A couple weekends ago I visited the graves of relatives and ancestors on my father’s side at Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx. All of them died before I was born, but my Grandma Searls and her sisters often visited there, and I thought, Hey, now that I’m in New York a lot, I should visit these dead folks. Grandma would like that. Here she is at at age three, in early 1886:

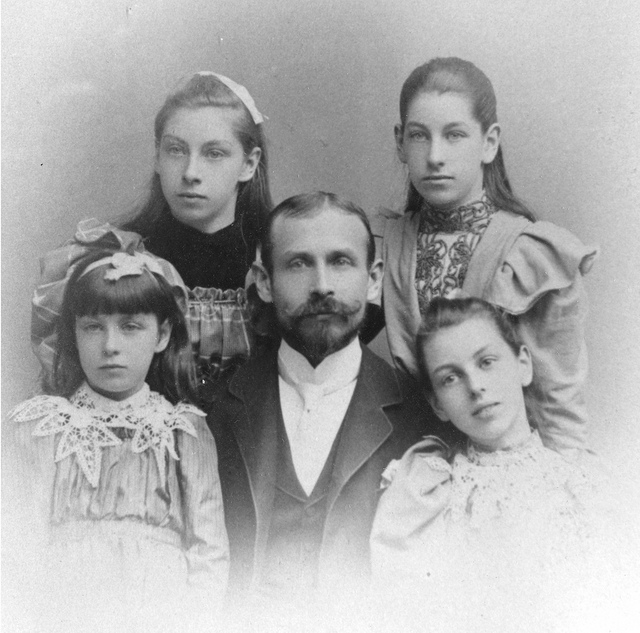

She was born Ethel Frances Englert, on November 14, 1882, the third of four sisters. Here they are with their dad, Henry Roman Englert, in 1894:

Grandma is the foxy one on the lower right.

Grandma is the foxy one on the lower right.

They lived here, at 742 E. 142nd Street in the South Bronx:

That row house was razed*, along with the rest of the block, to make room for what is now called “Old” Lincoln Hospital. These days an impoundment lot for towed cars reposes atop a hill formed by the imploded remains of the hospital. Amazingly, a lookup of the address on Bing Maps still goes to the same location, a century after these homes disappeared. Here’s how it looks now.

[Later…] * Big correction there! The row house may live! I found from the back of a photo that the house was on the south side of 142nd, west of Brook Avenue. Apparently the street numbering has changed since Victorian times.

While I can see some of those houses have been cleared away, Google Maps says 24 remain, starting here in this StreetView photo.

