Prologue

ø

Emmanuel D’Agostino

AIU 54

Creative Portfolio Prologue

TF: Ceyhun Arslan

In an ideal world, a class entitled “For the Love of God and His Prophet: Religion, Literature, and the Arts in Muslim Cultures” would be about just that. It would seek to, as its my.harvard.edu course description implies, examine the relationship between literature/art and religion in a variety of predominantly Muslim cultures around the world, from those geographically near to Islam’s founding to those far from Saudi Arabia, and compare and contrast its findings about those cultures with an Islamic lens. Consequently, this course’s readings would give examples of song, poetry, theater, visual art, music, dance, literature, and the like in a variety of Islamic worlds, showing the breadth and depth of Islamic culture across the globe.

Yet it is a regrettable, if undeniable, twenty-first-century fact that any serious discussion of Islam must speak to the events and the legacy of September 11, 2001. On that day, of course, a small minority of extreme fundamentalist Muslims, representing and speaking for only the tiniest fraction of contemporary Islam, hijacked planes and crashed them into New York City’s World Trade Center, killing three thousand innocent people. As a result of the largely white, non-Muslim backlash to this extreme fundamentalism, Muslims and people who appear, to bigoted eyes, to be Muslim have faced extreme persecution since. Professor Ali Asani’s book Infidel of Love addresses this phenomenon in an interesting and important manner.

While a class such as AIU 54 must mention the events and aftermath of 9/11, which is almost always implied or alluded to in discussions about Islam and Islamophobia, it also serves as a potent weapon against the hatred of Muslims that 9/11 engendered. By spreading the truth about the beautiful, intricate variety of the Muslim world and its culture, and utilizing Professor Asani’s “cultural-studies” approach, which seeks to attribute beliefs and events normally linked to religion to existing cultural and non-religious factors, AIU 54 serves as a tool against Islamophobia and religious illiteracy.

As a result of this dual nature of AIU 54, my creative portfolio seeks to enhance the religious literacy the class spreads by examining various cultural works of the Muslim world from a variety of places and reflecting on them through a variety of media, and, where applicable, linking this back to promoting the truth about Islam as not inherently violent, and often very peaceful and pluralist. I do this by looking at everything from calligraphy to rap, from hundreds of years ago to the present. In reflecting on these pieces, I use four types of media: three drawings in pencil, one in ink, one written rap, and one auditory work. I hope that ultimately, I have used my work to counteract Islamophobic sentiment in some small way, as AIU 54 itself does so well.

In this spirit, my first piece is a visual reflection of Al-Ghazali’s rules for Qu’ran recitation. I use ink, in which many copies of the Qu’ran are written, and I draw a ten-step guide to reciting the Qu’ran in the way he specifies, including everything from crying to reciting a certain number of times per week to specifying the direction one should face. This piece does not follow my anti-Islamophobic mission all that directly, but rather shows an example of the diversity of belief within the Muslim world. Important to note is that while some of Al-Ghazali’s guidelines may seem esoteric or unnecessary, such as dividing the Qu’ran into exactly seven parts or specifying what one should say before and after recitation, none of them are violent or anti-Western at all. Of course, Al-Ghazali’s interpretation does not represent Islam at all times and in all places, but rather one man’s view in one time and place. My remaining pieces look at very different views of Islam in very different contexts, yet they all have a non-violent ethos in common.

