This post provides an overview of stemming and presents a real world case in which it led to undesirable behavior.

Stemming is a common technique in natural language processing and information retrieval. The idea is that different forms of a word refer to the same concept. So, when a user searches for a word, the system should return documents containing all forms of the word. For example, if a user searches for ‘running’, they probably want to see documents containing the words ‘run’, ‘runs’, and ‘runner’ in addition to ‘running’. Stemming enables this by converting each form of a word to a common base or ‘stem’. For example, ‘run’, ‘runs’, ‘runner’, and ‘running’ would all be converted to ‘run’. Usually this is done using algorithmic techniques to remove word suffixes rather than with dictionary look ups. Algorithms perform almost as well as dictionary lookups and are simpler to implement. Also they can handle new words e.g. ‘iPhone’.

Stemming is intuitively appealing. But is it actually helpful in practice? The textbook example of stemming causing problems is that ‘business’ and ‘busy’ map to the same stem but represent different concepts. However, this example feels artificial.

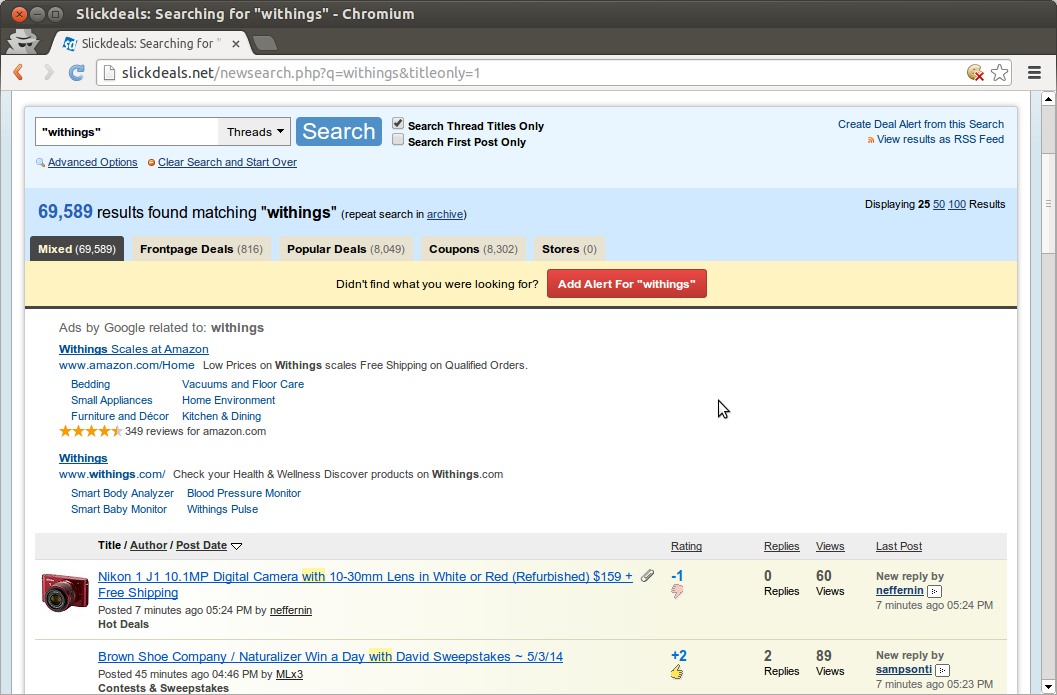

Here’s a real example. I recently searched for “Withings” on Slickdeals.net — the one of top sites for finding deals and coupons. As you can see in the screenshots below, Slickdeals returned results containing the word ‘with’:

What’s happening here? It’s likely that Slickdeals has a stemmer that converts ‘withings’ to ‘with’ using the programmatic rule of removing the ‘ings’ suffix. (Usually this would be the correct behavior. Consider “clip”, “clipping”, and “clippings”). Thus instead of returning results that contain ‘withings’, it returns results that contain ‘with’.

Often, sites can mitigate these type of problems by changing the order in which results are presented so that documents matching the exact search term appear before those only matching the stem. For example, most users only look at the first few pages of Google results. It doesn’t matter if there are false positives if they rank too low in the search results for users to actually see. (Ranking search results is a complex science. Google became successful largely because it was better at determining which matches were most relevant rather than because it delivered more total matches.) However, Slickdeals needs to sort results by time to meet the needs of its users because deals expire quickly. Knowing that there was a brief sale on an item 3 years ago isn’t particularly useful if you want to buy one now.

Stemming can be a useful tool but it’s important to understand its drawbacks. While there are certainly use cases in which the benefits outweigh the drawbacks, stemming should not be blindly adopted.