This is about visiting my great-great grandfather, Thomas Trainor, dead since 1876 and reposing in Calvary Cemetery in Queens, New York. Thomas and a friend bought the Trainor family plot, two graves wide, in 1852. It now lies roughly in the center of what’s called “Old Calvary,” the oldest section of the largest cemetery in the country. More than three people are buried there.

This is about visiting my great-great grandfather, Thomas Trainor, dead since 1876 and reposing in Calvary Cemetery in Queens, New York. Thomas and a friend bought the Trainor family plot, two graves wide, in 1852. It now lies roughly in the center of what’s called “Old Calvary,” the oldest section of the largest cemetery in the country. More than three people are buried there.

Calvary is familiar as the vast forest of monuments and headstones flanking the intersection of the Brooklyn Queens Expressway (I-278) and the Long Island (I-495) Expressway. Also as the place where the Godfather got planted in the movie.

Thomas was himself one of seven children. His parents were Thomas (or John) and Hanna (née Hockey) Trainor, said to be of Letterkenny, County Donegal, Ireland. He was born in 1804 and sailed to Boston at the height of the 1819 typhus epidemic at age 15, accompanied by his uncle, also a Trainor. By one account the uncle died soon after arriving, but by another he lived long enough to marry and widow the old aunt Thomas buried first in the family plot.

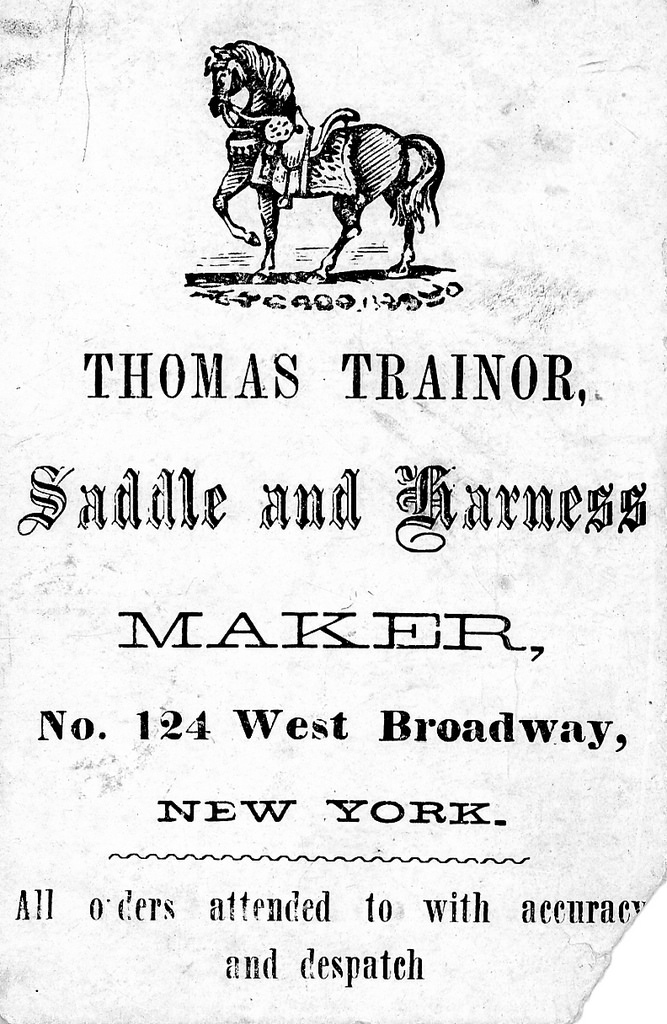

There is a gap in the record between the time Thomas arrived as a teen and when he came to own land in New York (around Poughkeepsie), meet Mary Ann McLaughlin, and established the saddle and carriage-building business described on his business card above. The family home, we know, was at 228 East 122nd Street in Harlem, at a time when most of the city’s roads were still dirt. (Here’s the Streetview today.) His business, at 124 West Broadway, was at the corner of Duane on the east edge of what is now Tribeca. Mary Ann did the carriage interiors when she not also producing children. Family lore also has it that Thomas trained first as a servant indentured to Mary Ann’s dad. Also that this is false.

What I found at Calgary, after a long search (having been given bad instructions at first by an otherwise helpful guy at the cemetery office), was this headstone:

Clearly this is the Trainor plot: Section 1W, Range 6, Plot U. (Nice of some stones to have that engraving. Most don’t.) And I know Margaret Mayer was Thomas’s youngest daughter, known to us kids growing up as Grandma Searls’ “Aunt Mag.” Here she is:

Clearly this is the Trainor plot: Section 1W, Range 6, Plot U. (Nice of some stones to have that engraving. Most don’t.) And I know Margaret Mayer was Thomas’s youngest daughter, known to us kids growing up as Grandma Searls’ “Aunt Mag.” Here she is:

Grandma Searls was the third of five children, all daughters, of Henry Roman Englert and Catherine “Kitty” Trainor, the fourth of Thomas and Mary Ann’s seven kids. Henry was the head of New York’s Steel and Copperplate Engravers Union, and the family home was in the South Bronx at 742 East 142nd Street. When Kitty died at age 39, Aunt Mag became a second mom to Kitty’s four surviving daughters.

