Advertising used to be simple. You knew what it was, and where it came from.

Whether it was an ad you heard on the radio, saw in a magazine or spotted on a billboard, you knew it came straight from the advertiser through that medium. The only intermediary was an advertising agency, if the advertiser bothered with one.

Advertising also wasn’t personal. Two reasons for that.

First, it couldn’t be. A billboard was for everybody who drove past it. A TV ad was for everybody watching the show. Yes, there was targeting, but it was always to populations, not to individuals.

Second, the whole idea behind advertising was to send one message to lots of people, whether or not the people seeing or hearing the ad would ever use the product. The fact that lots of sports-watchers don’t drink beer or drive trucks was beside the point, which was making the brand familiar to everybody.

In their landmark study, “The Waste in Advertising is the Part that Works” (Journal of Advertising Research, December, 2004, pp. 375-390), Tim Ambler and E. Ann Hollier say brand advertising does more than signal a product message; it also gives evidence that the parent company has worth and substance, because it can afford to spend the money. So branding was about sending a strong economic signal along with a strong creative signal.

Plain old brand advertising also paid for the media we enjoyed. Still does, in fact.

But advertising today is also digital. That fact makes advertising much more data-driven, tracking-based and personal. Nearly all the buzz and science in advertising today flies around the data-driven, tracking-based stuff generally called adtech. This form of digital advertising has turned into a massive industry, driven by an assumption that the best advertising is also the most targeted, the most real-time, the most data-driven, the most personal — and that old-fashioned brand advertising is hopelessly retro.

In terms of actual value to the marketplace, however, the old-fashioned stuff is wheat and the new-fashioned stuff is chaff.

To explain why I say that, let’s start with two big value-subtracts of adtech: 1) un-clarity about where any given ad comes from; and 2) un-clarity about whether or not any given ad is personal.

For example, take the one ad that appears for me right now, on my Firefox browser, in this Washington Post story:

What put that ad there?

If I click on the tiny blue button on the upper right corner of the ad (called “Ad Choices,” which I’ll visit later), I get to a linkproof “About Google Ads” page, so I guess Google placed this one. The page mostly pitches Google advertising to potential advertisers, but also says “you may also see ads based on your interests and more.” How do they know my interests? By tracking me, of course. Did I ask for that, or know how the tracking happens? No.

But I also don’t know if this ad is based on tracking. In fact I suspect it is not, because the ad is nowhere near any interest of mine. It was the only ad that got past the tracking blockers I have operating right now on Firefox. Why? Not sure about that either. According to my Ghostery add-on, these entities are following me on the Washington Post site:

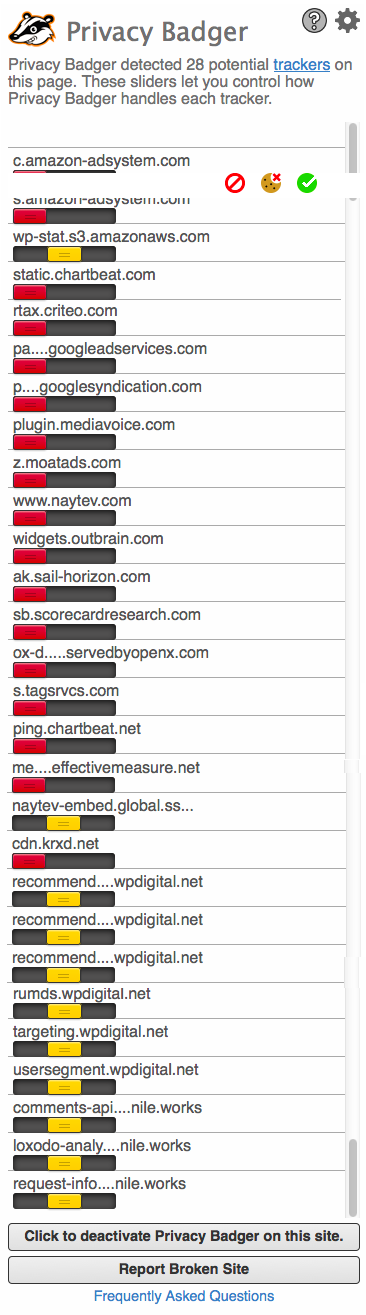

Google isn’t one of them. But then, Ghostery doesn’t see, or stop, as many trackers Privacy Badger, which I also have installed. Here’s that list:

Since I’m not currently running an ad blocker (e.g. Adblock Plus) on Firefox, but I am running Ghostery and PrivacyBadger (both of which follow and selectively valve tracking), I can assume that turned-off trackers causes some of the blank white spaces flanking editorial matter, each with the word “Ad” or “Advertisement” in tiny type.

