![]() In this post I respond in detail to assertions made in a pair of pro-adtech pieces: Advertiser’s Mandate In The Age Of Ad Blocking: Blend In, by Pat LaPointe in MediaPost; and Welcome to hell: Apple vs Google vs Facebook and the slow death of the web, by Nilay Patel in The Verge.

In this post I respond in detail to assertions made in a pair of pro-adtech pieces: Advertiser’s Mandate In The Age Of Ad Blocking: Blend In, by Pat LaPointe in MediaPost; and Welcome to hell: Apple vs Google vs Facebook and the slow death of the web, by Nilay Patel in The Verge.

First, Pat LaPointe—

Consumers are increasingly constructing their own digital “content cocoons.”

“Cocoon” is a vivid metaphor, and makes sense from the adtech point of view. It also doesn’t position self-protecting people and their tech as enemies that need to be fought, which is good. But it’s not what people think they are doing when they control their lives, online or off. So let’s be clear here. People only want two things when they block ads and tracking:

- Freedom from annoyance, and

- Privacy.

In the physical world they get those from the technologies we call clothing and shelter. There are no equivalents yet online. But ad and tracking blocking point in a civilized direction. More about this under the next item.

From their Facebook network to apps for their favorite stores, consumers exert more control over the content and messages they are exposed to than any time in history.

First, we aren’t just “consumers,” which Jerry Michalski calls “gullets with wallets and eyeballs.” Nearly everything that makes us human is not reducible to an appetite for “content.” And our gullets (which yes, we do have) are gagging on advertising we already hated and are being forced by adtech to hate even more.

Second, people don’t exert control over content and messages with their “Facebook network” (whatever that is) or their “favorite stores” (which, even if they have them, are little more than one app among many on their phones). They exert control with technologies that are theirs, even if they only rent them — and that control is indeed increasing. Here’s how:

In the physical world we exert control our ourselves and our interactions with others through many technologies for both selective disclosure (clothing, shelter) and engagement (wallets, purses, cars).

In the online world the equivalent to these are browsers, email clients, computers, mobile devices and the apps that run on them. The fact that all those things are infected with spyware and controlled to a high degree by giant companies (notably Apple and Google) does not mean they are not under personal control. It means they are compromised. This is why people want to cure the infections in their mobile devices and increase their control.

What we want most as free and independent human beings is agency: the ability to act with full effect. We know what this feels like in the physical world, and we are learning what this feels like in the virtual one, starting with ad and tracking blocking, which adds a higher degree of privacy to our browsers . (Apple is also on this case as well, by the way. Read more here.)

Now consumers are curating their advertising experiences, as well with ad blocking.

“Curating” is a strange word for what ad blocking does, which is actually prophylaxis.

As a result, there is a battle between advertisers that try desperately to get their message in front of the right consumers, and the consumers who work hard to not be exposed to things they’re not interested in.

That’s half-right. The battle is definitely going on, but what people are mostly not interested in — and hate at this point — are advertising and spying.

Apple will offer an ad blocker in its newest OS.

Actually, it’s called Content Blocking, and it’s only for supporting developments of apps that add selective forms of blocking to the Safari browser on iOS 9. Still, it’s one form of chemo for the cancer of adtech. (Bonus link on 18 September. Evidence of what I said here.)

Ad blocking will hardly kill advertising; it’s what drives the Internet.

Two errors here:

First, ad blocking doesn’t kill advertising. It does for advertising what bug repellent does for bugs.

Second, nothing “drives” the Net, which is an agreement among network operators about how data gets passed between end points. True, at this moment in time there are a lot of ad-supported sites on the Web, but those are neither the Net nor any more permanent than a mobile home park.

Yet, it is a growing threat to the way marketers have traditionally approached marketing – to push mass messages out through standard channels and hope that the right audience is exposed to enough to drive revenue.

Correct.

The rise in ad blocking is a sign that advertisers need to re-engineer their dialogue with consumers to be a relevant part of consumers’ “content cocoons.”

Almost none of the dialogue between companies and customers is conducted within advertising, which has been engineered from the start as a one-way thing. Even direct response marketing, the direct ancestor of adtech, was never about “dialogue.” That job belonged to other corporate functions, especially sales and service.

Consumers Assume You Know What They Want.

No they don’t. They assume you know shit, want to spy on them, and tospam them with ads that are unwanted 100% of the time, irrelevant 99.x% of the time, and creepy the .x% of the time they’re on target.

Consumers have been leaving a trail of digital breadcrumbs online for years — from searches and shopping info to social media comments to survey responses.