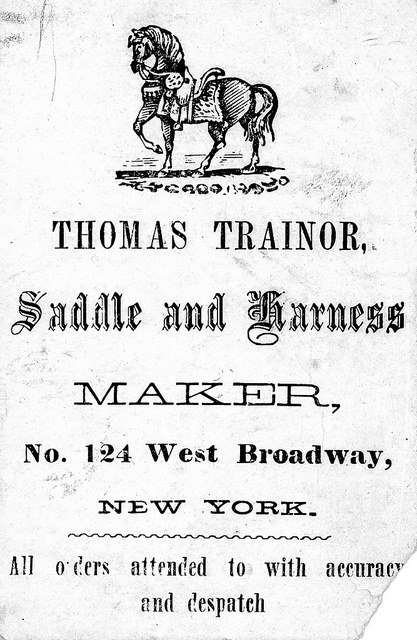

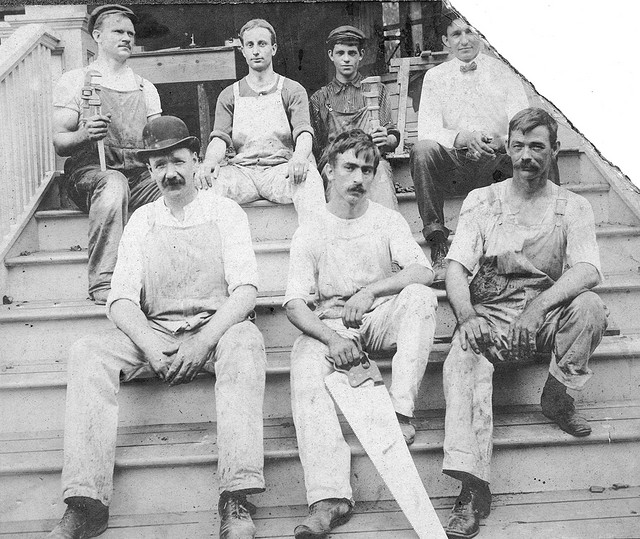

Henry was a son of Christian and Jacobina Englert, immigrants from Alsace-Lorraine, and head of the Steel & Copperplate Engraver’s Union in New York. His first wife, the four girls’ mom, was Catherine “Katie” Trainor, the daughter of Thomas Trainor, who emigrated from Letterkenny, Donegal, Ireland at age 15 in 1825, leaving six siblings behind. Thomas married Mary Ann McLaughlin of Boston, settled in New York, and made his living in the carriage trade:

He lived and died at 228 East 122nd Street in Harlem. He and his wife Anna (née McLaughlin), married at St. Peter’s in Manhattan produced seven children, of which Katie was the second. The others were Hanna, Ella, Margaret, Mary and Charles, who was killed in the Civil War. Family legend says Chartles ran away as a teenager to fight, and was shot carrying the Union flag. But he didn’t die then. The old man visited the kid in a Washington army hospital, barely recognizing his son through the boy’s thick red beard. On Christmas 1865 the Charles arrived home in a box.

Thomas, Charles and other Trainors are among the early plantings in Old Calvary Cemetery in Queens. At three million corpses strong, Calvary is New York’s largest. I’ve never been there, and I’ll bet almost nobody else has in over a century. (One exception: Aunt Catherine Burns, about which I say more below.)

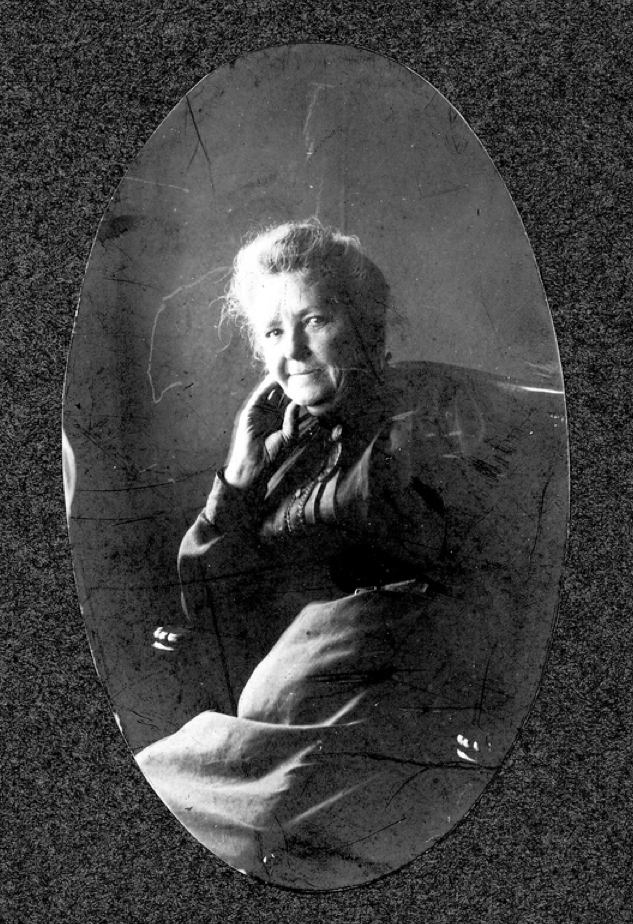

Katie’s sister Margaret, better known as “Aunt Mag,” or “Maggie,” was a favorite of the Englert girls and a source of gentle but stern family wisdom. A sample: “You’ve got it in your hand. Put it away.” Here she is:

Maggie was the only one of the Trainor kids to live a long life, dying in 1944. Katie died at 38.

