We’re not watching any less TV. In fact, we’re watching more of it, on more different kinds of screens. Does this mean that TV absorbs the Net, or vice versa? Or neither? That’s what I’m exploring here. By “explore” I mean I’m not close to finished, and never will be. I’m just vetting some ideas and perspectives, and looking for help improving them.

TV 1.0: The Antenna Age

In the beginning, 100% of TV went out over the air, radiated by contraptions atop towers or buildings, and picked up by rabbit ears on the backs of TV sets or by bird roosts on roofs. “Cable” was the wire that ran from the roof to the TV set. It helps to understand how this now-ancient system worked, because its main conceptual frame — the channel, or a collection of them — is still with us, even though the technologies used are almost entirely different. So here goes.

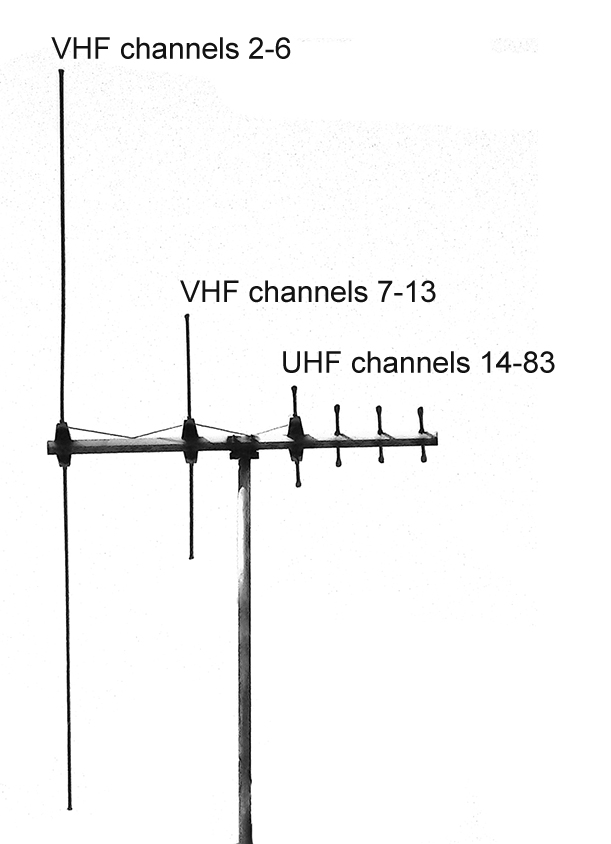

On the left is a typical urban rooftop TV antenna. The different lengths of the antenna elements correspond roughly to the wavelengths of the signals. For reception, this mattered a lot.

In New York City, for example, TV signals all came from the Empire State Building — and still do, at least until they move to the sleek new spire atop One World Trade Center, aka the Freedom Tower. (Many stations were on the North Tower of the old World Trade center, and perished with the rest of the building on 9/11/2001. After that, they moved back to their original homes on the Empire State Building.)

“Old” in the right photo refers to analog, and “new” to digital. (An aside: FM is still analog. Old and New here are just different generations of transmitting antennas. The old FM master antenna is two rings of sixteen T-shaped things protruding above and below the observation deck on the 102nd floor. It’s still in use as an auxiliary antenna. Here’s a similar photo from several decades back, showing the contraptual arrangement at the height of the Antenna Age.)

Channels 2-6 were created by the FCC in the 1940s (along with FM radio, which is in a band just above TV channel 6). Those weren’t enough channels, so 7-13 came along next, on higher frequencies — and therefore shorter wavelengths. Since the shorter waves don’t bend as well around buildings and terrain, stations on channels 7-13 needed higher power. So, while the maximum power for channels 2-6 was 100,000 watts, the “equivalent” on channels 7-13 was 316,000 watts. All those channels were in VHF bands, for Very High Frequency. Channels 14-83 — the UHF, or Ultra High Frequency band, was added in the 1950s, to make room for more stations in more places. Here the waves were much shorter, and the maximum transmitted power for “equivalent” coverage to VHF was 5,000,000 watts. (All were ERP, or effective radiated power, toward the horizon.)

