In What the ad biz needs is writers, Michael Wolff bemoans the absence of good writers in advertising:

In What the ad biz needs is writers, Michael Wolff bemoans the absence of good writers in advertising:

…even creatives want to avoid writing — because they can’t…

While technological disruption is most often blamed for the existential predicament of the media business, the more precise problem is that advertising doesn’t work as well as it used to work. This presents a crisis not only for newspapers, magazines and television — but also, according to the stock market, for Facebook. We just don’t look at advertising, respond to it, or believe it, as much as we once did, wherever it appears.

Maybe this is the reason: There are no writers in advertising anymore. Johnny who can’t write has gone into advertising.

In fact, “copywriter” is a job that now hardly exists. The historical partnership between graphic designer and copywriter has, more and more, become a partnership between project manager and programmer, or videographer and editor, or media buyer and researcher.

If you are the person who actually has to write an ad — rather than conceptualize, or produce, or program, or pitch, or research — your career in advertising is not going very well.

He is right. That he’s one of the best writers in journalism adds weight to his judgement. So does this, which closes his piece:

My suggestion to USA TODAY editors was to let the opportunity of the page encourage an agency and client to brilliantly use it. A contest — always beloved in the ad business — was suddenly born.

USA TODAY is offering a million dollars in free advertising pages if you can fill them smartly — with cleverness, wit, style, economy of words. Again, free. Now, that will make your client happy.

Just spell out your big idea and tell your arresting story.

It may be that all we have to do to reinvent traditional media, save Facebook, even make digital media a decent business, as well as move more merchandise, is bring back the copywriter.

I’m for that — and I’m eager to see how the ad business responds to the contest.

But I also think the problem is bigger than writing itself, or technological disruption.

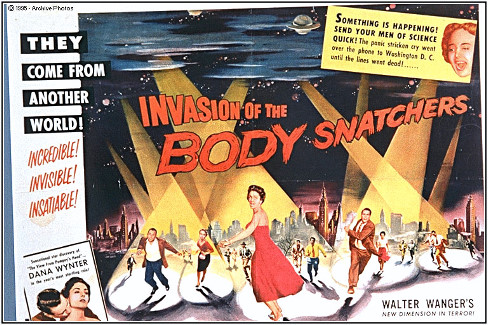

The problem is that direct marketing has body-snatched advertising.

In the old days direct marketing was distinct from adverting. In even older days, direct marketing was called direct mail. Or, in the vernacular of its recipients, junk mail. Some key differences, from back in the pre-snatched era of advertising’s history:

- While advertising was impersonal, direct marketing was personal. It called you by name. Or wanted to.

- While advertising was about raising general awareness of a company, product or service, direct marketing was about selling you stuff. Hence the term direct response, which is what most of direct marketing on the Net is looking for today.

- While advertising was creative-driven, direct marketing was data-driven.

- While advertising favored qualitative results, direct marketing favored quantitative results.

- While advertising respected personal privacy by default (it didn’t get personal), direct marketing never cared much about it — despite assurances to the contrary.

In the old analog world, advertising and direct marketing remained blessedly separate. No first-rank copywriter, art director or creative director wanted to tar his or her hands (or resumé) with direct marketing work. In fact, most of that work didn’t happen on Madison Avenue at all, but in specialty shops somewhere out in Florida or Indiana.

But once the analog and the digital world merged, direct marketing’s obsession with data gathering and analysis had nearly infinite room to grow. Like cancer, or worse.

It seemed innocent enough when it was just text ads off to the side of Google search results, or on the margins of blogs and other Web pubs. That stuff was called advertising because, well, it was. And that’s when the body-snatch began. Because that stuff was called advertising, so was everything that followed when direct marketing imperatives and methods moved to the fore.

In the online world, advertising messages are not much about increasing brand awareness, or other old-fashioned advertising purposes. (Though today’s ad folk love to throw the word “brand” around.) Instead the main purpose is getting direct responses: clicks and sales, aimed by personal data, gathered and analyzed every possible way. The idea is to make the advertising as personal as possible, as far as possible, regardless of how creepy it gets. It’s all fully rationalized. (Hey, you can opt out if you don’t like it.)

In the analog world of old-fashioned Madison Avenue advertising, there were physical limits to saturation. Not so online. Today advertising comprises 99.x% of all email traffic. (Most of it is spam, but it’s hard to tell the difference.) It has also turned ad-supported Web pages into syringes for injecting countless unseen files into users’ browsers. Those files then follow users everywhere to collect data for the new ad industry’s analytic mills, so the body-snatched business can then deliver “a better advertising experience,” as if anybody actually wants it.

And now the snatched ad business want to dominate our mobile lives as well. For a taste of how this looks on the ad-mill side, check out MediaPost‘s MobileMarketing Daily. Lots of rah-rah for what most phone users can only dread. Examples:

- Google Enhanced Campaigns Push Search Budgets To Mobile

- Twitter Files S-1, Mobile Drives Two-Thirds Of Ad Dollars

- M&A Activity Hits $67.5 Billion In 2013 (The focus is on M&A around mobile marketing.)

- Google’s Flutter Acquisition Means Another Step Closer To Gesture-Based Search Marketing

They do, however, report on some push-back:

Yet there is one thing both traditional advertising folk and direct marketers have in common, and that’s blinders toward reality. Terry Heaton puts it well:

Operating within the soul of every marketer is the ridiculous assumption that people want or need to be bombarded by advertising, and that any invasion of their time or experience to “pass along” an attempt to influence is justified. If this were true, there would be no looming fight over DVRs, which allow viewers to skip ads. You have no inherent right to my eyeballs, and it is precisely this axiom that makes today’s instruments and gadgets so powerfully disruptive to the culture.

How so? We’re weary of running a relentless gauntlet of jumping, screaming, frantic warnings, hands grabbing, voices shouting, noise-making, disjointed movements, and the almost demonic reaching for our wallets coming from advertising. This is Madison Avenue’s idea of perfection, and the only way you can get there is to completely ignore the effect of advertising on the very people you’re trying to influence. The Web is, at core, a pull mechanism, not one that pushes. It’s why all those big projections of advertising “potential” have turned into a commodified “pennies for dollars” reality.

In reality, advertising has become ineffective because it is no longer advertising, at least in the digital world. It is direct marketing, calling itself advertising.

To live again as a stand-alone discipline, advertising needs to exorcize the devil that direct marketing has made of advertising online. Simple as that.

For more on how real advertising actually works better than the direct marketing kind, read Don Marti‘s Targeted Marketing Considered Harmful. Then move on to the rest of Don’s growing medicine cabinet of direct marketing disinfectant for adverting.

Leave a Reply