Introductory Essay

ø

Introductory Essay: Beauty, Spirituality, and Inclusiveness in Islam

In my collection of creative responses, I have chosen to explore a wide range of ideas surrounding the religion of Islam. Multisensory Religion introduced me to many important notions about the philosophical, spiritual, and artsitic nature of Islam, as these kinds of understandings were emphasized over a doctrine-based approach to the religion.

Subjective thoughts, ranging from the definitions of words and actions like “muslim” and “prayer,” to whole concepts, like god, beauty, nature, and spirituality, were extensively explored. The conversations surrounding these ideas were absolutely fascinating; throughout the class, I was pleasantly surprised to find myself thinking about the otherworldly, the ethereal, the metaphysical aspects of life and humanity. Furthermore, after examining the differing approaches taken by a wide range of communities and countries with varying cultural, geographic, and historical backgrounds, I felt enlightened in my overall understanding of Islam.

These kinds of ideas were so beautifully observed through art. The class explored architecture, music, poems, prose, and visual arts, which aesthetically examined the political, social, historical, and spiritual aspects of Islam. I found myself very moved, particularly, by the art, poetry, and discussion surrounding Sufism and its implications. The ideas of intangible languages coursing through the veins of the world and humanity, and their relationship to the human condition, was so intellectually and emotionally engaging for me. Thus, I have chosen to focus many of my pieces on Sufi ideas, heavily indulging in the allure of abstract.

Generally, my collection focuses on these spiritual, mystical ideas of Islam that are sometimes hidden from the outsider’s perspective of the religion. Codification of Islam, overtime, has cultivated some political and social controversy surrounding the religion, which I reference periodically throughout my collection. However, my aim was, rather than to explicitly discuss such controversies, to focus on those aspects of Islam that were moving to me–the artistic and spiritual basis of the religion.

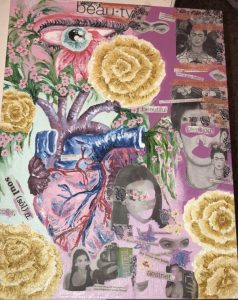

One of the major themes I chose to focus on was the idea of beauty in Islam. The emphasis on aesthetics in the religion was something I had never heavily considered until entering this class, even having taken many art history classes, featuring Islamic art, in the past. I realize, now, that Islamic art is not just a method through which to observe the religion, but that, in many ways, it is essential, and inherent to, the religion. Aesthetic beauty is seen as divine: Allah as beautiful and loves beauty. Beauty thus becomes central to understanding Allah and oneself. My largest peice, the oil painting/mixed media collage, is meant to illustrate certain concepts which help to collectively constitute this conceot of beauty in Islam. It references the physical senses, the beauty seen in the natural earth, and God’s presence in nature. It references, with the central position of the anatomical heart, the important Islamic notion of Ishan, the idea of becoming a beautiful person and embarking on a spiritual quest for internal beauty. This implies a fundamental morality as characteristic of the human search for beauty.

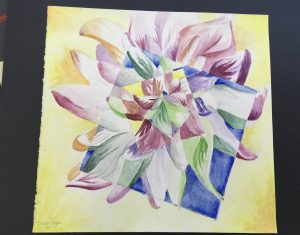

Directly related to this notion is the sub-notion of God’s presence in nature, which is also heavily focused on in my collection. The watercolor piece featuring a flower is my most direct attempt to illustrate this concept. I attempt to communicate, with abstraction of color scheme, the notion that nature, although sensible in the objective sense, is also permeated with more obscure, mystical ideas. In Islam, humans are able to identify, appreciate, and engage in the beauty of nature, and yet unable to completely understand the entirety of the hidden spiritual reality underlying all that there is. Still, I maintain a geometric composition, referencing the Islamic idea of laws which govern the world as proof of divine creation.

With the emphasis on aesthetics comes the discussion surrounding the role of the artist in Islam. In many cases, art is people’s primary method of engaging with the religion. Again, we see the essential nature of it, cross-culturally; artistic venues are places of peace despite that they are enjoyed by people from many different backgrounds. Two particular art forms, the Sufi art form known as Qawwali poetry popularly practiced in India and Pakistan, and the Ghazal form of Arabic poetry, are focused on in my prose piece. The Qawwali style is founded on the idea of poetic verse as a gift from God, positioning it as divine, and resulting in the reverence of many Qawwali writings being equal to that of scripture itself. The idea of Islamic art often permeating the hearts of its audience was something I was moved by, which is why I chose to write this piece. Thus, my prose attempts to discuss the underlying purpose and effects of Qawwali and Ghazal, that is, leading listeners to states of religious ecstasy, and eliciting some kind of internal shift within them. The piece references the themes within the poetry, especially the theme of love, and the way in which this poetry is regarded by listeners/audiences.

Art and politics are undeniably inseparable, which is not necessarily a negative thing. This semester, we saw how artistic engagement with controversial political ideas, like codification, prophethood, womens’ rights, and the role of religion in government, was extremely powerful. Thus, a few of my pieces attempt to illustrate more politically based discussions. For example, my sketch of the arabic word for “music,”موسيقى, attempts to illustrate the controversy surrounding music as an aesthetic in Islam. This controversy, then, begs questions surrounding where lines should be drawn in terms of what should be interpreted as “music,” and what should not, and what constitutes “music,” and what does not. This controversy can involve its denouncement by certain groups, such as, for example, the Chishtis, whose attacks on qawwali are based on the claim that music is inherently wrong. The overall controversy surrounding this argument in general is thus illustrated by the red question mark, central to the piece.