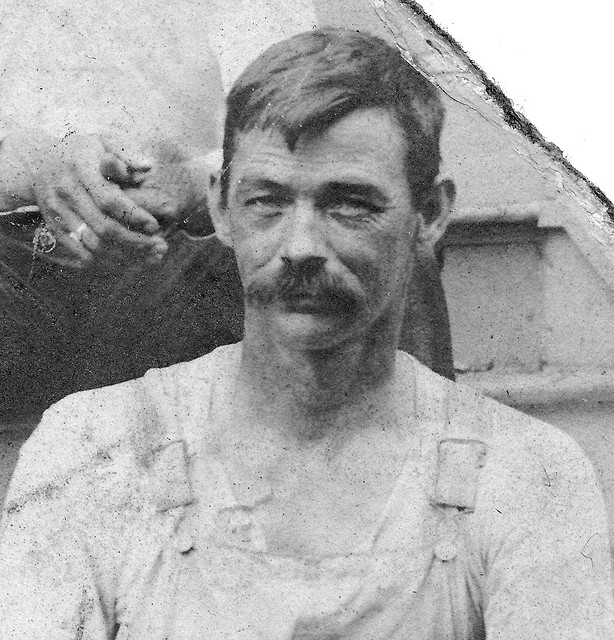

After Katie’s death, Henry married Tess Atonelle*, who had worked for the family. Here is Tess with Henry’s youngest brother, Andrew Englert:

Tess and Henry produced a number of additional offspring, of which only one was remembered often by Grandma and her sisters: Harry, who died at age 4 in 1901:

The next year Grandma married George W. Searls, my grandfather, who was 19 years older. George was, among other things, the head carpenter for D.W. Griffith, when Hollywood was still in Fort Leed. Here he is…

He built the family house at 2063 Hoyt Avenue, where my father and his two sisters were born and raised, and where my parents were hanging when I was born in 1947. The two upstairs floors were mostly rented out. Among guests and tenants passing through were Mary Pickford and Lillian Gish. Grandma preferred Lillian, finding Mary’s language too salty. Another was Edward Pierson Richardson, Sr., M.D., father of Elliot Richardson (who served as Commerce Secretary under Richard Nixon).

Grandma met Grandpa when she was working as cleaning help in a boarding house, where she found Grandpa sleeping. She was so attracted to the rugged carpenter that she bent over and kissed him. He woke up, pulled her down and kissed her back. Natural selection, I guess.

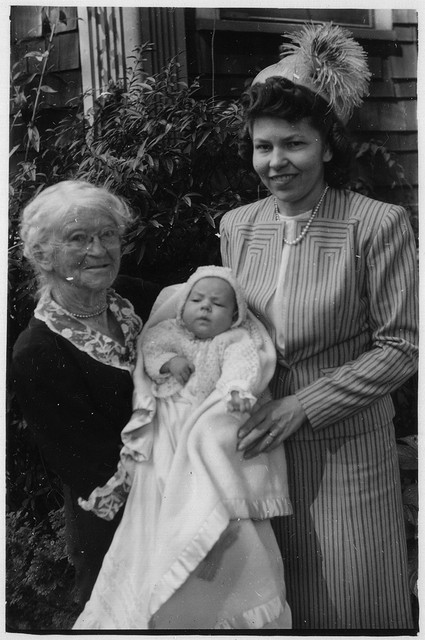

Grandpa died in 1934 at age 70 after catching erysipelas from a nail that scratched his face. If they had penicillin back then he might have lasted a lot longer. I remember his older sister, Eva Quackenbush, well. She was born in 1853, lived almost to 100 (she died in 1953), and told stories about what it was like when Lincoln got shot. She was 12 at the time. Here she is with Mom and the infant me:

I was lucky to know so many interesting characters born two centuries back, or close: stories of New York when the streets were all dirt and cobble, of the arrival of gas light, electricity, subways and trolleys, bridges and tunnels, cars and phones.

These people were living history books. Grandpa walked with a limp from a wound he got fighting in the Spanish-American War. Among many other achievements, he was foreman of the crew that built the Cyclone at Palisades Park: the scariest roller coaster in world history. Pop worked in that crew and was the first to ride it. Heres a photo he shot from the top:

Pop was a fearless dude.

