This week, we are delighted to publish a guest post from Gaby David, a PhD candidate from the Lhivic (Laboratory for Contemporary Visual History) at the École des hautes études en sciences sociales in Paris. — Diana Kimball, DN Intern

Barack Obama’s presidential victory is captivating. Not only because of his personal charm, but also because of the force of hope he inspires. Being the first black president will definitely place him and his family in a special and touching place in history.

Let’s take a look at the two photographs. The first photo is from the Nov 1960 elections, when JFK was elected president. In the second one we see the democratic presidential nominee, Barack Obama and his family, on election night in Chicago, on November 4, 2008 (David Katz/Obama for America). Between the photos there are 48 years, the distance between president #35 and president #44. Differences are evident: black and white versus color film, family presence, the absence of children from one and the centrality of children to the other; the light of day versus the light of lamps.

However, in both photographs we imagine the out-of-frame object: the television! Moving images and screens have always held a hypnotic fascination…but, one of the biggest differences is that now we can see the television, and therefore know what the photographed people, in this case Obama, his family and close circle were watching at the moment the photographs were taken.

(Worth noting: in the second photograph, both Obama and the person standing are holding their cellphones.)

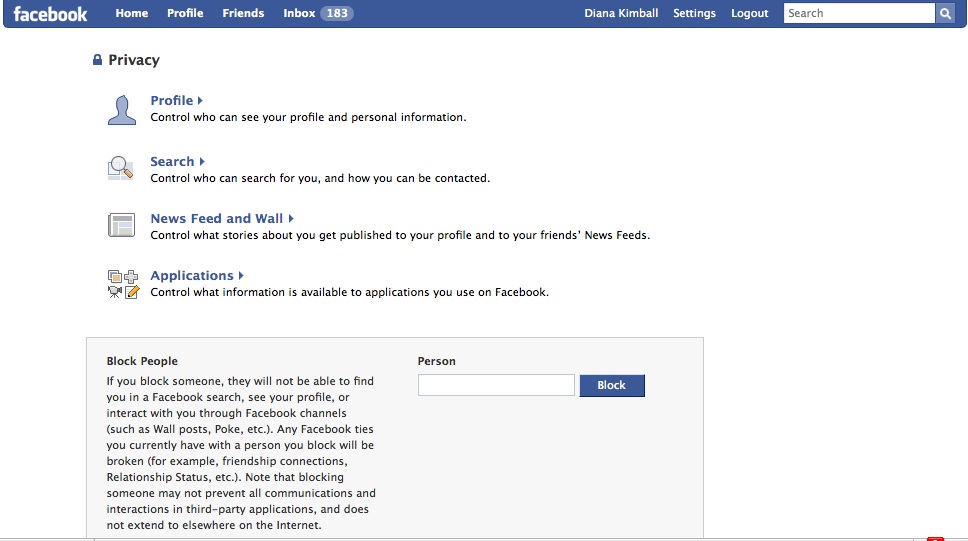

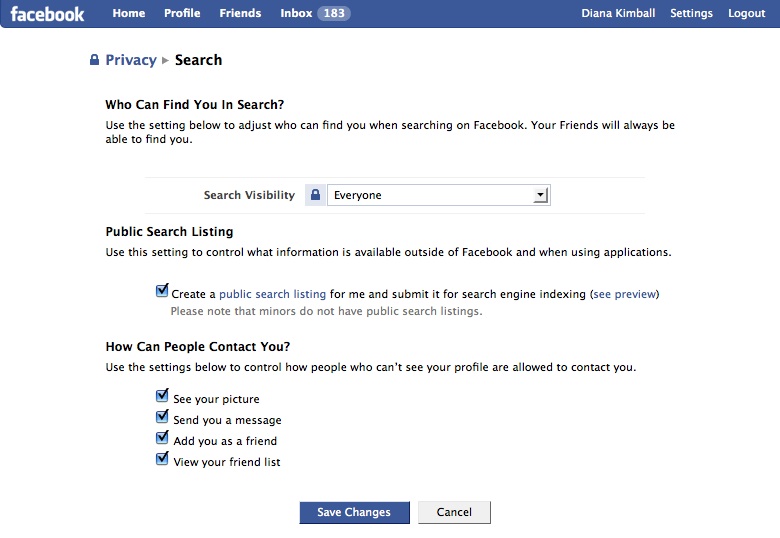

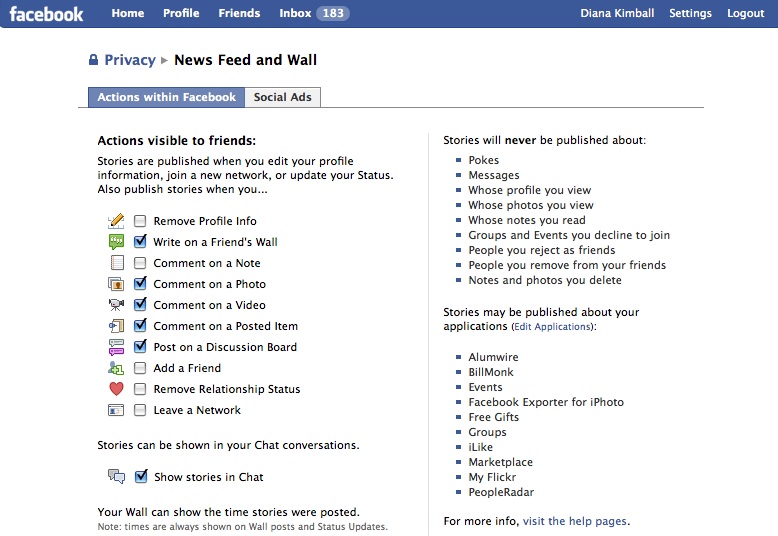

Each campaign has its particularities: JFK’s in 1960, Barack Obama’s in 2008. But out of all those particularities, one stands apart: the role the Internet played in this latest election. Barack Obama not only had and still has his website, both in English and Spanish, and his own YouTube channel, but also his own Facebook group and Flickr photo stream, where we can even discover with which camera these pictures were shot. The Obama presence was also on Myspace, Digg, Twitter, Eventful, LinkedIn, BlackPlanet, Faithbase, Eons, Glee, MiGente, MyBatanga, and AsianAve. To take just one example, by 11/24/08 the “Yes We Can” YouTube video had already been viewed 2,106,176 times. These various social networking and media sites served as proof of authenticity and transparency for anyone willing to connect with his campaign.

