The world of distance

Fort Lee is the New Jersey town where my father grew up. It’s at the west end of the George Washington Bridge, which he also helped build. At the other end is Manhattan.

Even though Fort Lee and Manhattan are only a mile apart, it has always been a toll call between the two over a landline. Even today. (Here, look it up.) That’s why, when I was growing up not far away, with the Manhattan skyline looming across the Hudson, we almost never called over there. It was “long distance,” and that cost money.

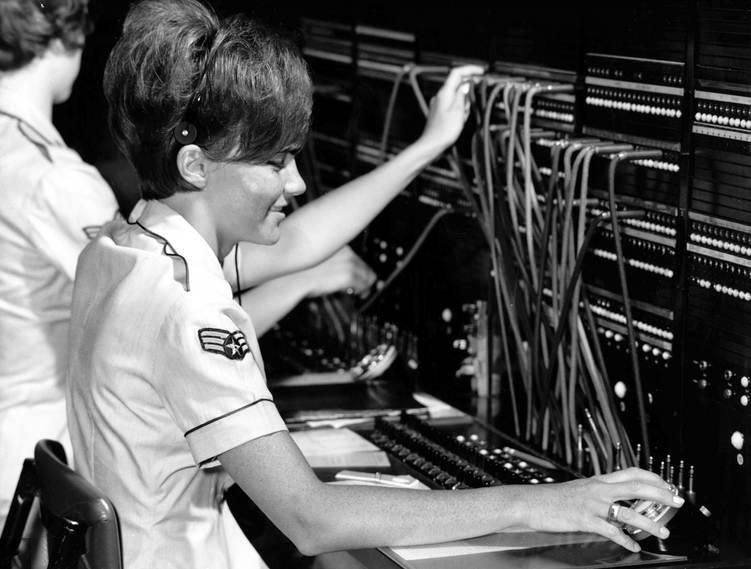

There were no area codes back then, so if you wanted to call long distance, you dialed 0 (“Oh”) for an operator. She (it was always a she) would then call the number you wanted and patch it through, often by plugging a cable between two holes in a “switchboard.”

Toll-free calls could be made only to a few dozen local exchanges listed in the front of your phone book. Calls to distant states were even more expensive, and tended to sound awful. Calls outside the country required an “overseas operator,” were barely audible, and cost more than a brake job.

That’s why, to communicate with our distant friends and relatives, we sent letters. From 1932 to 1958, regular (“first class”) letters required a 3¢ stamp. This booked passage for the letter to anywhere in the country, though speeds varied with distance, since letters traveled most of the way in canvas bags on trains that shuttled between sorting centers. So a letter from New Jersey to North Carolina took three or four days, while one to California took a week or more. If you wanted to make letters travel faster, you bought “air mail” stamps and put them on special envelopes trimmed with diagonal red and blue stripes. Those were twice the price of first class stamps.

The high cost of distance for telephony and mail made sense. Farther was harder. We knew this in our bodies, in our vehicles, and through our radios and TVs. There were limits to how far or fast we could run, or yell, or throw a ball. Driving any distance took a sum of time. Even if you drove fast, farther took longer. Signals from radio stations faded as you drove out of town, or out of state. Even the biggest stations — the ones on “clear” channels, like WSM from Nashville, KFI from Los Angeles and WBZ from Boston — would travel hundreds of miles by bouncing off the sky at night. But the quality of those signals declined over distance, and all were gone when the sun came up. Good TV required antennas on roofs. The biggest and highest antennas worked best, but it was rare to get good signals from more than a few dozen miles away.

All our senses of distance are rooted in our experience of space and time in the physical world. So, even though telephony, shipping and broadcasting were modern graces most of our ancestors could hardly imagine, old rules still applied. We knew in our bones that costs ought to vary with the labors and resources required. Calls requiring operators should cost more than ones that didn’t. Heavier packages should cost more to ship. Bigger signals should require bigger transmitters that suck more watts off the grid.