This was, and remains, a brute-force approach to what we now call “delivering content.” Equally brute approaches were required for reception as well. To watch TV, homes in outer suburban or rural areas needed rooftop antennas that looked like giant centipedes.

What they got — analog TV — didn’t have the resolution of today’s digital TV, but it was far more forgiving of bad reception conditions. You might get “ghosting” from reflected signals, or “snow” from a weak signal, but people put up with those problems just so they could see what was on.

More importantly, they got hooked.

TV 2.0: the Cable Age.

It began with CATV, or Community Antenna Television. For TV junkies who couldn’t get a good signal, CATV was a godsend. In the earliest ’70s I lived in McAfee, New Jersey, deep in a valley, where a rabbit-ears antenna got nothing, and even the biggest rooftop antenna couldn’t do much better. (We got a snowy signal on Channel 2 and nothing else.) So when CATV came through, giving us twelve clear channels of TV from New York and Philadelphia, we were happy to pay for it. A bit later, when we moved down Highway 94 to a high spot south of Newton, my rooftop antenna got all those channels and more, so there was no need for CATV there. Then, after ’74, when we moved to North Carolina, we did without cable for a few years, because our rooftop antennas, which we could spin about with a rotator, could get everything from Roanoke, Virginia to Florence, South Carolina.

But then, in the early ’80s, we picked up on cable because it had Atlanta “superstation” WTCG (later WTBS and then just TBS) and HBO, which was great for watching old movies. WTCG, then still called Channel 17, also featured the great Bill Tush. (Sample here.) The transformation of WTCG into a satellite-distributed “superstation” meant that a TV station no longer needed to be local, or regional. For “super” stations on cable, “coverage” and “range” became bugs, not features.

Cable could also present viewers with more channels than they could ever get over the air. Technical improvements gradually raised the number of possible channels from dozens to hundreds. Satellite systems, which replicated cable in look and feel, could carry even more channels.

Today cable is post-peak. See here:

That’s because, in the ’90s, cable also turned out to be ideal for connecting homes to the Internet. We were still addicted to what cable gave us as “TV,” but we also had the option to watch a boundless variety of other stuff — and to produce our own. Today people are no less hooked on video than they were in 1955, but a declining percentage of their glowing-rectangle viewing is on cable-fed TV screens. The main thing still tying people to cable is the exclusive availability of high-quality and in-demand shows (including, especially, live sports) over cable and satellite alone.

This is why apps for CNN, ESPN, HBO and other cable channels require proof of a cable or satellite TV subscription. If cable content was á la carte, the industry would collapse. The industry knows this, of course, which makes it defensive.

That’s why Aereo freaks them out. Aereo is the new company that Fox and other broadcasters are now suing for giving people who can’t receive TV signals a way to do that over the Net. The potential served population is large, since the transition of U.S. television from analog to digital transmission (DTV) was, and remains, a great big fail.

Where the FCC estimated a 2% loss of analog viewers after the transition in June 2009, in fact 100% of the system changed, and post-transition digital coverage was not only a fraction of pre-transition analog coverage, but required an entirely new way to receive signals, as well as to view them. Here in New York, for example, I’m writing this in an apartment that could receive analog TV over rabbit ears in the old analog days. It looked bad, but at least it was there. With DTV there is nothing. For apartment dwellers without line-of-sight to the Empire State Building, the FCC’s reception maps are a fiction. Same goes for anybody out in the suburbs or in rural areas. If there isn’t a clear-enough path between the station’s transmitter and your TV’s antenna, you’re getting squat.

TV stations actually don’t give much of a damn about over-the-air any more, because 90+% of viewers are watching cable. But TV stations still make money from cable systems, thanks to re-transmission fees and “must carry” rules. These rules require cable systems to carry all the signals receivable in the area they serve. And the coverage areas are mostly defined by the old analog signal footprints, rather than the new smaller digital footprints, which are also much larger on the FCC’s maps than in the realities where people actually live.