Thus I suppose that the Google/Zulily ad got through because it either wasn’t tracking-based or because I have Ghostery and/or Privacy Badger set to wave it through. But I don’t know, and that’s my point. Or one of them.

Now let’s look at what I’m missing on that page. To do that, I just disabled all tracking and ad blocking on a different browser — Google’s Chrome — and loaded the same Washington Post page there.

It took twenty-seven seconds to load the whole page, including seven ads (which were the last things to load), over a fairly fast home wi-fi connection (35Mbps downstream).

Instead of the Zulily ad I saw in Firefox, there is an ad for the Washington Post’s Wine Club. A space-filler, I guess. Can’t tell.

Only one of the six other ads feature the little blue Ad Choices button. It’s one for the Gap. When I click on it, this comes up:

Then, when I then click on “Set your Ad Preferences,” I am sent to Gap Ad Choices, which appears to be a TRUSTe thing. The copy starts,

Interest-based ads are selected for you according to your interests as determined by companies such as ad networks and data aggregators. These companies collect information about your activity – like the pages you visit – and use it to show you ads tailored to your interests; this practice is sometimes referred to as behavioral advertising.

You can prevent our partner companies listed below from showing you targeted ads by submitting opt-outs. Opting-out will prevent you from receiving targeted ads from these companies, but you may continue to see our ads that are not shown through the use of behavioral advertising.

I’ve never heard of any of those companies, or those on the PrivacyBadger list, except for Google, Facebook, Amazon, Twitter and other usual suspects. Nor have you, unless you’re in the business.