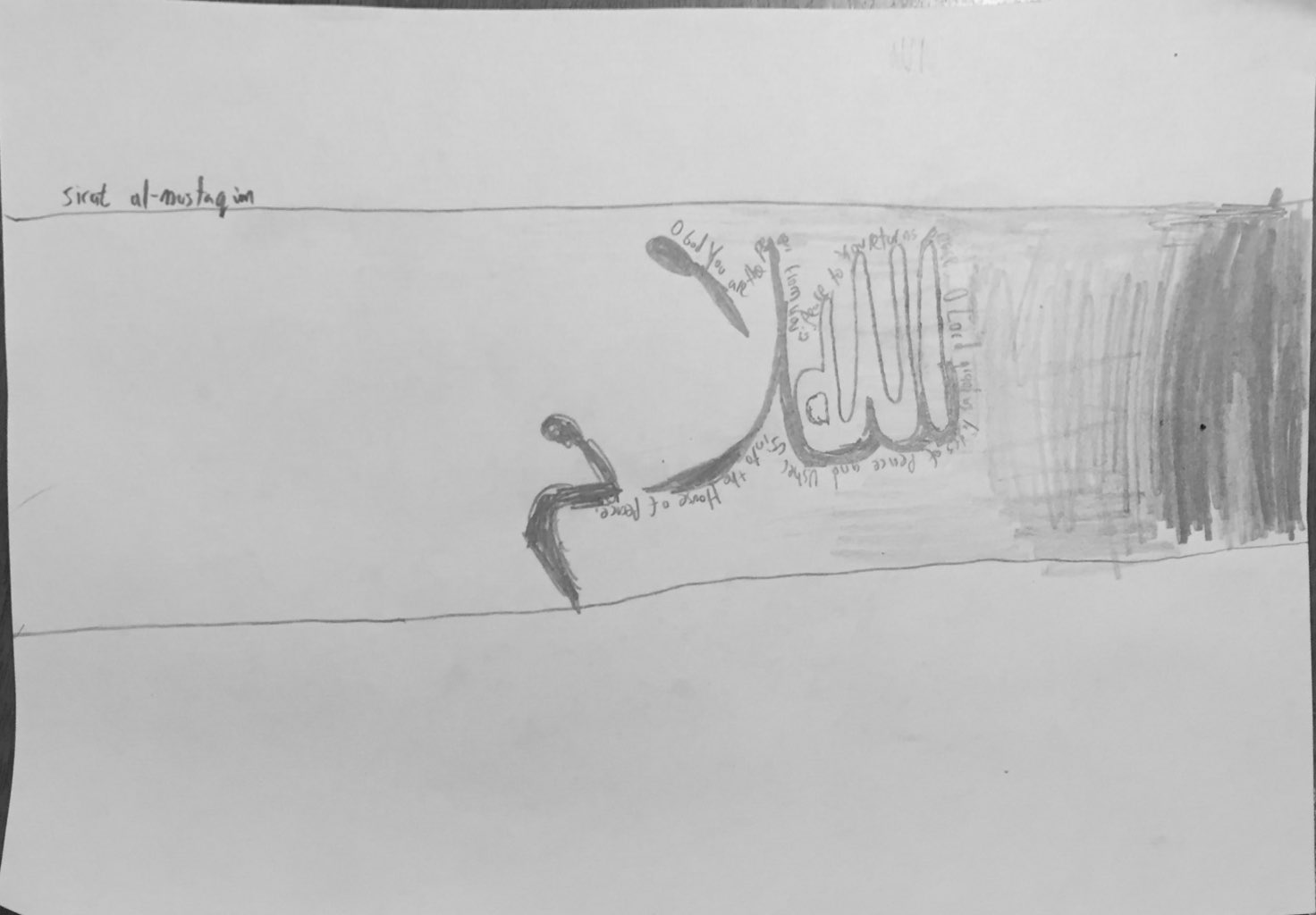

My second piece more directly portrays Islam as peaceful, through calligraphy. Calligraphy has been considered a sacred way to express devotion to Allah by writing the characters of his name. I visually intertwine the characters for Allah with those for the Arabic word for peace, salaam— it was surprising to me how easily they physically fit together. I did this to physically show the connections between God and peace in Islam (which, after all, is related to the word salaam itself). In fact, when God’s beautiful attributes are listed, peace is often near the forefront of the list. I also included the straight path, or sirat al-mustaqim, that God is said to lead his followers on, toward peace and light and away from darkness. Also, calligraphy is only embraced by some Muslims, and its mystical attributes are evocative of the mysticism that characterizes the Islam rejected by those fundamentalists whose actions engender so many misbeliefs and prejudices about Islam at large.