Aereo gets around all that by giving each customer an antenna of their own, somewhere out where the signals can be received, and delivering each received station’s video to customers over the Net. In other words, it avoids being defined as cable, or even CATV. It’s just giving you, the customer, your own little antenna.

This is a clever technical and legal hack, and strong enough for Aereo towin in court. After that victory, Fox threatened to take its stations off the air entirely, becoming cable- and satellite-only. This exposed the low regard that broadcasters hold for their over-the-air signals, and for broadcasting’s legacy “public service” purpose.

The rest of the Aereo story is inside baseball, and far from over. (If you want a good rundown of the story so far, dig Aereo: Reinventing the cable TV model, by Tristan Louis.)

Complicating this even more is the matter of “white spaces.” Those are parts of the TV bands where there are no broadcast signals, or where broadcast signals are going away. These spaces are valuable because there are countless other purposes to which signals in those spaces could be put, including wireless Internet connections. Naturally, TV station owners want to hold on to those spaces, whether they broadcast in them or not. And, just as naturally, the U.S. government would like to auction the spaces off. (To see where the spaces are, check out Google’s “spectrum browser“. And note how few of them there are in urban areas, where there are the most remaining TV signals.)

Still, TV 2.0 through 2.9 is all about cable, and what cable can do. What’s happening with over-the-air is mostly about what the wonks call policy. From Aereo to white spaces, it’s all a lot of jockeying for position — and making hay where the regulatory sun shines.

Meanwhile, broadcasters and cable operators still hate the Net, even though cable operators are in the business of providing access to it. Both also remain in denial about the Net’s benefits beyond serving as Cable 2.x. They call distribution of content over the Net (e.g. through Hulu and Netflix) “over the top” or OTT, even though it’s beyond obvious that OTT is the new bottom.

FCC regulations regarding TV today are in desperate need of normalizing to the plain fact that the Net is the new bottom — and incumbent broadcasters aren’t the only ones operating there. But then, the feds don’t understand the Net either. The FCC’s world is radio, TV and telephony. To them, the Net is just a “service” provided by phone and cable companies.

TV 3.0: The IPTV age

IPTV is TV over the Internet Protocol — in other words, through the open Internet, rather than through cable’s own line-up of channels. One example is Netflix. By streaming movies over the Net, Netflix put a big dent in cable viewing. Adding insult to that injury, the vast majority of Netflix streamed movies are delivered over cable connections, and cable doesn’t get a piece of the action, because delivery is over OTT, via IPTV. And now, by producing its own high-quality shows, such as House of Cards, Netflix is competing with cable on the program front as well. To make the viewing experience as smooth as possible for its customers, Netflix also has its own equivalent of a TV transmitter. It’s called OpenConnect, and it’s one among a number of competing CDNs, or Content Delivery Networks. Basically they put up big server farms as close as possible to large volumes of demand, such as in cities.

So think of Netflix as a premium cable channel without the cable, or the channel, optimized for delivery over the Internet. It carries forward some of TV’s norms (such as showing old movies and new TV shows for a monthly subscription charge) while breaking new ground where cable and its sources either can’t or won’t go.

Bigger than Netflix, at least in terms of its catalog and global popularity, is Google’s YouTube. If you want your video to be seen by the world, YouTube is where you put it today, if you want maximum leverage. YouTube isn’t a monopoly for Google (the list of competitors is long), but it’s close. (According to Alexa, YouTube is accessed by a third of all Internet users worldwide. Its closest competitor (in the U.S., at least), is Vimeo, with a global reach of under 1%.) So, while Netflix looks a lot like cable, YouTube looks like the Web. It’s Net-native.

Bassem Youssef, “the Jon Stewart of Egypt,” got his start on YouTube, and then expanded into regular TV. He’s still on YouTube, even though his show on TV got canceled when he was hauled off to jail for offending the regime. Here he tells NBC’s Today show, “there’s always YouTube.” [Later… Dig this bonus link.]