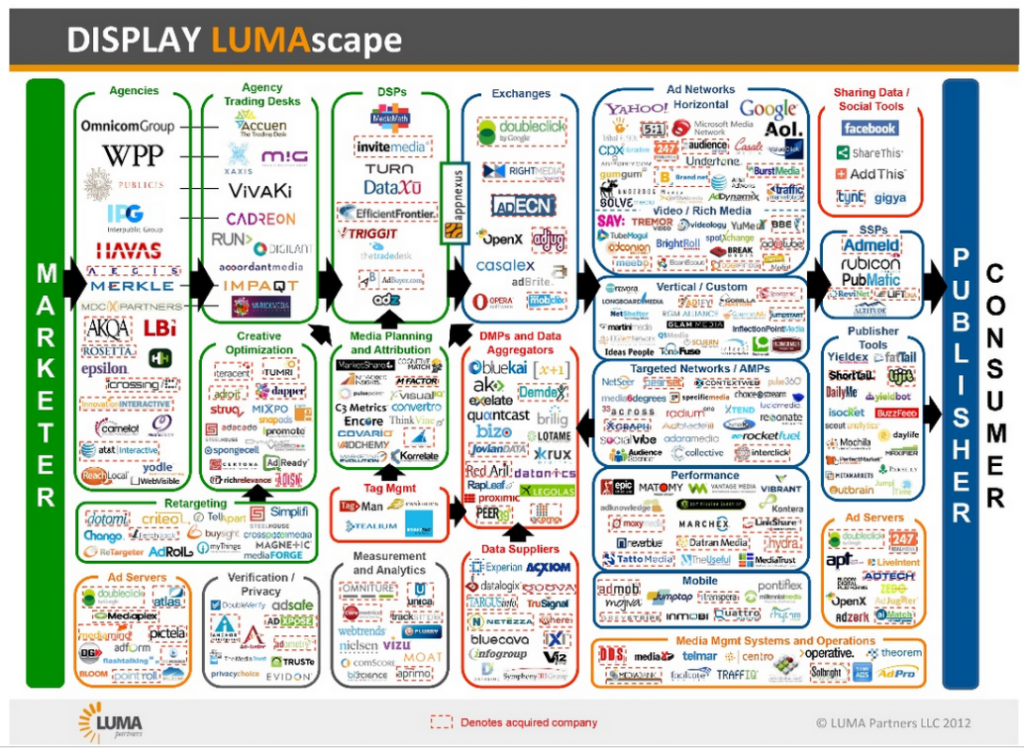

These companies are not brands, except inside their B2B sphere, which includes a mess of different breeds: trading desks, SSPs (Supply Side Platforms), DSPs (Demand Side Platforms), ad exchanges, RTB (real time bidding) and other auctions, retargeters, DMPs (Data Management Platforms), tag managers, data aggregators, brokers, resellers, media management systems, ad servers, gamifiers, real time messagers, social tool makers, and many more.

To see how huge this field is, visit Ghostery’s Global Opt-Out page, which companies that “use your data to target ads at you.” I haven’t counted them, but to get to the bottom of the list I had to page down twenty-eight times. And it’s still just a partial list. Lots of other companies, such as real-time auction houses, aren’t there.

If you’re game for more self-torture, check out LUMAscapes such as this one:

Or go to the master Ad Choices page. The headline there says “WILL THE RIGHT ADS FIND YOU?” — as if you want any ads at all. The copy below says,

Welcome to Your AdChoices, where you’re in control of your Internet experience with interest-based advertising—ads that are intended for you, based on what you do online.

The Advertising Option Icon gives you transparency and control for

interest-based ads:

- Find out when information about your online interests is being gathered or used to customize the Web ads you see.

- Choose whether to continue to allow this type of advertising.

Watch three short videos to learn how the Icon gives you control of when the right ads find you.

And if you want to go completely bonkers, try watching the videos, which feature the little ad choices icon as the “star” in “your personal ads.”

“Bullshit” is too weak a word for what this is. Because it’s also delusional. Disconnected from reality. Psychotic.

Reality is the marketplace. It’s you and me. And we have no demand for this stuff. In fact our demand, on the whole, is negative, for good reason. According to TRUSTe’s 2015 Privacy Index,

- 92% of consumers worry about their privacy online. The top cause of concern there: “Companies collecting and sharing my personal information with other companies.”

- 42% are more worried about their privacy than one year ago.

- 91% “avoid doing business with companies who I do not believe protect my privacy online.”

- 77% “have moderated their online activity in the last year due to privacy concerns.”

- 86% “have taken steps to protect their privacy in the last twelve months.”

- 63% “deleted cookies

- 44% “changed privacy settings”

- 25% “have turned off location tracking”

Ad blocking has also increased. According to PageFair’s latest report,

- “Globally, the number of people using ad blocking software grew by 41% year over year.” (Q2 2014 to Q2 2015.) In the U.S. the growth rate was 48%. In the U.K. the rate was 82%.

- In June 2015 “there were 191 million monthly active users for the major browser extensions that block ads.”

I should pause here to add that I use four different browsers on this laptop alone, and make it my business (as the chief instigator of ProjectVRM) to try out many different VRM (vendor relationship management) tools and services, including those for privacy protection, among which are tracking protection and ad blocking systems. These include Abine, Adblock Plus, Disconnect, Emmett‘s Web Pal, Ghostery, Mozilla’s Lightbeam, PrivacyFix, Privowny and others you’ll find listed here. I switch these on and off and use them in different combinations to compare results. The one thing I can say for sure, after doing this for years, is that it’s damn near impossible for any human being — even the geekiest — to get their heads around all the things adtech is doing to us, through our browsers and mobile apps, or how all the different approaches to prophylaxis work, especially if more than one is working at the same time in a browser. The easiest thing for everybody is to install (or switch on) a single ad and tracking blocker and be done with it. Which is exactly what we’re seeing in the research above.

Another delusion by the “interest-based advertising” business is the belief that we “trade” our personal data for the goods that advertising pays for. In October 2010 John Battelle wrote, “the choices provided to us as we navigate are increasingly driven by algorithms modeled on the service’s understanding of our identity. We know this, and we’re cool with the deal.” I responded,

In fact we don’t know, we’re not cool with it, and it isn’t a deal.