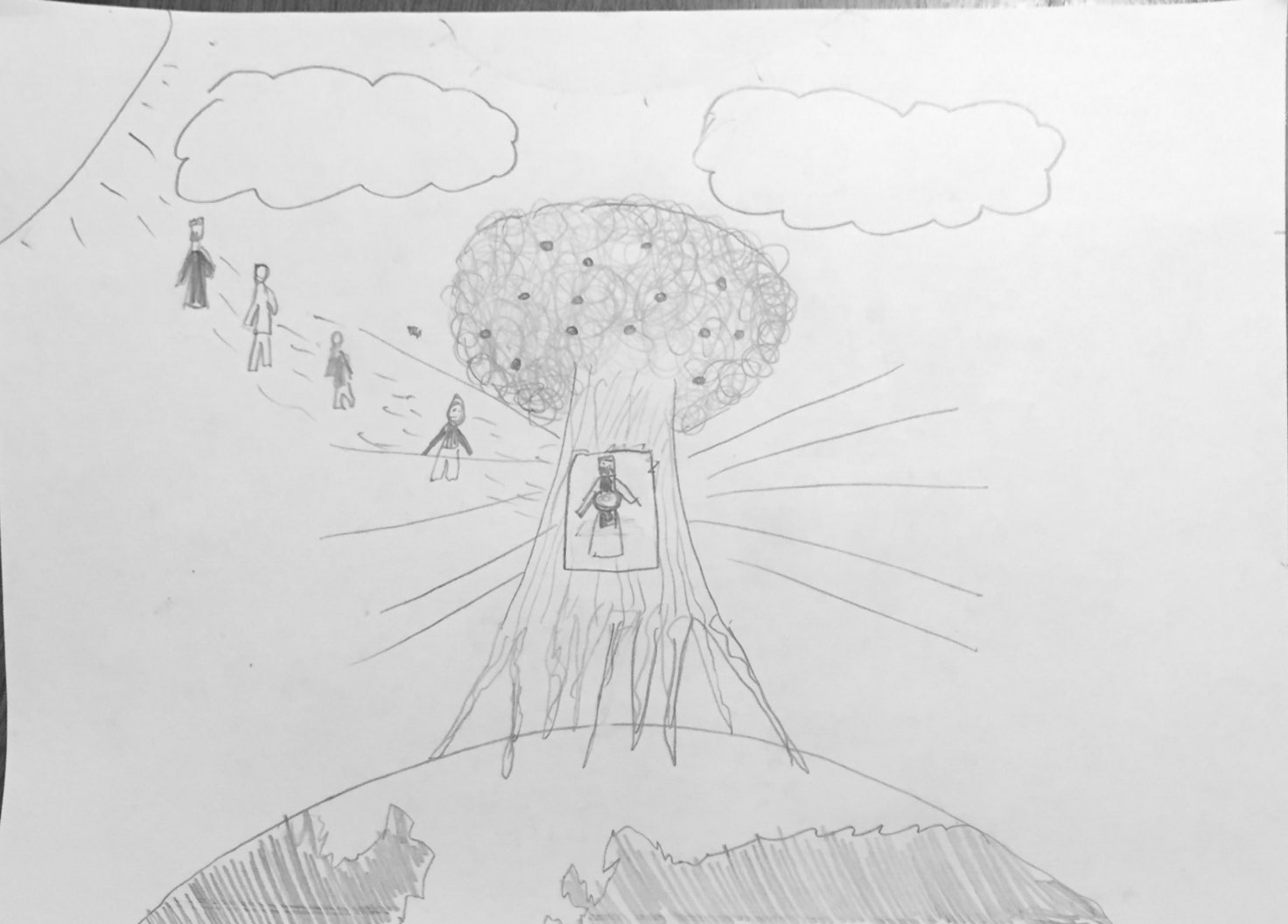

My third piece attempts to counteract Islamophobia and misconceptions about Islam by pointing to some of the pluralist aspects of that religion. The Qu’ran’s “light verse” is well-known, which is a reason I decided to illustrate it here. Somewhat more esoterically, the scholar Mutaqil ibn Sulayman and his followers believe that the “prophetic light” that Muhammad is seen as possessing was handed down to him from a series of prophets, including Adam, Moses, Jesus, and others in the Judeo-Christian tradition. Admittedly, the light does stay with Muhammad, but I really liked the pluralist idea of it being passed down from prophets from other religions. As I mentioned in my commentary on my art, I like how this speaks to my own religious background, not only linking together my Jewish mother’s and my Catholic father’s traditions, but linking them both to Islam. Admittedly, this pluralism is limited, as it only extends to Jews, Christians, and Muslims, or People of the Book (al-kitab) but I still think it serves as a powerful counterpoint to the tiny fraction of Muslims who see their specific Islamic ideology as the only permissible religion.