But is there? YouTube is a grace of Google, not the Web. And Google is a big advertising business that has lately been putting more and more ads, TV-like, in front of videos. Nothing wrong with that, it’s a proven system. The question, as we move from TV 3.0 to 3.9, is whether the Net and the Web will survive the inclusion of TV’s legacy methods and values in its midst. In The TV in the Snake of Time, written in July 2010, I examined that question at some length:

Television is deeply embedded in pretty much all developed cultures by now. We — and I mean this in the worldwide sense — are not going to cease being couch potatoes. Nor will our suppliers cease couch potato farming, even as TV moves from airwaves to cable, satellite, and finally the Internet.

In the process we should expect the spirit (if not also the letter) of the Net’s protocols to be violated.

Follow the money. It’s not for nothing that Comcast wishes to be in the content business. In the old cable model there’s a cap on what Comcast can charge, and make, distributing content from others. That cap is its top cable subscription deals. Worse, they’re all delivered over old-fashioned set top boxes, all of which are — as Steve Jobs correctly puts it — lame. If you’re Comcast, here’s what ya do:

- Liberate the TV content distro system from the set top sphincter.

- Modify or re-build the plumbing to deliver content to Net-native (if not entirely -friendly) devices such as home flat screens, smartphones and iPads.

- Make it easy for users to pay for any or all of it on an à la carte (or at least an easy-to-pay) basis, and/or add a pile of new subscription deals.

Now you’ve got a much bigger marketplace, enlarged by many more devices and much less friction on the payment side. (Put all “content” and subscriptions on the shelves of “stores” like iTunes’ and there ya go.) Oh, and the Internet? … that World of Ends that techno-utopians (such as yours truly) liked to blab about? Oh, it’s there. You can download whatever you want on it, at higher speeds every day, overall. But it won’t be symmetrical. It will be biased for consumption. Our job as customers will be to consume — to persist, in the perfect words of Jerry Michalski, as “gullets with wallets and eyeballs.”

So, for current and future build-out, the Internet we techno-utopians know and love goes off the cliff while better rails get built for the next generations of TV — on the very same “system.” (For the bigger picture, Jonathan Zittrain’s latest is required reading.)

In other words, it will get worse before it gets better. A lot worse, in fact.

But it will get better, and I’m not saying that just because I’m still a utopian. I’m saying that because the new world really is the Net, and there’s a limit to how much of it you can pave with one-way streets. And how long the couch potato farming business will last.

More and more of us are bound to produce as well as consume, and we’ll need two things that a biased-for-TV Net can’t provide. One is speed in both directions: out as well as in. (“Upstream” calls Sisyphus to mind, so let’s drop that one.) The other is what Bob Frankston calls “ambient connectivity.” That is, connectivity we just assume.

When you go to a hotel, you don’t have to pay extra to get water from the “hydro service provider,” or electricity from the “power service provider.” It’s just there. It has a cost, but it’s just overhead.

That’s the end state. We’re still headed there. But in the meantime the Net’s going through a stage that will be The Last Days of TV. The optimistic view here is that they’ll also be the First Days of the Net.

Think of the original Net as the New World, circa 1491. Then think of TV as the Spanish invasion. Conquistators! Then read this essay by Richard Rodriguez. My point is similar. TV won’t eat the Net. It can’t. It’s not big enough. Instead, the Net will swallow TV. Ten iPad generations from now, TV as we know it will be diffused into countless genres and sub-genres, with millions of non-Hollywood production centers. And the Net will be bigger than ever.

In the meantime, however, don’t hold your breath.