If we knew, the Wall Street Journal wouldn’t have a reason to clue us in at such length.

We’re cool with it only to the degree that we are uncomplaining about it—so far.

And it isn’t a “deal” because nothing was ever negotiated.

But adtech grew like crazy, rationalized by the faith John summarized. Then, in June of this year, came The Tradeoff Fallacy: How Marketers are Misrepresenting American Consumers and Opening Them Up to Exploiitation, a report from the Annenberg School for Communication of the University of Pennsylvania. In it Joseph Turow, Michael Hennessy and Nora Draper say that’s not the case. Specifically,

…a majority of Americans are resigned to giving up their data—and that is why many appear to be engaging in tradeoffs. Resignation occurs when a person believes an undesirable outcome is inevitable and feels powerless to stop it. Rather than feeling able to make choices, Americans believe it is futile to manage what companies can learn about them. Our study reveals that more than half do not want to lose control over their information but also believe this loss of control has already happened.

And it isn’t just about “giving up” data. It’s about submitting to constant surveillance by unseen entities, and participating, unwillingly, in what Shoshana Zuboff calls surveillance capitalism. This —

…establishes a new form of power in which contract and the rule of law are supplanted by the rewards and punishments of a new kind of invisible hand…

In this new regime, a global architecture of computer mediation turns the electronic text of the bounded organization into an intelligent world-spanning organism that I call Big Other. New possibilities of subjugation are produced as this innovative institutional logic thrives on unexpected and illegible mechanisms of extraction and control that exile persons from their own behavior.

And yet, scary as it is, Big Other is limited by three realities that are now beginning to become clear through the veil of adtech’s delusions.

First is the paradox Don Marti isolates in Targeted Advertising Considered Harmful: “The more targetable that an ad medium is, the less it’s worth…For targeted advertising, it’s damned if you do, damned if you don’t. If it fails, it’s a waste of time. If it works, it’s worse, a violation of the Internet/brain barrier.”

Second is adtech’s belief that we are nothing but consumers, and that all are ready at all times to hear a sales pitch — especially a personalized one.

Third is that this actually works, when most of the time it does not.

For example, I just looked up Mt. Pisgah at maps.google.com. In “search nearby” (which Google volunteers as a default search choice, along with a picture of a pizza), Google’s search algorithm assumes that I’m looking, by default, for hotels and restaurants. But what if I’m looking for hiking or biking trails, or something else that costs no money? No luck. Google instead gives me a hotel, a lake and another wilderness area. In fact Google — which one might think knows me well, since I’ve been a user of their services since the beginning, and has me logged in on Chrome — has no idea why I want to look up that mountain. (In fact it was to illustrate this point, for this essay. Nothing more.)

I just went back through the last seven days of my browser usage on Firefox, Chrome, Safari and Opera, to see if there is any hint about anything I might have wanted to buy. Out of many hundreds of pages I’ve visited, there is a single hint: a search I did for a replacement remote control for my sister’s Sansui TV. (I didn’t buy it, but I did email her a link.)

Even Amazon, which deals with us mostly when we are in shopping mode, constantly promotes stuff to us that we looked for or bought once and will never buy again. (For years after my grandson had moved past his obsession with Thomas the Tank Engine, Amazon pushed Thomas-like merchandise at me.)

Worse, Amazon constantly mixes wheat and chaff banner ads, so you don’t know whether what you’re seeing is there because Amazon knows you, or because it’s blasting the same promo at everybody.

This has been the case lately with Amazon’s “Home Essentials” banner, “presented by Pure Wow.” If you click on the Pure Wow logo, you get sent to a page that identifies the company as “a women’s lifestyle brand dedicated to finding unique ways to elevate your everyday.” Is Pure Wow a division of Amazon? Is it a company that paid Amazon to place the ad as a branding exercise? Does Amazon think I’m a woman? WTF is actually going on?

Fortunately, it’s possible to tell, by looking at Amazon through a browser uncontaminated by cookies or spyware. (In my case that’s Opera.) This is how I determined that Pure Wow is a simple brand ad, blasted at a population. In other words, wheat. But the fact that it’s hard to tell is itself a value-subtract, for Amazon and Pure Wow as well as for the rest of us, illustrating Don Marti’s earlier point, that the value of a medium varies inversely with its target-ability. In other words, because Amazon is targetable, the ads it runs are worth less than they would be if it weren’t.