Grandma Searls was the third of five children, all daughters, of Henry Roman Englert and Catherine “Kitty” Trainor, the fourth of Thomas and Mary Ann’s seven kids. Henry was the head of New York’s Steel and Copperplate Engravers Union, and the family home was in the South Bronx at 742 East 142nd Street. When Kitty died at age 39, Aunt Mag became a second mom to Kitty’s four surviving daughters.

But who was Grace F. Adams? And why are there no dates, or names other than those two, neither of whom died with the Trainor surname?

Some answers came when I got home and looked through the typed records of Catherine Burns, daughter of Florence, Grandma Searls’ younger sister. These were scanned by Catherine’s son Martin (my second cousin), and shared along with many other pictures I’ve put up on the Web.

There I discovered that Grace Adams is the granddaughter of Aunt Mag, who was born in 1855, two years before her mother died, and lived for another 89 years. She married Joseph Mayer in 1881, the year before Grandma Searls (née Ethel F. Englert) was born. (Joseph, who died in 1927, is buried elsewhere at Calgary.) Mag and Joseph’s daughter Frances, born in 1888, married George Shannon. (After Geroge died in 1923, she married John Heslin, who also predeceased her without fathering more children.) Frances and George produced Gertrude Doris Shannon and Grace Shannon. Gertrude, born in 1918, married Thomas Doonan in 1937, and had four kids: Thomas Jr., Margaret, Rosemary and John. They and their descendants are third, fourth and fifth cousins of mine.

But the connection to the headstone is Grace Shannon, born in 1919. She married an Adams (first name unknown), and produced two daughters, Candice and Denise, born respectively in 1953 and 1957. They are third cousins of mine (sharing great-great grandparents). Candice married Joseph Flasch and produced two known children, Joseph and Shannon Marie.

So Grace Shannon is the Grace F. Adams on the headstone. Since died in 1966 at just 45 years old, and the headstone (or monument, in the parlance of the cemetery business) is clearly of relatively recent vintage, I am guessing it was was placed by one or both of Grace F. Adams’ daughters. I am also guessing that they knew this was a Trainor plot, with lots of Trainors in it, but didn’t want to go into the details, especially since some of them are hazy. Hence the names of the two ancestors they knew and cared most about, under the Trainor heading.

I’m saying all this in hope that one or more of them will find this post and fill us in.

What the only headstone at the Trainor plot understates is that bodies of nine family members (and perhaps one other) are stacked in just two graves:

Their order of burial also recalls a series of tragedies. First in the ground was an elderly aunt, apparently the widow of the uncle who came over with Thomas from Ireland. Next was Thomas’s wife, Mary Ann, age 36. Then went three of their seven children: 1 year old Thomas Jr., 16 year old Charles, and then 31 year old Hannah Crowley. Not included is an infant daughter, Ella, buried elsewhere.

Their order of burial also recalls a series of tragedies. First in the ground was an elderly aunt, apparently the widow of the uncle who came over with Thomas from Ireland. Next was Thomas’s wife, Mary Ann, age 36. Then went three of their seven children: 1 year old Thomas Jr., 16 year old Charles, and then 31 year old Hannah Crowley. Not included is an infant daughter, Ella, buried elsewhere.

The story of Charles is family legend, but accounts differ. They agree that he ran away at 16, twice, to fight in the Civil War. One report says he was killed carrying a flag. Another says he was wounded and died in an army hospital. By that story he was visited by his father after a search made long and difficult by Charles’s decision to register under an assumed name that only he and the Union Army knew. When Thomas found Charles, the boy was almost unrecognizable behind a full red beard. According to that story (the one in which Charles wasn’t killed in battle), the doctors promised Thomas that his boy would be home by Christmas. There seems to be agreement that Charles died on Thanksgiving Day, and arrived home in a box. Grandma Searls (a niece of Charles through his sister Catherine) said Charles arrived home on Christmas Day.

All family accounts agree that Charles was planted in the Trainor plot at Calvary. The Cemetery records do not agree. Instead it lists Hannah Kennedy as an occupant of the Trainor plot. According to that listing, she was Charles’ age when she died the same year. So there are three possibilities here. The first is that Hannah was a family acquaintance who just happened to die at the same age as Charles and in the same year. The second is that the cemetery made a mistake in recording the burial. The third is that both are buried there, and only Hannah’s burial is recorded. I favor the second possibility because it’s the most plausible. Today we’d call it a data entry error.

When I asked the guy at the Calvary office how burying stacked bodies in a single grave worked in an age when they didn’t use vaults, he said something like, “They just dig down until they find the top of the coffin below. Or they stop when they find remains or what they suspect are remains, and set the next coffin on top.”