That meantime has now lasted nearly three years — or much longer if you go back to 1998, when I wrote a chapter of a book by Microsoft, right after they bought WebTV. An excerpt:

The Web is about dialog. The fact that it supports entertainment, and does a great job of it, does nothing to change that fact. What the Web brings to the entertainment business (and every business), for the first time, is dialog like nobody has ever seen before. Now everybody can get into the entertainment conversation. Or the conversations that comprise any other market you can name. Embracing that is the safest bet in the world. Betting on the old illusion machine, however popular it may be at the moment, is risky to say the least…

TV is just chewing gum for the eyes. — Fred Allen

This may look like a long shot, but I’m going to bet that the first fifty years of TV will be the only fifty years. We’ll look back on it the way we now look back on radio’s golden age. It was something communal and friendly that brought the family together. It was a way we could be silent together. Something of complete unimportance we could all talk about.

And, to be fair, TV has always had a very high quantity of Good Stuff. But it also had a much higher quantity of drugs. Fred Allen was being kind when he called it “chewing gum for the eyes.” It was much worse. It made us stupid. It started us on real drugs like cannabis and cocaine. It taught us that guns solve problems and that violence is ordinary. It disconnected us from our families and communities and plugged us into a system that treated us as a product to be fattened and led around blind, like cattle.

Convergence between the Web and TV is inevitable. But it will happen on the terms of the metaphors that make sense of it, such as publishing and retailing. There is plenty of room in these metaphors — especially retailing — for ordering and shipping entertainment freight. The Web is a perfect way to enable the direct-demand market for video goods that the television industry was never equipped to provide, because it could never embrace the concept. They were in the eyeballs-for-advertisers business. Their job was to give away entertainment, not to charge for it.

So what will we get? Gum on the computer screen, or choice on the tube?

It’ll be no contest, especially when the form starts funding itself.

Bet on Web/TV, not TV/Web.

I was recruited to write that chapter because I was the only guy Microsoft could find who thought the Web would eat TV rather than vice versa. And it does look like that’s finally happening, but only if you think Google is the Web. Or if you think Web sites are the new channels. In tech-speak, channels are silos.

When I wrote those pieces, I did not foresee the degree to which our use of the Net would be contained in silos that Bruce Schneier compares to feudal-age castles. Too much of the Web we know today is inside the walls governed by Lord Zuck, King Tim, Duke Jeff and the emperors Larry and Sergey. In some ways those rulers are kind and generous, but we are not free so long as we are native to their dominions rather than the boundless Networked world on which they sit.

The downside of depending on giants is that you can, and will, get screwed. Exhibit A (among too many for one alphabet) is Si Dawson’s goodbye post on Twitcleaner, a service to which he devoted his life, and countless people loved, that “was an engineering marvel built, as it were, atop a fail-whaling ship.” When Twitter “upgraded” its API, it sank Twitcleaner and many other services built on Twitter. Writes Si, “Through all this I’ve learned so, so much.Perhaps the key thing? Never playfootball when someone else owns the field. So obvious in hindsight.”

Now I’m having the same misgivings about Dropbox, which works as what Anil Dash calls a POPS: Privately Owned Public Space. It’s a great service, but it’s also a private one. And therefore risky like Twitter is risky.

What has happened with all those companies was a morphing of mission from a way to the way:

- Google was a way to search, and became the way to search

- Facebook was a way to be social on the Web, and became the way to be social on the Web

- Twitter was a way to microblog, and became the way to microblog

I could go on, but you get the idea.

What makes the Net and the Web open and free are not its physical systems, or any legal system. What makes them free are their protocols, which are nothing more than agreements: the machine equivalents of handshakes. Protocols do not by their nature presume a centralized system, like TV — or like giant Web sites and services. Protocols are also also not corruptible, because they are each NEA: Nobody owns it, Everybody can use it and Anybody can improve it.

Back in 2003, David Weinberger and I wrote about protocols and NEA in a site called World of Ends: What the Internet Is and How to Stop Mistaking It For Something Else. In it we said the Net was defined by its protocols, not by the companies providing the wiring and the airwaves over which we access the Net.