Because marketing is now so totally data-driven, and it is possible for marketing machinery to snarf up personal data constantly and promote at people in real time, the whole business has become obsessed with metrics, rather than the marketing fundamentals taught, for example, by Theodore Levitt and Peter Drucker.

Nearly the entire commercial Web — the part that’s increasingly monetized y tracking-based advertising — is so high from smoking its own exhaust that it actually believes that we are in shopping mode, all the damn time.

These intoxicated marketers completely miss the fact that 100% of the time we are dealing with stuff we’ve already bought, and often need serviced. (Like my sister with the lost remote control.)

Thus we have the strange irony of marketing talking about “brand value,” “loyalty,” and “conversation” while doing almost nothing to serve actual customers who need real help, besides answering complaint tweets and routing inquiries to robots and call centers (which are increasingly the same thing).

My point here is that giant companies — the Big Other — really think homo sapiens is homo consumerus, which is a category error of the first water.

Worse, it’s an illusion. Getting would-be oppressors to assume we are doing nothing but buying stuff all the time is one of the all-time-great examples of misdirection.

And think about what happens when personalized advertising works — for example, when it serves up an ad we can actually use. The actual value of that ad is still compromised by the creepy suspicion that we’re seeing it because we’re being followed, without permission, using who-knows-what, based on unwanted personal data leakage through tracking beacons sucking like leeches on our virtual, and put there flesh by parties that may not be Google or others who want to point us to the nearest pizza joint when we just want to know what exit to take.

Kapersky Labs calls the leeches “adware.” Specifically, adware is the payload of cookies, programs and other code inserted into your browser, your computer and your mobile device, mostly without your knowledge or permission. The industry and its associations (such as the IAB and the DAA) say adware is all about giving you a better “advertising experience” or whatever. But to the Kaperskys of the world, adware is an attack vector for bad actors such as malware spreaders — all looking to siphon money off an easily gamed system, often by planting hard-to-find bots and other malicious files inside the hardware and software through which we live our digital lives. Kapersky’s 2014 report, for example, is full of arcana that’s hard for civilians to understand, but is worth reading just to get an idea of how very bad this problem is for everybody. Here’s a sample:

Almost half of our TOP 20 programs, including the one in first place, were occupied by AdWare programs. As a rule, these malicious programs arrive on users’ computers alongside legitimate programs if they are downloaded from a software store rather than from the official website of the developer. These legitimate programs might become a carrier for the AdWare-module: once installed on the user’s computer it can add advertising links to browser bookmarks, change the default search engine, add contextual advertising, etc.

Here is one example of one piece of malware at work:

The Trojan-Clicker.JS.Agent.im verdict is also connected to advertising and all sorts of “potentially unwanted” activities. This is how scripts placed on Amazon Cloudfront to redirect users to pages with advertising content are detected. Links to these scripts are inserted by adware and various extensions for browsers, mainly on users’ search pages. The scripts can also redirect users to malicious pages containing recommendations to update Adobe Flash and Java – a popular method of spreading malware.

No wonder security expert T.Rob Wyatt says Online advertising is the new digital cancer. He explains,

I often refer to AdTech as the Research & Development arm of organized cybercrime. The criminals no longer have to spend money inventing new ways of penetrating the mobile device or PC since they can purchase a highly targeted ad for mere pennies instead. Thanks to very effective personalization capabilities delivered by ad networks, the cybercriminals can slice and dice their content and tailor the malware for specific audiences.

There are many ways to personalize content. For instance, do you ever wonder why we so much email spam is obvious? Spam is often riddled with misspellings, bad grammar, and other glaring clues as to its malicious intent. We think “those must be some really dumb spammers” as we click delete. Who would fall for that, right? Actually, that is intentional. People who are so eager for the promised product that they are willing to overlook those obvious clues are self-selecting as the most gullible targets, and therefore the most lucrative. Malvertising relies on a similar filtering mechanism: Anyone NOT using ad blockers is self-selecting into the cybercriminal’s target pool.

