Kindle: not your parents’ eBook.

Comments: 7 - Date: November 29th, 2007 - Categories: Identity, Information Overload, Innovation, Learning, Participation Gap

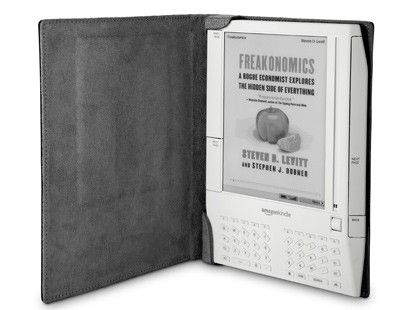

On November 19, Amazon.com announced its first foray into hardware: a portable eBook reader called the Kindle. Amazon hopes the Kindle will become the iPod of books – a portable personal library you can take anywhere.

That same day, the National Endowment for the Arts announced the results of a new study: young Americans are reading less.

So it makes sense that despite obvious similarities, the Kindle and the iPod target very different markets. Whereas Apple turned the iPod into an icon of digital native culture, Amazon is aiming the Kindle squarely at digital immigrants.

Look at the features Amazon is touting. A display that mimics the look of ink on paper. A built in wireless book store so you never have to touch a computer. The ability to change text size. In short, it’s designed for people who hate using computers and have bad eyesight.

Meanwhile, with a screen saver featuring the likes of Jane Austen and the Gutenberg printing press, along with what the popular technology blog Engadget calls “a big ol’ dose of the ugly,” the Kindle is almost aggressively unhip. As one analyst told the Wall Street Journal, “No one is going to buy Kindle for its sex appeal.”

Moreover, digital natives tend to be more comfortable reading from traditional LCD screens than their parents are. Indeed, some of us, myself included, actually prefer reading from a screen. I’d much rather read a book on, say, an iPhone, than have to carry a separate device.

But as the NEA study (3.3 MB PDF) makes clear, most readers aren’t digital natives. If older consumers take to the Kindle in droves, perhaps they could become the digital natives of literature, defining the new paradigm for how we read digital books.

In a sense then, whether knowingly or not, Amazon is performing a large scale social experiment. We can’t wait to see the results.

-Jesse Baer