True. But that is not an invitation to spy on them, or to intrude into their lives with presumptuous and unwelcome messages.

I also suspect that much of what adtech sees as a crumb trail is really what they harvest by surveillance tech.

Many marketers have collected the information, but have done a less-than-stellar job of putting the picture together.

“Collected” makes it sound like marketers just follow people around the digital world, collecting leftover debris (which they do), rather than spying on them constantly with tracking files, beacons and other invasive tech that no person asked for and few welcome.

As for “less than stellar,” yeah.

With the rise of content cocoons, it is vital that marketers work to assemble better pictures of their consumers…

Do customers want marketers to have “better pictures” of them? Really? Most customers want the companies that serve them to have the information necessary for that service, but not much if anything more.

(An aside: most marketers are not involved in adtech and have a respectful regard for people and what they want out of relationships with the companies that serve them. I’m debating here with the breed of marketers whose main interest is tracking people and personalizing advertising for them, whether they like it or not.)

…or risk losing consumer contact completely.

This is delusional marketing vanity.

There are a zillion ways for a company to connect with customers, starting with sales and service people and systems. If marketing loses “contact” based on spying, it’s little if any loss (and mostly a relief) for the individuals being spied on, and possibly no loss at all for the company doing the marketing, given better ways to actually connect with customers.

As consumers exert more control over their digital experiences, they actually expect relevance, particularly on mobile.

No they don’t. At least not from advertising, which is irrelevant or off-base most of the time.

We also got along fine without advertising on phones from 1876 to 2008, and as we get more control over our mobile devices, expect advertising to be the first thing we’ll wipe off them.

This means doing more than simply retargeting shopping or search behaviors. As consumers continue to wield more control over their experiences, the imperative to meet their expectations rises considerably.

It is insane (meaning disconnected from reality) to assume that more than a small minority of people will want ads of any kind of their phones, much less more relevant ones.

Even Google Maps’ ads in the results of a search for “coffee shops” are rarely more helpful than the tiny red dots that mean “look at this one too.”

Consumers expect that marketers are up to date. (e.g. don’t market that shirt to me, I just bought it!)

No they don’t. They expect to see retargeted ads for what they just bought, up to months or years after they bought it. Unless they use an ad or tracking blocker.

Consumers expect that marketers know why they are behaving in a certain way. (e.g. I bought a Honda because it is reliable, not because it’s cool.)

No, they expect marketers to know nothing other than how to push crap at them constantly, based on scant, inaccurate, irrelevant and abundant data that’s harvested by unwelcome surveillance.

Consumers expect that marketers know who they are intrinsically. (e.g. I am interested in innovative and unique electronics, not deals on last-years’ models.

No, they expect marketers to want to know all kinds of crap about people, by every means possible, regardless of the manners (or even the legality) involved, and to assume what Nixon’s team of creeps (way back when) called “plausible deniability” when asked if they know a person’s actual identity.

How can marketers meet these demands?

Demands? Please.

By understanding what drives a consumer to create their content cocoon…

It’s simple. They want you to go away. Please. Go away.

…and blending in.

You mean camouflage? When hiding already isn’t working?

First, marketers need to take a more deliberate targeted approach.

Or maybe a less targeted one. See Separating Advertising’s Wheat and Chaff.

Ad blocking happens both because of irrelevant generic messages but also because of creepy or badly targeted messages.

No, it happens because millions of people don’t like being tracked and targeted — or any advertising at all.

Marketers that go the extra mile will find a few distinct audiences more likely to find the message relevant, and may decide to leave one or more groups out rather than risk alienating them.

Maybe. Good luck with that.

For this shift to happen, the metrics of success have to change from generating “impressions” to building “engagement” in the form of access, sharing, or exploration.

Actually, generated impressions have built brands from the beginning. Heard of Coke? McDonalds? Kodak? (Well, at least the branding worked.) The thing is, those impressions did not carry the burden of “engagement,” and that was their charm. They just impressed viewers, listeners and readers. Simple, and effective.

You want engagement? Try doing brand ads that are so good they go viral and the market talks to itself about them without additional help from marketing dweebs. Example: Volkswagen of America’s TV ads with the old ladies.

Marketers can look at how much consumers opt in, use apps, read email, shop, or how they search for key topics.

This is the sound of marketing smoking its own exhaust.

People don’t want to be looked at, unless they have a damn good reason to trust who or what is looking.

Next, marketers need to match their tempo to a consumer’s activity levels.