My fourth piece serves as a personal reflection and response to some of the Islamic hip-hop we read about in section. Hip-hop is seen in many ways as uniquely American, but some types of it also have a strong connection to Islam and to directly counteracting Islamophobia. I think this implies a connection between America and Islam that runs directly counter to the American Islamophobia in our post-9/11 world. Therefore, while I was pleasantly surprised to hear about Muslim rappers counteracting Islamophobia, it made me wish that there was more of a response– I know of no non-Muslim American rappers reaching back out to the Islamic rappers to work together against Islamophobia. This void was what I sought to fill by writing this rap. In it, I write of how, yes, the events of September 11 were horrific, but that they serve as no excuse for the rampant and irrational hatred of Islam that too many Americans hold. I truly believe that while rap is a great vehicle to fight Islamophobia, Islamophobia cannot be eradicated or even minimized through the efforts of Muslim rappers alone. Instead, Muslims, non-Muslims, Americans, and non-Americans must all come together to fight against the irrational fear and hate too many non-Muslim Americans hold. I think that my rap, rudimentary as it may be, is an important first step toward fighting Islamophobia through music.

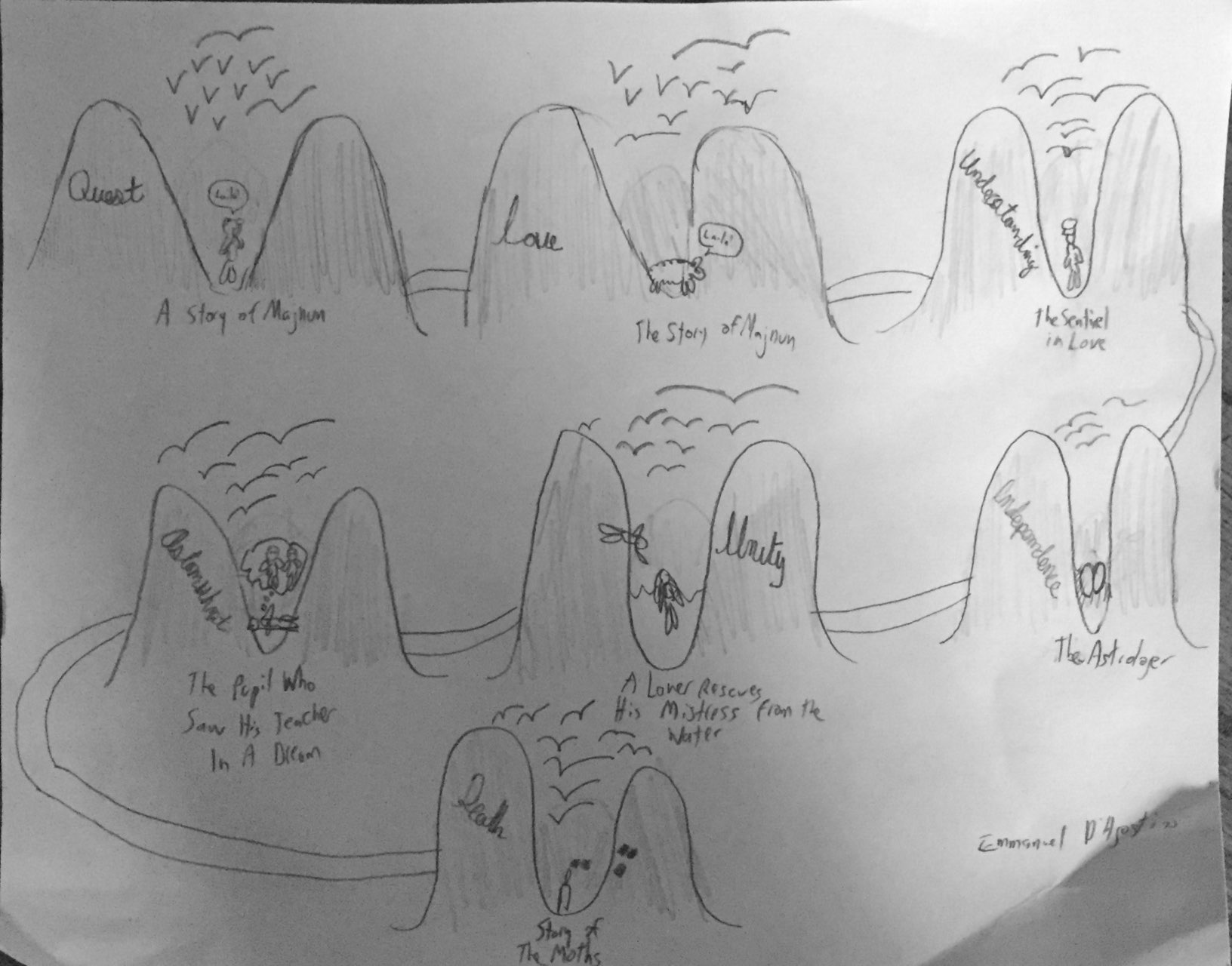

My fifth posting, like my first, counteracts anti-Islamic sentiment in a less overt way than my fourth or second. In it, I use pencil to draw an illustration of the seven valleys of the world of The Conference of the Birds, a long poem by Attar of Nishapur. I was inspired by the illustration of this world by Peter Sis, a well-regarded illustrator. While I lack his artistic talent, I like that my drawings included depictions of one of the stories from each valley, and I wish he had included that. There is nothing in The Conference of the Birds that directly addresses Islamophobia, as it was written long before September 11, 2001. It is merely a beautiful poem in an Islamic world, and thus speaks more directly to the original mission of AIU 54 of showing and analyzing the cultural and artistic diversity of the Muslim world. In doing so, however, it serves to counteract Islamophobia nonetheless. If more Americans thought of ideas and texts like Attar’s work, and fewer thought of terrorism and violence, when Islam is brought up in conversation, it would show progress against Islamophobia. The importance of reading, discussing, and sharing beautiful works like Attar’s cannot therefore be understated in the fight against Islamophobia.

My sixth and final piece is different from all the rest in that it is auditory, not visual. I set a beautiful ghazal, or Persian love poem, to music, and recited it. Because each couplet of a ghazal is its own poem, I set each one to a different piece of music or sound. Like Attar’s Conference of the Birds, I think this poem counteracts hatred of Islam indirectly. By showcasing the diversity and the beauty of Islamic art and culture, as AIU 54 itself aims to do, this poem fights against misconceptions and hatred of Islam in an indirect but nonetheless very important manner.