A world without distance

Everything I just talked about — telephony, mail, radio and TV — are in the midst of being undermined by the Internet, subsumed by it, or both. If we want to talk about how, we’ll have nothing but arguments and explanations. So let’s go instead to the main effect: distance goes away.

On the Net you can have a live voice conversation with anybody anywhere, at no cost or close enough. There is no “long distance.”

On the Net you can exchange email with anybody anywhere, instantly. No postage required.

On the Net anybody can broadcast to the whole world. You don’t need to be a “station” to do it. There is no “range” or “coverage.” You don’t need antennas, beyond the unseen circuits in wireless devices.

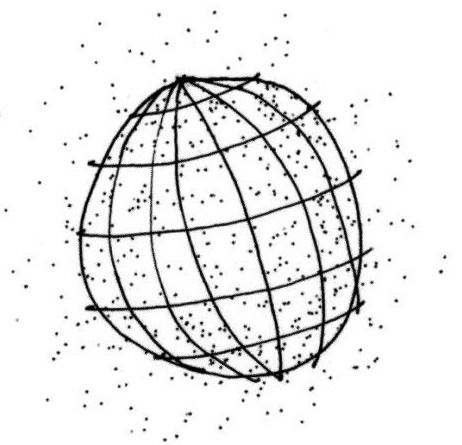

I’ve been wondering for a long time about how we ought to conceive the non-thing over which this all happens, and so far I have found no improvements on what I got from Craig Burton in an interview published in the August 2000 issue of Linux Journal:

Doc: How do you conceive the Net? What’s its conceptual architecture?

Craig: I see the Net as a world we might see as a bubble. A sphere. It’s growing larger and larger, and yet inside, every point in that sphere is visible to every other one. That’s the architecture of a sphere. Nothing stands between any two points. That’s its virtue: it’s empty in the middle. The distance between any two points is functionally zero, and not just because they can see each other, but because nothing interferes with operation between any two points. There’s a word I like for what’s going on here: terraform. It’s the verb for creating a world. That’s what we’re making here: a new world.

A world with no distance. A Giant Zero.

Of course there are many forms of actual distance at the technical and economic levels: latencies, bandwidth limits, service fees, censors. But our experience is above those levels, where we interact with other people and things. And the main experience there is of absent distance.

We never had that experience before the Internet showed up in its current form, about twenty years ago. By now we have come to depend on absent distance, in countless ways that are becoming more numerous by the minute. The Giant Zero is a genie that is not going back in the old bottle, and also won’t stop granting wishes.

Not all wishes the Giant Zero grants are good ones. Some are very bad. What matters is that we need to make the most of the good ones and the least of the bad. And we can’t do either until we understand this new world, and start making the best of it on its own terms.

The main problem is that we don’t have those terms yet. Worse, our rhetorical toolbox is almost entirely native to the physical world and misleading in the virtual one. Let me explain.

Talking distance

Distance is embedded in everything we talk about, and how we do the talking. For instance, take prepositions: locators in time and space. There are only a few dozen of them in the English language. (Check ‘em out.) Try to get along without over, under, around, through, beside, along, within, on, off, between, inside, outside, up, down, without, toward, into or near. We can’t. Yet here on the Giant Zero, everything is either present or not, here or not-here.

Sure, we are often aware of where sites are in the physical world, or where they appear to be. But where they are, physically, mostly doesn’t matter. In the twenty years I’ve worked for Linux Journal, its Web server has been in Seattle, Amsterdam, somewhere in Costa Rica and various places in Texas. My own home server started at my house in the Bay Area, and then moved to various Rackspace racks in San Antonio, Vienna (Virginia) and Dallas.

While it is possible for governments, or providers of various services, to look at the IP address you appear to be using and either let you in or keep you out, doing so violates the spirit of the Net’s base protocols, which made a point in the first place of not caring to exclude anybody or anything. Whether or not that was what its creators had in mind, the effect was to subordinate the parochial interests (and businesses) of all the networks that agreed to participate in the Internet and pass data between end points.

The result was, and remains, a World of Ends that cannot be fully understood in terms of anything else, even though we can’t help doing that anyway. Like the universe, the Internet has no other examples.

