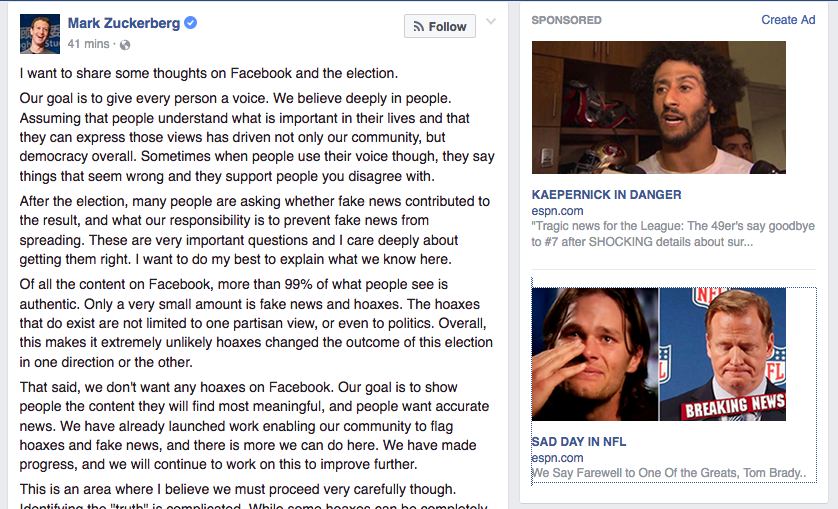

Nearly all the ads I see on Facebook are fake news items like these two, next to Mark Zuckerberg’s latest post, which is, ironically, about fake news:

Besides being false and misleading clickbait, these ads are not from espn.com. They’re from http://espn.com-magazines.online. They are also bait for a topic switch, since they’re actually about a diet supplement I won’t flatter by naming. So they’re two kinds of fraud at once: outright lies from a forged source.

Besides being false and misleading clickbait, these ads are not from espn.com. They’re from http://espn.com-magazines.online. They are also bait for a topic switch, since they’re actually about a diet supplement I won’t flatter by naming. So they’re two kinds of fraud at once: outright lies from a forged source.

It can’t be that hard for Facebook not to run this kind of obviously dishonest and misleading advertising, especially since this story itself is old news. (See here.) Why hasn’t it been stopped?

I’m guessing the answer is a technical one: that Facebook’s advertising system is too easy a hack for dishonest advertisers to resist, and too hard to change.

Either that, or the money they make from ad fraud more than offsets the cost of egg on their CEO’s face.

Save

Leave a Reply