This tells me something is for sale. Being a curious type, I see Pat LaPointe is the Chief Growth Officer for Resonate, which “makes marketing more relevant by uncovering why people do what they do.” I’d rather stay covered, thank you. So would everybody else who would like to block whatever it is Resonate does to uncover them.

Consumers don’t care if email, advertising or mobile coupons came from three different divisions of a company, they see it as one brand conversation.

Wrong. If people have a real relationship with a company, they want it to be with sales or service. That’s it.

For example, I have a great relationship with the service department of East Coast Volkswagen in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey. I’m on a first-name basis with the guys there, who know their shit and have earned my trust and affection by treating us honestly and well. I’ve also seen and received the dealership’s marketing materials, and couldn’t care less about them. What matters is who I get on the phone when I need them, and how I’m treated. That’s it, for approximately everybody who owns a car.

If companies took half of what they’re wasting on adtech and put it into service improvements, they would have better (and more real) conversations with customers, and earn genuine loyalty, rather than the coercive kind that comprises every “loyalty program.” (If you need a program to obtain loyalty, you’re not eligible for the real thing.)

Finally, marketers must treat each message as if it’s part of a consumer’s own curated online persona.

More smoked exhaust.

Who wants any company’s message to be part of their “curated online persona,” whatever that is?”

Marketers must improve their ability to interpret the breadcrumbs that consumers leave online to build the right picture of each consumer because the consequences of alienation are so much higher than before.

What’s causing that alienation? Hmm?

And how about giving us back the “crumbs” you’ve collected from us? Betcha we can do more with it than you can. (We did with computing, networking, and much else.)

Every layer of the cocoon makes it harder and more expensive for marketers to break-thru to engage the consumer.

It’s not a cocoon. It’s my house. Stay out of it.

Now Nilay Patel—

So let’s talk about ad blocking.

Yes, let’s.

You might think the conversation about ad blocking is about the user experience of news, but what we’re really talking about is money and power in Silicon Valley. And titanic battles between large companies with lots of money and power tend to have a lot of collateral damage.

Pure misdirection. He’s saying, “Don’t look at what people are doing to control their experience of the Web. Look over here at what the big bad companies are doing. That’s what ad blocking is all about.”

And yeah, what big companies do is always interesting when one of them is starting a fight. (Which Apple in particular is doing.) But ad blocking is what a large and growing percentage of individual human beings are doing to repel intrusive files and a Niagara of ads. That’s a serious topic, and needs to be talked about. Which now we’re not.

Unfortunately, the ads pay for all that content…

A lot, but not all. There are plenty of publishers and broadcasters that get along fine without advertising. HBO, Netflix, Consumer Reports and this blog, for example.

…an uneasy compromise between the real cost of media production and the prices consumers are willing to pay…

Stop. The commercial Internet is just 20 years old (dating from the end of NSFNet, the last holdout against commercial traffic within the Internet). We’ve hardly begun to experiment with all the different ways things can be funded, and ways people can signal their willingness to pay. And as long as only the sell side can do the signaling, the best we’ll get from the buy side is crude means of saying “Nyah,” such as ad blocking.

…that has existed since the first human scratched the first antelope on a wall somewhere.

Hyperbole. Advertising by that name has only been around since the 19th Century. The term “brand” has only been around since the ’30s, when Madison Avenue first became advertising’s metonym. Direct response marketing, of which tracking-based adtech is a breed, is much younger, and descended from direct mail, first called “junk mail” in 1954.

Alas, direct response marketing, which is entirely data driven and wants to get personal at nearly all times, has body-snatched Madison Avenue and the rest of advertising, so distinctions between the creepy kind based on tracking and the non-creepy kind (which just wants to be seen or heard) is all but lost. (I expand on the difference in Separating advertising’s wheat and chaff.) Thus adblocking kills both rather than just the most objectionable kind.

Media has always compromised user experience for advertising…

If we had to stick with “always,” we wouldn’t have the Net. Why do things only the old way?

And speaking of the Net, here we have the first medium where individuals have serious power and control. And they are exerting it, finally, with ad and tracking blockers, which send a clear signal — one that media like The Verge should heed.

… that’s why magazine stories are abruptly continued on page 96, and why 30-minute sitcoms are really just 22 minutes long.

Those ads were (and still are) real ads, not adtech. Readers and viewers knew where they came from and what they were doing there. They also weren’t personal, or based on surveillance. On pubs such as The Verge, it’s not clear with any ad whether or not it’s based on tracking the reader. Or why, exactly, any ad is where it is, or what mechanisms placed it there. (In fact, it’s a good bet most ads on The Verge are based on surveillance, as we’ll see below.)