Through the Depression Pop worked as a longshoreman in New York, helped build the George Washington Bridge, served in the Coastal Artillery and went to Alaska to build railroads. That’s where he met Mom. Then he re-enlisted to fight in World War II, where his last job was as General Eisenhower’s phone operator in Paris.

All four Englert girls were still going strong the whole time I enjoyed perfect childhood summers at the beaches and in the backwoods of South Jersey. Here they are on the Jersey shore in 1953:

They all spoke Bronx English, so the place where they stood was called ‘Da shaw.” It was also Mantoloking, not Point Pleasant. Just being historically accurate here.

What matters are the memories, which fade in life and disappear in death. I had hoped to bring some up, or to organize them in some way, when I visited Woodlawn.

It was less eerie there than blank: dead in several meanings of the word. Graves not “endowed” were marked by stones sinking into soft and hummocky glacial moraine. Who still remembers or cares about Henry Kremer (1853-1905) and his infant son, whose headstone is a few years away from burying itself? Those who cared enough to buy the stone are surely gone. How about Joseph Harper, who departed in 1897?

Bet nobody.

I took those photos while following a map made for me by my cousin, Martin Burns, who shares the same ancestors and relatives, and who had been there before with his mother, Catherine (named after her Irish grandma, Katie), who did much of the genealogical and photo-gathering work from which my research here benefits. She died not long ago in her late 90s. (If accident or disease doesn’t get us, we’ve got a nice portfolio of genes to work with here.)

I walked around for about half an hour. During that whole time, and while driving in and out of the cemetery, I saw nobody else, other than my wife, sleeping in the car. (She said this wasn’t her idea of a fun date.) Verdant and peaceful as it is, Woodlawn is abandoned by nearly all but the dead who reside there.

The Englert inhabitants of Woodlawn are spread across three grave sites. The fourth one on Martin’s map is the Knoebel’s. They’re the family into which Aunt Gene, Grandma’s oldest sister, married. She’s the second sister from the left in the beach shot, above. There are six graves in the Knoebel plot, which is the only one of the four that I found. Thirteen people were buried there. One, Aunt Gene, went in when she died in 1960, and came out a decade later, when she was moved to Fairview Cemetery in New Jersey.

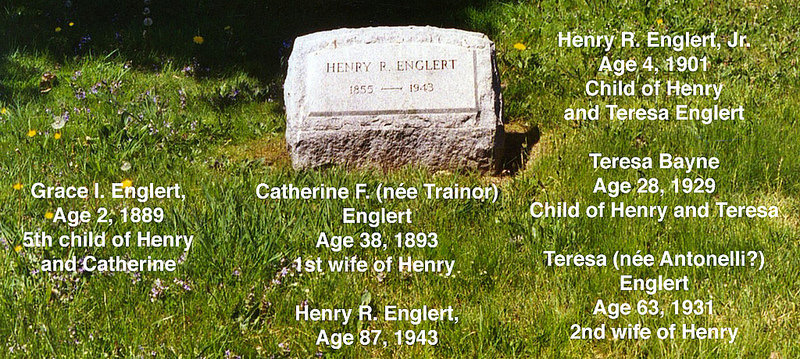

Christian and Jacobina are in an endowed plot, so their headstone stands upright. Here are aunt Catherine and cousin Kevin Burns (brother of Martin), standing behind it a few years back. There are three graves here, containing the bodies of seven people. I’ve listed them in this photo, by Martin. Four died young, and three lived full lives.

The single grave of Andrew and Annie Englert is unmarked, far as I know. (That’s Andrew next to Tess, above.) I didn’t find it. Nor did I find the grave of Henry Roman Englert, the root stock of most of the descendants I knew and heard about growing up. (I hadn’t yet posted the photos I got from Martin, so all I had to go by was a print-out of his map.)

After finding none of the Englert graves, I stood in one quiet spot and sent out a mental message to any ghosts who might be around, asking for a clue. I felt and heard nothing: clear evidence that the departed are truly gone.