What they find, if a coffin is absent, would depend on the soil. In the red-dirt South, where there is a lot of acid in the soil, I am told there tends to be nothing left after a few years but buttons and shoelace grommets. But in other soils, such as in France, where they relocated all the remains in all of Paris’s cemeteries into quarries under the city (now called the catacombs) from the late 1700s to mid 1800s, all the bones stay in perfect shape. (I visited there in ’10. Amazing place.)

When I was in Letterkenny a few years ago, I thought I would try to find some trace of the Trainors who stayed behind. Turns out Trainor is a fairly common name that roughly means laborer, or strong man, in the original Gaelic Thréinfhir. There are also many variants, including Armstrong. So I took my curiosity to the Parochial House across from St. Eunan’s Cathedral in Letterkenny, and was rebuked by one of the priests there. Didn’t I know the Irish Catholic Church was underground in the early 1800s, while all of Ireland was under England’s thumb and enduring one famine and plague after another? In other words, “Don’t bother askin’.”

He did at least point me to a graveyard near Old Town, across the River Swilly. It was in use two centuries ago, when Great-great Grandpa Thomas was growing up there, and might contain some Trainors or Hockeys, he said. When we went by, however, it was raining heavily, and there was a funeral underway — one of the first there in a long time, we were told by one of those attending. So we gave up.

For what it’s worth, I’ve looked a bit into Donegal genealogy records for evidence of Trainors, or Thréinfirs, and found nothing. But the Trainors may not have been from Letterkenny, or Donegal. I’ve heard variously that they were from County Monaghan, or Cork. A search here brings up 85,651 birth records for Thomas Trainor in Monaghan. Seems mighty high, but maybe I’m doing it wrong.

Last year I took my wife on what she called “a really bad idea for a date” (as was the Letterkenny side trip): visiting the graves of other relatives on Grandma’s father’s side:

- Christian Englert (my great-great grandfather, same generation as Thomas Trainor), his wife Jacobina (née Rung) Englert, and five others in the next generation, including four who died young (aged 33, 29, 1 and 10 months). Only three of those are marked on the headstone. Here they are in roughly 1869.

- Christian’s son, Henry Roman Englert, his wife Kitty Trainor (one of the sibs not buried in Calvary), Henry’s second wife (Teresa Antonelli), and three from the next generation, all of whom died young and are stacked into three graves in one plot below a small wedge-shaped headstone that identifies Henry alone.

I couldn’t find a third grave site, possibly not marked, containing Henry’s brother Andrew and (stacked atop him) a daughter or niece, Annie Englert. This one may not be marked.

Martin tells me that the four Englert sisters and others of their generation would often visit the graves of their mother and siblings, even before their father, Henry, died in 1943. I am sure that none of those graves would have been marked. It also seems strange to me that they (or somebody) only marked Henry’s after he died, without mention of the five others below.

Anyway, I’ve shared documents and pictures of Trainors here, Englerts here, and Dwyers (Martin’s family) here.

All of this inquiry also has me thinking about what cemeteries are for. Clearly the idea of organizing the dead under plaques, stones and monuments is to honor and host those who miss them, or who wish at least to respect them, as I did for all those piled-up Trainors last Saturday.

I suppose the original purpose of burial was to hold the stink down, or to recycle nutrients where the process can’t be seen. (Beats watching vultures and less grand creatures do the job.) Whatever it was, it seems kind of wasteful and obsolete at this point.

Over dinner a few years ago, Kevin Kelly told me that nobody we know, including ourselves, will be remembered in a thousand years — or even a hundred or two. Each of us at most is an Ozymandias, or a Shelley, who wrote his famous sonnet before drowning at 29. Here it is:

I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said: “Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed:

And on the pedestal these words appear:

‘My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!’

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

I was the traveler on Saturday. New York was, for that day, my antique land. Around the Trainor graves Calvary seemed boundless, though hardly bare, covered by ranks of headstones, statues and thick granite houses for the above-ground dead: lifeless things, all. Lone it also seemed, since I saw not one other pedestrian (and just one other car) during the hours I wandered there, on a day that could hardly have been more sunny, mild and welcoming.

All of it seemed to certify, as does the hand of Ozymandias’ sculptor, the full depth of departure: that all will be forgotten, and only stone pedestals for absent memories will remain.

The job of the living, I believe, is to leave the world better than we found it. That’s all. Whether we do that job or not, we are still obliged to leave. That’s a lesson I learned from my mother, after she died:

So many times I think about something I’d love to share with Mom or Pop, then remember they’re gone. Often I hear Mom’s voice: firm, instructive and loving as ever. Give to the living, she says. That’s what love is for. Her lesson: Death makes us give love to the living. She was a teacher. Still is.

And so are they all, even if now we know next to nothing about them.

Leave a Reply