There are many names for digital advertising’s chaff. “Interest-based advertising” is the Ad Choices conceit. Inside the business, “adtech” and “programmatic” are two common terms. Kapersky uses “adware.” Don uses “targeted.” I like “tracking-” or “surveillance-based.”

The original name, however, before it began to be called advertising, was direct response marketing. Before that, it was called direct mail, or junk mail.

Direct response marketing has always wanted to get personal, has always been data-driven.

Yes, brand advertising has always been data-driven too, but the data that mattered was how many people were exposed to an ad, not how many clicked on one — or whether you, personally, did anything.

And yes, a lot of brand advertising was annoying, and always will be. But at least we knew it paid for the TV programs we watched and the publications we read.

So now is the time to separate advertising’s wheat from its chaff, in the place where it’s easiest to do, and where it counts most: in our own browsers, apps and devices. It’s much easier to defeat the problem ourselves than by appealing to policy-makers and the industrial giants that rule the commercial Web. And we’re already part way there, thanks to friendly makers of browsers, extensions and add-ons that are already on the case.

Hence…

An easy solution

All we need is a way to see what’s wheat and what’s chaff, and to separate them as we harvest content off the Web.

In agriculture this is done with a threshing machine. On the Web, so far, it’s done with ad and tracking blockers. All we need to do next is adjust our browsers and/or blockers to allow through the wheat. (Or to continue blocking everything, if that’s our preference. But I think most of us can agree that encouraging wheat production is a good thing.)

For that we need to do just two things:

- Label the wheat on the supply side, and

- Be able to pass through wheat on the demand side.

This can be done with UI symbols, and with server- and browser-based code.

By now it is beyond obvious that the chaff side of the chaff-obsessed advertising business won’t label its ads except with fatuous nonsense like the Ad Choices button. They can’t help us here.

Nor can attacking problems other than tracking. Not yet, anyway.

This is why well-meaning efforts such as AdBlock Plus‘s Acceptable Ads Manifesto can’t help. While everything the Manifesto addresses (ads that are annoying, disruptive, non-transparent, rude, inappropriate and so on) are real problems, they are beside the point.

As T.Rob puts it in Vendor Entitlement Run Amok, “My main issue with vendors turning us into instrumented data sources isn’t the data so much as the lack of consent.”

If we consent to wheat and block the chaff we solve a world of problems. Simple as that.

And we’re the only ones who can do it.

In her Black Hat 2015 keynote, Stisa Granick says,

Now when I say that the Internet is headed for corporate control, it may sound like I’m blaming corporations. When I say that the Internet is becoming more closed because governments are policing the network, it may sound like I’m blaming the police. I am. But I’m also blaming you. And me. Because the things that people want are helping drive increased centralization, regulation and globalization.

So let’s not just blame ourselves. Let’s fix the problem ourselves too, by working with the browser and ad and tracking blockers to create simple means for labeling the wheat and restricting our advertising diet to it.

And believe me, there are still plenty of creative people left on the old wheat-side advertising business — on Madison Avenue, and in the halls of AdAge and MediaPost — to rally around the idea of labeling the good stuff and letting the bad stuff slide.

By harvesting wheat and threshing out chaff, we also encourage good advertising and re-align it with good editorial (a word I prefer to “content,” which always sounds like packing material to me). We may not like all the ads we see, but at least we’ll know they have real value — to the sites we read, the broadcasts and podcasts we watch and listen to, and to the ad-supported services we depend on.

Then, for those of us who want or welcome certain kinds of tracking, we can also create useful flags for those as well, and consent that’s worthy of the noun.

But let’s start where we can do the most good with the least effort: by threshing apart advertising’s wheat and chaff.

Bonus links:

- Everything by Bob Hoffman and Don Marti

- The coming collapse of surveillance marketing

- On taking personalized ads personally

- Thoughts on tracking-based advertising

- Tracking and Profling Run Amok

- What They Know (a landmark series in The Wall Street Journal, which ran from 2010 to 2013).

- The Data Bubble

- The Data Bubble II

- Making business more human

- Adblocking could be the savior of high-quality journalism

- I miss the days of expensive advertising

Leave a Reply