These six pieces can be grouped in various ways. The sixth is auditory, whereas the first five are visual. The ghazal, the Al-Ghazali piece, and the illustration of The Conference of the Birds all speak to the mission of AIU 54 by showcasing the diverse and beautiful nature of Islamic art and culture whereas the rap, the calligraphy, and the piece reflecting on Prophetic Light and Sulayman’s interpretation all offer a more overt response to hatred of Islamophobia and anti-Islamic sentiment. These pieces also all reflect Islam in a wide array of times and places, from modern rap music to ancient calligraphy, and can be grouped along either of these spectra.

Like Islam itself, these pieces therefore encompass a wide variety of ideas and beliefs, all grouped into my project the way many communities of interpretation come together to make up Islam. These communities of interpretation are groups that interpret Islamic thought and the Qu’ran in a variety of ways. Admittedly, some of these Muslim groups possess a violent, virulently anti-American ideology, but what many Islamophobes fail to realize is that the overwhelming, overwhelming majority of these groups are peaceful, tolerant, and pluralist. As I hope is clear, I tried to get at this idea in my project by showcasing the many, many ways across space and time in which the latter set of communities of interpretation express themselves through art.

Ideally, I hope that one day, discussions about Islam in American classrooms will encompass everything from ghazals to rap to theater to music, with fundamentalist terrorism and Islamophobia as a mere historical afterthought. Furthermore, I’d like to think that AIU 54, and, by extension, this project, help to bring us toward a world in which that is the case.

Thank you so much!

This drawing was inspired by Al-Ghazali’s ten guidelines for Qu’ran recitation and interpretation. I display his most ideal reading of the Qu’ran by showing a man following all of his guidelines. In addition to being art, this piece can also serve as a visual guide to Al-Ghazali’s work. The Arabic numbers for 1-10 are written throughout the piece, each corresponding to how the man displayed is following that guideline. To me, it makes sense to display these guidelines through visual art, since they are external guidelines. I think it is important that this drawing is ink, because using ink imitates the Qu’ran itself and connects it to it.

This drawing was inspired by Al-Ghazali’s ten guidelines for Qu’ran recitation and interpretation. I display his most ideal reading of the Qu’ran by showing a man following all of his guidelines. In addition to being art, this piece can also serve as a visual guide to Al-Ghazali’s work. The Arabic numbers for 1-10 are written throughout the piece, each corresponding to how the man displayed is following that guideline. To me, it makes sense to display these guidelines through visual art, since they are external guidelines. I think it is important that this drawing is ink, because using ink imitates the Qu’ran itself and connects it to it.