Additionally, I also attempted to examine the role of the prophet in Islam with my other calligraphic sketch, featuring a central word, prophet, surrounded by many more, smaller calligraphic copies of the same word. The fluidity and inclusiveness of Islamic recognition of different important historical figures as prophets and/or muslims (small “m”), is very important. The terms “prophet” and “muslim” are much more broad than they are ofte n percieved; figures like Abraham, Moses, and Jesus are recognized, not as rivals of Muhammed, but as members of the same fraternity, greatly revered by Muslims. The idea of a muslim, originally, was simply meant to refer to someone who “submitted” themselves to God. The term prophet included “messengers” of many nations and cultures, all of whom are thought to be descendents of the same family, all having inherited the same divine light. The representation of this light takes many forms; in some paintings we saw a fire or an orb behind Muhammad’s head, or we saw Muhammed represented as a lamp, for example. The idea is that the inheritance of this light signifies each prophet’s having been chosen for a divine purpose, and all being part of the same fraternity, influenced my choice to include a lamp in my drawing. Thus, I illustrate this inclusive nature, the Islamic notion of imitation of the prophet, and the idea of the passing-down of the prophethood. This, as well as the extent to which Muhammad should be imitated and what should be executed volunarily versus obligatory, are central points of controversy characterizing the Shi’i-Sunni partition. In Shi’ism specifically, the notion that faith in God is incomplete without faith in Ali is essential, as religious authority is then designated for the descendents of Ali. Love and devotion to the family of the prophet Muhammad (to Ali and Fatimah) is emphasized. Much of the prophet-centered art observed in class, including paintings, poetry, and prose, was centered on these figures.

In some cases, I was faced with a decision about which doctrine/sect of Islam to draw themes from. One piece in particular which I struggled with, in this sense, was the poem I wrote surrounding the Shi’i ideology about inability of humans to guide themselves in their spiritual journey. I chose to describe both characteristics of the ideology, and to reference controversies about it. I wanted to draw upon the idea that peoples’ initial connection to Islam is often established through sheikhs, or other holy figures, whose role is not necessarily to preach, but rather, to bless and give advice to people (much unlike the Christian missionary, whose aim is to spread their beliefs). Misconceptions about the similarities of the roles of missionaries and Sufi teachers thus may arise from the fact that both are associated with travel, as the traveling of Sufi teachers was the predominant role of the spreading of Islam throught the Trans-Saharan trade route. I reference the human’s entrance into a spiritual journey to selflessness, the spiritual guide, and the “tariqah,” or “path” to ego transformation. I focus on the notion of selflessness, and the state of intoxication, which are often referenced in close relationship to one another: with genuine, true love of God, there is no longer any fixation on the self.

The poem also, however, also briefly references specific aspects of the history of poetry. This includes the talismanic/healing powers that are sometimes believed to be possessed by poetry, as well as the political history of poetry. The rivalry that emerged between respected poets and Muhammad when Muhammad began to recite his revelations is representative of the roots of much of the controversy surrounding Islamic art.

My overall goal with my collection was to communicate the the essential role of art in Islam, and this role as representative of its spiritual, extremely inclusive nature. Upon examination, we find that this is an important, fundamental idea. For example, when we examine Qur’an recitation, we see that it began as a fluid, subjective, varying method of expressing and engaging with the Qur’an. It was overtime, with institutionalization and codification, that political and religious elite introduced a particular framework for Qur’an recitation–that is, rules and regulations were introduced. Thus, the nature of the codification of the Qur’an is extremely important to understand from a historical perspective. What began as a fluid, fragmented collection of smaller-scale revelations became fixed and arranged into chapters and verses with titles, which had complex effects, including the domination of writing culture as opposed to oral culture, the emergence of Ulama, specialists in the exegesis of text, and the subsequent use of Islam to further political agendas of the state. Directly related to this historical phenomenon of Quran codification is the concept of the Hadith, which involves the chains of transmission (Isnad) surrounding certain ideas. The methodology surrounding Hadith and Isnad can become quite complex, as are the specific details of the authentication process, and the conversation surrounding what kinds of qualifications a person should have in order to authenticate a particular idea.

Also a result of the codification was the crystillization of the six ideologies of Islam, which took place over a very long period of time. For the first three centuries after Muhammad’s death, the conception of who held claim to religious authority was highly ambiguous, resulting in the emergence competing claims in different communities, as well as a new political dynamic in which religion and state became fused. This association of political and religious authority is unavoidable today.

Ultimately, with codification, arose many political controversies that are associated with the religion today. The ideas of art, beauty, and spirituality as central to the religion become lost in this negative perception that people tend to adopt. Thus, I chose to make these ideas the focus of my collection, as these ideas were often the focus of the art observed in class. We looked at Qawwali and Ghazal, at ginans, devotional hymns of the Ismaili Shia community of South Asia, and at didactic songs called qasidah modern, which draw influences from the rhythmic form dangdut, and melodies from Arabic pop songs. We looked at different visual artistic trends, such as the iconoclastic controversy, examining post-iconoclasm depictions of the prophet; we examined different aniconic representations, like calligraphic representation (Hilyaas), figural representations with the face of the prophet left blank, and poetic representations. The emergence of these different aniconic, artistic representations of a previously iconically represented figure in response to the iconoclastic movement, as opposed to a direct decline in artistic practice itself, is fascinating, and demonstrates the essential role of the arts in islam.

The implications of this variety in Islamic art are critical; with multiple acceptable approaches to devotion comes, again, one of the central ideas communicated in this course: the inclusivity of Islam. Engagement with the religion is a personal, spiritual journey and is thus highly objective.

This class demonstrated to me that, when political controversy and strict boundaries characteristic of doctrines are focused on, it is difficult to understand the roots of the religion. Its inclusive, artistic nature, is lost. With my collection, I hope to demonstrate my new understanding of the religion as a fundamentally artistic one.