Later, when I looked at these two photos, I saw that I was standing exactly on top of the graves of Henry, Katie, Harry, and several others. Here they are, in a photo Martin shot:

Several more things weirded me out, once I looked at the affidavit Catherine got from Woodlawn (or somewhere), listing the deceased under the grass there.

First was that a fifth Englert sister, Grace, existed. She was the youngest, died at age 2, and was buried here in 1889. Obviously my aunt Grace Apgar was named after this kid. But I never heard about the late baby Grace or forgot it. Either way, it was a surprise to learn she once walked on Earth, and lies in it here.

Second was that little Harry lay beneath both his older sister, who died at 28, and his mom, Tess, who died at 63. That all died young seemed even more tragic to me. (I’m five years older than Tess was when she went. “Young” is always less than one’s own age.)

Third was that old Henry R. got the only headstone, and it was probably not one he bought for himself. I’m sure it was put up after he died, I suppose by his surviving daughters.

Yet the site was visited often, way back when, I was told. Why did nobody ever mark them all? Or those in the other plots? Was it too expensive? And how did they know where to look without a marker of any kind?

I doubt I’ll ever know. Whatever the reason, it became clear to me that cemeteries are for one or two generations of living souls, and that’s it. If the dead remember the dead, they don’t do it here on Earth. Thanks to burial vaults (coffin containers) the dead don’t even serve as fertilizer.

At any moment there are better things for the living to do than dwell on dead people that nobody alive remembers or cares about. I’m probably wasting my time and yours by visiting the subject right now.

Yet I do feel a need to put what little I know about these people in pixels on the Web, rather than just on cemetery stones. I am sure, for example, that some Englert descendants — cousins I don’t know — will some day find this post and appreciate the efforts put into this accounting, mostly by Catherine and Martin.

Harvard, founded in 1636, is likely (I hope) to keep this blog up long after I’m gone; but even Harvard won’t be around forever. Everything dies. Rock under my ass in uptown Manhattan dates was formed about a half billion years ago. In another half billion years, life on Earth will be gone: burned away by a growing Sun.

Kevin Kelly once told me that in a thousand years, evidence of nearly everyone alive today will have disappeared. It’s a good bet.

Life is for the living. So is knowledge. All I’m doing here is contributing a little bit of both to the few people who might care — and acknowledging the love and caring that flows between people within and across all generations, nearly all of which are gone or not yet here.

Since I started with Grandma, I’ll close with her gravestone, in Brookside Cemetery in Englewood, New Jersey:

If we matter enough to be written about, our lives are framed by dates in parentheses. Grandma’s here is (1882 – When?) The answer is 1990, when she was nearly 108 years old. She is buried next to her husband George and her older daughter, Aunt Ethel M. Searls (1905-1969). Grandma’s other two kids were my father, Allen H. Searls (1908-1979), and Aunt Grace Apgar (1912-2013).

Ethel died of horrible medical treatment (including convulsive electroshock) for what was probably just depression. Though beautiful and brilliant, her love life went poorly, and she hit the glass ceiling as a regional office manager for Prudential Insurance Company — the highest position in the company held by a woman at the time.

Pop died of his fifth heart attack, all of which I am sure were caused by decades of heavy smoking. He and Mom are buried together in North Carolina. I visited Pop’s grave three times: 1) when he was planted in it; 2) with Mom on her 90th birthday; and 3) when she died a few months later. I haven’t been back since.

Grace died last December of being done. Until then she lived an active and wonderful life. You can see that in shots of her 100th birthday party, which was a gas. She lived in Maine and her body, like those of husband Archie and son Ron, was cremated, sparing us all the need to avoid visiting remains in gardens of stone where almost nobody goes — except once, when they die. Her ashes and Archie’s flank the large headstone that says SEARLS, six feet behind Grandma’s foot-stone in the photo above.

I’d like my body to be recycled. Just put it in the ground somewhere, to feed living things. These days they call that natural burial. But I’m in no rush. Too busy.

_______________

* Since Google finds approximately no families named Atonelle, and many named Antonelli (and a few named Atonelli), I suspect Atonelle is an error. So I’d welcome a correction.

Leave a Reply