It’s essential to remember the differences between advertising online and off. Ari Rosenberg does a good job of that in Why Does Randall Rothenberg Still Have a Job?. A sample:

Ad blocking is not a universal media problem — it’s an online advertising problem. TV viewers give television ads a shot — just ask Geico, IBM and Direct TV. Moviegoers don’t sit outside a theater when ads are playing. Magazine readers don’t turn away from ads when they turn the page. Even radio ads get a listen. Ad blocking is an online advertising problem we created — and one we deserve.

A successful publishing formula has a pecking order. Consumer needs are paramount to those of the advertiser. When this relationship is constructed that way, consumers accept advertising as part of this arranged marriage. Instead, the IAB has promoted and supported ad policies that put advertisers on a pedestal and the needs of consumers in the servants’ quarters. Blocking ads is the consumer’s way of asking for a divorce.

Those are points @AdContrarian and @DMarti have been making for years. Good to see it coming from the inside of adtech. (I just wish Ari hadn’t wrapped his points inside a slam on IAB chief Randall Rothenberg. Randall has been in at least some degree of sympathy with what I’ve been saying here, for years, which is why he invited and paid me, twice, to give talks to IAB conferences. I didn’t pull any punches at either of them, but I also made no difference. Adtech is a mania, and you can’t talk a mania down. You just have to let it fail.)

Media companies put advertising in the path of your attention, and those interruptions are a valuable product.

To them. Not to us, except on rare occasions when we actually do click on them (which runs at fractions of 1% of the time).

Your attention is a valuable product.

Yes, to us. That’s why we care how we spend it. Clearly a lot of us would rather not spend it watching pages slowly load behind tracking files and ads based on that tracking.

Speaking of which, check out Les Orchard‘s The Verge’s web sucks. He begins,

So, I’ve been a big fan of The Verge, almost since day one. It’s a gorgeous site and the content is great.

They’ve done some amazing things with longform articles like “What’s the deal with translating Seinfeld” and “Max Headroom: the definitive history of the 1980s digital icon“, and the daily news output is high quality.

But, I have to say, reading Nilay Patel‘s “The Mobile Web Sucks” felt like getting pelted by rocks thrown from a bright, shiny glass house.

And then he uses dev tools to look into what The Verge loads into your browser every time you visit. Simply put, it’s a mountain of spyware. More about that below.

…taking money and attention away from the web means that the pace of web innovation will slow to a crawl. Innovation tends to follow the money, after all!

Not always. The Net, the Web, email, Linux, Wikipedia and countless open source code bases (on which we all depend) have come to the world from geeks working for needs other than money.

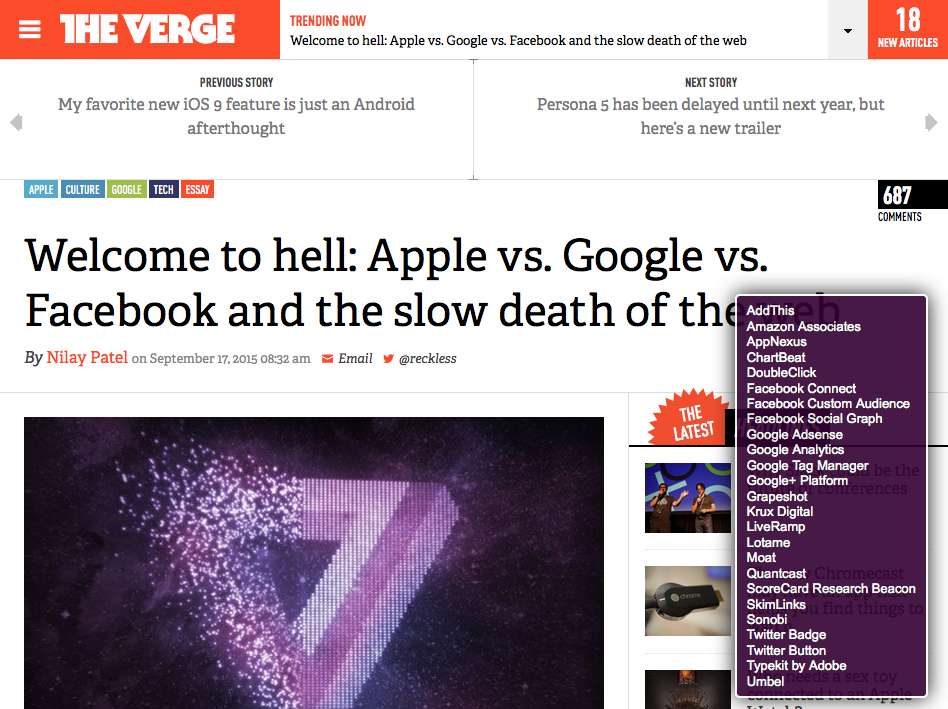

The rest of Nilay’s piece does a good job of laying out the current and coming battles between Google, Apple, Facebook and others. But if he really wants to talk about ad blocking (as he says at the top of his piece), how about looking at reasons The Verge gives users for using them? For example, here is what Ghostery says loads along with Nilay’s story:

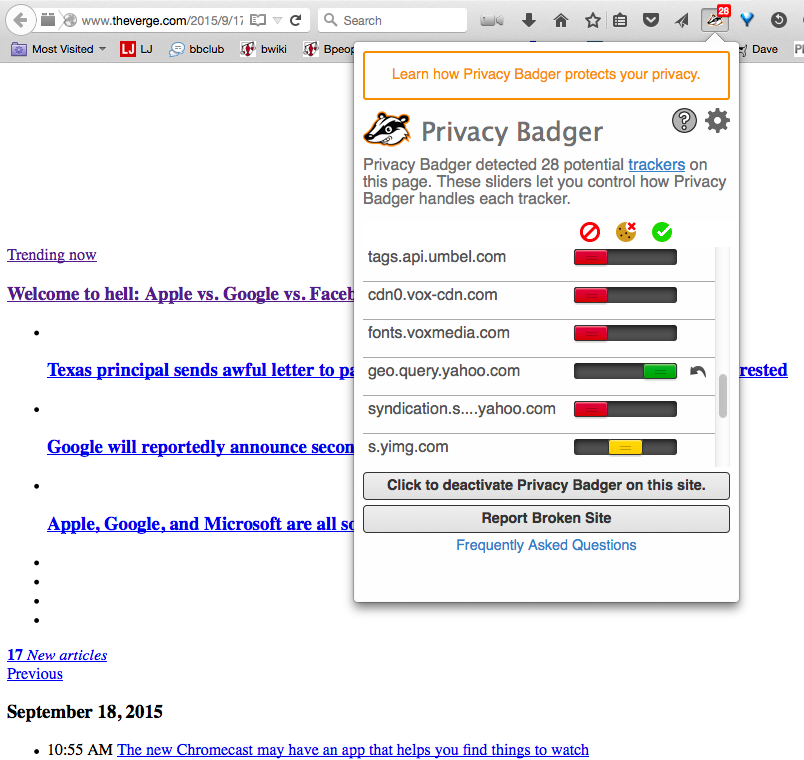

Ghostery provides some means for throttling some of those trackers. So do other tools, such as the EFF‘s Privacy Badger. Here’s what happens to the same page on Firefox when I activate Privacy Badger:

While Privacy Badger provides ways for me to valve the trackers sent to my browser by The Verge, it would take way more time than I have to figure out what trackers do what, and then play with the sliders until The Verge and I come to some kind of compromise.

Now here’s the main thing.

When we go to a Web page, we expect to see that page. That’s what the http protocol is for: a way to ask for a page. What we get from commercial sites like The Verge, however, is a bunch of other crap we didn’t ask for. Some of it is welcome, some of it isn’t and it’s damn hard to tell the difference.

The conversation we need to have is about what’s okay and what’s not okay. Ad and tracking blockers are giving us — the users (and in paying cases, the customers) — a crude and primitive way to say “Enough! That’s not okay!” And to start asserting some small degree of agency in a world where surveillance rules, and the individual has little control, other than to just walk away.

In Be the friction – Our Response to the New Lords of the Ring, Shoshana Zuboff gives us —

Zuboff’s three laws: First, that everything that can be automated will be automated. Second, that everything that can be informated will be informated. And most important to us now, the third law: In the absence of countervailing restrictions and sanctions, every digital application that can be used for surveillance and control will be used for surveillance and control, irrespective of its originating intention.

Ad and tracking blocking are countervailing restrictions and sanctions — a friction supplied by the marketplace.

Marketers and publishers can learn from what we’re saying with these tools. Or they can continue to misdirect our attention to what the Big Boys are doing while lecturing us about how we’re “killing the Web” or whatever.

The problem isn’t ad blocking. It’s surveillance. That’s what the real fight is about.

Meanwhile, it’s a shame to see the Chinese wall between editorial and advertising in publications turn into a trench. That’s what we see here.

(Parts of this post appeared in my Liveblog, on Fri, Sep 11, 2015. For much more, see my whole Adblock War Series.)

Leave a Reply