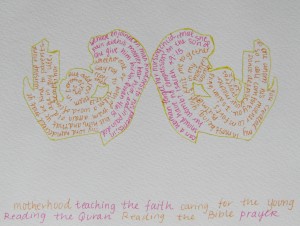

Muhammad and the Rose

March 22nd, 2016Reflection on Suleyman Celebi’s Turkish poem, Mevlid- Serfi (Week 4)

Upon reading this poem I was

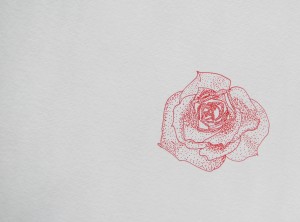

confused by the exalted theology of Muhammad. I was unable to account for the dissonance that verses such as, “since Muhammad is cause of this existence, with simple hearts petition his assistance,” and what I conceived of as a strict ideology of Monotheism, which existed in sharp contrast with fear of shirk (Chelebi, 18). My confusion wasn’t eased when I came across equally extravagant exaltations of Muhammad, such as “whose light did make the whole world shine in brilliance, whose rose-like beauty filled the world with roses” (Chelebi, 25). This confusion demonstrated my lack of understanding about the role of mentorship and potential for emulating the perfection that Muhammad represents in many Muslim contexts.

I’m intrigued by this verse employing the imagery of the rose because there is something contagious about Muhammad’s beauty, which enables him to fill the world with roses. Yet, his beauty is not that exactly aligned with that of the rose, but rather, something “rose-like.” This distinction is indicative of Muhammad’s distinction, as the last embodiment of the Divine Light, and there is almost something otherworldly about him, despite his fully human existence.

The comparativist in me cannot resist recalling the fact that Mary in the Christian tradition is also associated with the rose. I am intrigued by the association of the rose, which many consider to be the most beautiful or perfect flower, and these two religious figures. I think an analogy will concisely sum up my musings.

Muhammad: The Qur’an :: Mary: Jesus

Both Muhammad and Mary are the means by which the divine is manifest in the world. Both are the vehicles through which God exercises Her will. It is at this point that I recognize my lack of knowledge about the doctrinal presence of free will in the Qur’an and in Islamic traditions. I am tempted to say that both Mary and Muhammad are deemed as exceptional, perfect, rose-like beings within their respective traditions because of their willingness to submit their wills to the will of Gods. While I do not know the explicit teaching on this subject from as rooted in Islamic tradition or the Qur’an, I do recall one of the main messages from Muhammad’s Mi’raj, and that was his shift from ego-centric to God-centric. This, in conjunction with the fact that Muslim literally translates as “one who submits,” makes me inclined to think that this hypothesis is plausible.

Posted by julierel

Posted by julierel