This is a problem, because all our speech is metaphorical by design, meaning we are always speaking and thinking in terms of something else. According to cognitive linguistics, every “something else” is a frame. And all frames are unconscious nearly all the time, meaning we are utterly unaware of using them.

For example, time is not money, but it is like money, so we speak about time in terms of money. That’s why we “save,” “waste,” “spend,” “lose,” “throw away” and “invest” time. Another example is life. When we say birth is “arrival,” death is “departure,” careers are “paths” and choices are “crossroads,” we are thinking and speaking about life in terms of travel. In fact it is nearly impossible to avoid raiding the vocabularies of money and travel when talking about time and life. And doing it all unconsciously.

These unconscious frames are formed by our experience as creatures in the physical world. You know why we say happy is “up” and sad is “down”? Or why we compare knowledge with “light” and ignorance with “dark”? It’s because we are daytime animals that walk upright. If bats could talk, they would say good is dark and bad is light.

Metaphorical frames are not only unconscious, but complicated and often mixed. In Metaphors We Live By, George Lakoff and Mark Johnson point out that ideas are framed in all the following ways: fashion (“old hat,” “in style,” “in vogue”), money (“wealth,” “two cents worth, “treasure trove”), resources (“mined a vein,” “pool,” “ran out of”), products (“produced,” “turning out,” “generated”), plants (“came to fruition,” “in flower,” “budding”), and people (“gave birth to,” “brainchild,” “died off”).

Yet none of those frames is as essential to ideas as what Michael Reddy calls the conduit metaphor. When we say we need to “get an idea across,” or “that sentence carries little meaning,” we are saying that ideas are objects, expressions are containers, and communications is sending.

So let’s look at the metaphorical frames we use, so far, to make sense of the Internet.

When we call the Internet a “medium” through which “content” can “delivered” via “packets” we “uploaded,” “downloaded” between “producers” and “consumers” through “pipes,” we are using a transport frame.

When we talk about “sites” with “domains” and “locations” that we “architect,” “design,” “build” and “construct” for “visitors” and “traffic” in “world” or a “space: with an “environment,” we are using a real estate frame.

When we talk about “pages” and other “documents” that we “write,” “author,” “edit,” “put up,” “post” and “syndicate,” we are using a publishing frame.

When we talk about “performing” for an “audience” that has an “experience: in a “venue,” we are using a theater frame.

And when we talk about “writing a script for delivering a better experience on a site,” we are using all four frames at the same time.

Yet none can make full sense of the Giant Zero. All of them mislead us into thinking the Giant Zero is other than what it is: a place without distance, and lots of challenges and opportunities that arise from its lack of distance.

Terraforming The Giant Zero

William Gibson famously said “the future is already here, it’s just not evenly distributed.” Since The Giant Zero has only been around for a couple decades so far, we still have a lot of terraforming to do. Most of it, I’d say.

So here is a punch list of terraforming jobs, some of which (I suspect) can’t be done in the physical world we know almost too well.

Cooperation. Getting to know and understand other people over distances was has always been hard. But on The Giant Zero we don’t have distance as an excuse for doing nothing, or for not getting to know and work together with others. How can we use The Giant Zero’s instant proximity to overcome (and take advantage) of our differences, and stop hating The Other, whoever they may be?

Privacy. The Giant Zero doesn’t come with privacy. Nor does the physical world. But distance alone gives some measure of privacy in the physical world. We also invented clothing and shelter as privacy technologies thousands of years ago, and we have well developed manners for respecting personal boundaries. On The Giant Zero we barely have any of that, which shouldn’t be surprising, because we haven’t had much time to develop them yet. In the absence of clothing, shelter and boundaries, it’s ridiculously easy for anyone or anything to spy our browsings and emailings. (See Privacy is an Inside Job for more on that, and what we can do about it.)