Of course, the established media channels (CNN, Fox, newspapers, etc.) did their own pertinent press coverage. But most of all, it was personal blogs and sites which contributed to this enormous flow of daily information that kept us glued to an interactive net.

Analyzing the Election Through Camphone-Video Broadcasts

Since my research at the Lhivic Lab at the École des hautes études en sciences sociales—the only Visual Studies department in Paris, and one of the best in Europe—focuses on the place of camphones in daily lives, I wanted to investigate the role that camphones played in individual voting experiences and how somebody like me, physically far from the States could follow the Election Day through the web and through “normal” people. It’s worth then looking at a few examples.

On Qik, some of the uploaded videos posted live, so that I—along with any other interested party—could watch big things happen live, and on the “small scale” intimated by the camphone.

Being able to share these anonymous people’s moments, and their feelings towards such an important day, has been both emotional and strange.

http://qik.com/video/521922

Two friends are driving in the rainy Election Day. The driver, Rhett, tells his mate and the blogosphere about his voting experience. Why had he decided to go for early voting? What happened with his son? He tells us about how he was explaining to his boy about the process of democracy and privacy. Then both, Rhett and his friend, discuss how they are going to watch or follow “the event.” His friend says he is going to watch the election results on Twitter: ‘cause “opinions are in real time!” Rhett replies: “well, not watching it, you are just seeing the feed come in…”

(Actually, this is intriguing: do we read or do we watch a text that is on a screen?)

They continue talking about how Rhett’s family used to watch the results together; a family tradition, the same as Obama’s photo stream shows. Rhett will also tune in and stay up late with his family and see the interactive map turn red or blue.

From this short video we get to know a lot of information:

– where and when the video was shot,

– what the weather was like,

– how both friends feel about Election Day,

– that one of them is married and has a four and a half year old son, etc.

At last, they are so much into the sharing and the mediation of their experience that they forget to take the highway exit they were supposed to.