Yet, a decade later, we are still mistaking the Net for TV. Why? One reason is that there is so much more TV on the Net than ever before. Another is that we get billed for the Net by cable and phone companies. For cable and phone companies providing home service, it’s “broadband” or “high speed Internet.” For mobile phone companies, it’s a “data plan.” By whatever name, it’s one great big channel: a silo open at both ends, through which “content” gets piped to “consumers.” To its distributors — the ones we pay for access — it’s just another kind of cable TV.

The biggest player in cable is not Comcast or Time Warner. It’s ESPN. That’s because the most popular kind of live TV is sports, and ESPN runs that show. Today, ESPN is moving aggressively to mobile. In other words, from cable to the Net. Says Bloomberg Businessweek,

ESPN has been unique among traditional media businesses in that it has flourished on the Web and in the mobile space, where the number of users per minute, which is ESPN’s internal metric, reached 102,000 in June, an increase of 48 percent so far this year. Mobile is now ESPN’s fastest-growing platform.

Now, in ESPN Eyes Subsidizing Wireless-Data Plans, the Wall Street Journal reports, “Under one potential scenario, the company would pay a carrier to guarantee that people viewing ESPN mobile content wouldn’t have that usage counted toward their monthly data caps.” If this happens, it would clearly violate the principle of network neutrality: that the network itself should not favor one kind of data, or data producer, over another.Such a deal would instantly turn every competing data producer into a net neutrality activist, so it’s not likely to happen.

Meanwhile John McCain, no friend of net neutrality, has introduced the TV Consumer Freedom Act, which is even less friendly to cable. As Business Insider puts it, McCain wants to blow the sucker up. Says McCain,

This legislation has three principal objectives: (1) encourage the wholesale and retail ‘unbundling’ of programming by distributors and programmers; (2) establish consequences if broadcasters choose to ‘downgrade’ their over-the-air service; and (3) eliminate the sports blackout rule for events held in publicly-financed stadiums.

For over 15 years I have supported giving consumers the ability to buy cable channels individually, also known as ‘a la carte’ – to provide consumers more control over viewing options in their home and, as a result, their monthly cable bill.

The video industry, principally cable companies and satellite companies and the programmers that sell channels, like NBC and Disney-ABC, continue to give consumers two options when buying TV programming: First, to purchase a package of channels whether you watch them all or not; or, second, not purchase any cable programming at all.

This is unfair and wrong – especially when you consider how the regulatory deck is stacked in favor of industry and against the American consumer.

Unbundle TV, make it á la carte, and you have nothing more than subscription video on the Net. And that is what TV will become. If McCain’s bill passes, we will still pay Time Warner and Comcast for connections to the Net; and they will continue to present a portfolio of á la carte and bundled subscription options. Many video sources will continue to be called “networks” and “channels.” But it won’t be TV 4.0 because TV 3.0 — TV over IP — will be the end of TV’s line.

Shows will live on. So will producers and artists and distributors. The old TV business to be as creative as ever, and will produce more good stuff than ever. Couch potatoes will live too, but there will be many more farmers, and the fertilizer will abound in variety.

What we’ll have won’t be TV because TV is channels, and channels are scarce. The Net has no channels, and isn’t about scarcity. It just has an endless number of ends, and no limit on the variety of sources pumping out “content” from those ends. Those sources include you, me, and everybody else who wants to produce and share video, whether for free or for pay.

The Net is an environment built for abundance. You can put all the scarcities you want on it, because an abundance-supporting environment allows that. An abundance system such as the Net gives business many more ways to bet than a scarcity system such as TV has been from the antenna age on through cable. As Jerry Michalski says (and tweets), “#abundance is pretty scary, isn’t it? Yet it’s the way forward.”

Abundance also frees all of us personally. How we organize what we watch should be up to us, not up to cable systems compiling their own guides that look like spreadsheets, with rows of channels and columns of times. We can, and should, do better than that. We should also do better than what YouTube gives us, based on what its machines think we might want.

The new box to think outside of is Google’s. So let’s re-start there. TV is what it’s always been: dumb and terminal.

Leave a Reply