Personal agency. The original meaning of agency (derived from the Latin word agere, meaning “to do”), is the power to act with full effect in the world. We lost a lot of that when Industry won the Industrial Revolution. We still lose a little bit every time we click “accept” to one-sided terms the other party can change and we can’t. We also lose power every time we acquiesce to marketers who call us “assets” they “target,” “capture,” “acquire,” “manage,” “control” and “lock in” as if we were slaves or cattle. In The Giant Zero, however, we can come to the market as equals, in full control of our data and able to bring far more intelligence to the market’s table than companies can ever get through data gathered by surveillance and fed into guesswork mills that: a) stupidly assume that we are always buying something and b) still guess wrong at rates that round to 100% of the time. All we need to do is prove that free customers are more valuable than captive ones — to the whole economy. Which we can if we build our own tools for both independence and engagement. (Which we are.)

Politics and governance. Elections in democratic countries have always been about sports: the horse race, the boxing ring, the knockout punch. The Internet changes all that in many ways we already know and more we don’t. But what about governance? What about direct connections between citizens and the systems that serve them? The Giant Zero exists in all local, state, national and global government contexts, waiting to be discovered and used. And how should we start thinking about laws addressing an entirely new world we’ve hardly built and are years away from understanding fully (if we ever will)? In a new world being terraformed constantly, we risk protecting yesterday from last Thursday with laws and regulations that will last for generations — especially when we might find a technical solution next Tuesday to last Thursday‘s problems.

Economics. What does The Giant Zero in our midst mean for money, accounting and everything in Econ 101, 102 and beyond? Today we already have Bitcoin and its distributed ledger, the block chain. Both are only a few years old, and already huge bets are being made on their successes and failures. International monetary systems, credit payment and settlement mechanisms are also challenged by digital systems of many kinds that are zero-based in several different meanings of the expression. How do we create economies that are both native to The Giant Zero and respectful of the physical world it cohabits?

The physical world. We live in an epoch that geologists are starting to call the Anthropocene, because it differs from all that preceded it in one significant way: it is altered countless ways by human activity. At the very least, it is beyond dispute that our species is, from the perspective of the planet itself, a pestilence. We raid it of irreplaceable substances deposited by life forms (e.g. banded iron) and asteroid impacts (gold, silver, uranium and other heavy metals) billions of years ago, and of the irreplaceable combustible remains of plants and animals cooked in the ground for dozens to hundreds of millions of years. We fill the planet’s air and seas with durable and harmful wastes. We wipe out species beyond counting, with impunity. We have littered space with hundreds of thousands of pieces of orbiting crap flying at speeds ten times faster than bullets. The Giant Zero can’t reverse the damage we’ve caused, or reduce our ravenous appetites for more of everything our species selfishly calls a “resource.” But it puts us in the best possible position to understand and deal with the problems we’re causing.

The “Internet of Things” (aka IoT) is a huge topic, even though most of the things being talked about operate in closed and proprietary silos that may not even use the Internet. But what if they actually were all to become native to The Giant Zero? What if every thing — whether or not it has smarts inside — could be on the Net, at zero distance from every other thing, and capable of interacting in fully useful ways for their owners, rather than the way they’re being talked about now: as suction cups on corporate and government tentacles?

Inequality. What better than The Giant Zero’s absent distance to reduce the distance between rich and poor — and to do so in ways not limited to the familiar ones we argue about in the physical world?

The unconnected. How do we migrate the last 1.5 billion of us from Earth to The Giant Zero?

A question

I could go on, but I’d rather put another question to those of you who have made it to the end of this post: Should The Giant Zero be a book? I’m convinced of the need for it and have a pile of material already. Studying all this has also been my focus for a decade as a fellow with the Center for Information Technology and Society at UCSB. But I still have a long way to go.

If pressing on is a good idea, I could use some help thinking it through and pulling materials together. If you’re interested, let me know. No long distance charges apply.

This piece is copied over from this one in Medium, and is my first experiment in publishing first there and second here. Both are expanded and updated from a piece published at publius.cc on May 16, 2008. The drawing of the Internet is by Hugh McLeod. Other images are from Wikimedia Commons.

Leave a Reply