Another special topic of this election was the lines. People were really surprised about the quantity of people that showed up to vote. So, many of the videos show and inform us about the waiting time or the “queue stats.” For example, Robert Stevens shows that “now” there is no one.

http://qik.com/video/523265

Roddykat also shares with us this waiting “dead moment” and turns it into an imaging production moment. There is no real intention, he does not master the outcome, but that does not really matter. It is uploaded live, and by 11/24/2008 it had 37 views. It is more than probable that Roddykat himself did not see his own camphone video before uploading it; he was just queuing and sent it to his Qik account.

http://qik.com/video/521961

We see images switch from horizontal to vertical: a particular and specific characteristic seen in many camphone videos. It is as though the linearity of both the shooting and the viewing are no longer that important.

From Roddykat’s Qik page there is a link to his website. From his site a link to his Twitter.

On November 4th at exactly 5:49 A.M. Roddykat’s twitter is a link towards his twitterpic page. Once again, as though we were detectives, we get to know he is almost there in the voting booth.

With something like the feeling of a suspense film, this very special moment of Roddykat’s life is being shared and broadcasted live….

First it’s “the wait for the polls to open”

then it’s “Inside now”

then “View from inside out”

and, at last, “Almost there”:

In the last photograph we see a close up of the back of the head of the person who was standing before him. The queue line disappears into a contrasted white.

At the end, we realize: whether through Twitter or Qik, every method that Roddykat used to publish his in-the-moment experiences was mediated by a camphone.

Some Final Conclusions

As with almost all Qik videos, here the chosen videos are only shot; there is no post-editing. Today, camphones are used not only as voice transmitters but also as tools for sharing images. As O. Daisuke and M. Ito said years ago, “camera phones are changing the definition of what is picture-worthy,” and as Kindberg et al. also say: “A camera phone’s value might not lie in sending images but in using the captured images for other activities.”

http://qik.com/video/526162

References

• Borsch, Steve, “Lessons From Our First “Social Media” President”, Minnesota Innovation in Internet & Web Technology, November 5th, 2008, http://minnov8.com/2008/11/05/social-media-pres/

• Daisuke, Okabe and Ito, Mizuko, “Camera phones changing the definition of picture-worthy”, Japan Media Review, 29th August, 2003, http://www.ojr.org/japan/wireless/1062208524.php

• Kindberg et al, “The Ubiquitous Camera: An In-Depth Study of Camera Phone Use”, Pervasive Computing, 2nd April 2005, http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1056962

• http://www.flickr.com/photos/barackobamadotcom/

• Mclaughlin, Rhett, “untitled”, November 4th, 2008, camphone video, 6:05 minutes, http://qik.com/video/521922

• Stevens, Robert, “#votreport #10009”, November 4th, 2008, camphone video, 17 seconds, http://qik.com/video/523265

• Rodney L, “Election day 09’”, November 4th, 2008, camphone video, 35 seconds, http://qik.com/video/521961

• theuptake, “Exited Obama Supporters in Denver”, November 4th, 2008, camphone video, 31 seconds, http://qik.com/video/526162

*All links were accessed on November 24th, 2008.

* Special thanks to Diana Kimball for proof reading.

…………………

Gaby David, born in Uruguay, is a PhD candidate from the Lhivic (Laboratory for Contemporary Visual History) at the École des hautes études en sciences sociales (EHESS). At the Lhivic she co-coordinates both the Methodological workshop and the Lhivic’s students’ collective blog.

G. David holds a masters degree in Fine Arts from the University of Paris 8, Saint Denis.

A versatile scholar, her professional experience is both in the fields of arts and languages teaching. With a curious soul, she has already lived in Uruguay, in the United States and in Israel. In Nov. 2002 she moved to Paris and has been living there since.

Her actual field of research is the study of camphone videos—understanding how these images can be at the same time very intimate and publicly shared. Through her research, she is trying to decipher the intriguing part of the camphone: its familiarity. How the role of contemporary camphone visual auto-mediation of our daily lives is increasing, especially on the web. Because, contradictorily, the camphone videos that mirror us show us that familiarity never ceases to amaze us.

Email: championnet4@yahoo.fr

Gaby David on Facebook