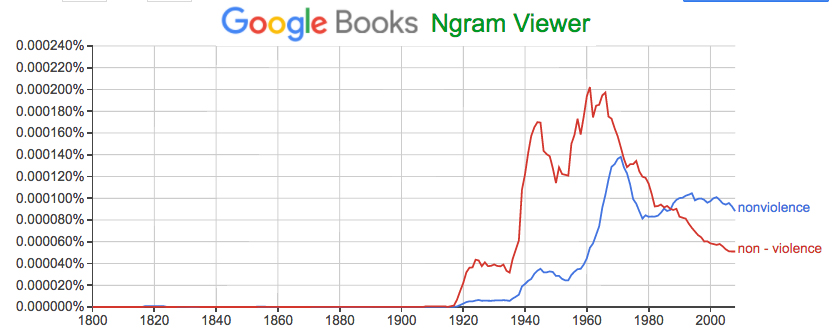

Two graphs tell some of the story.

First is how often “nonviolence” and “non-violence” appeared in books until 2008, when Google quit keeping track:

Second is search trends for “nonviolence” and “non-violence” since 2004, which is when Google started keeping track of trends:

Clearly nonviolence wasn’t a thing at all until 1918, which is when Mohandas Gandhi started bringing it up. It became a big thing again in the 1960s, thanks to Martin Luther King Jr. and the civil rights movement he led during the Vietnam war.

Then, at the close of the 60s, it trailed off. Not that it ever went away, but it clearly retreated.

Why?

Here’s the part of the story that seems clearest to me, and to the late Bill Hicks:

Spake Bill, “We kill those people.”

I was only a year old when Gandhi was shot, so I don’t remember that one; but I was involved in both the civil rights and antiwar movements in North Carolina when Martin Luther King was gunned down in June 1968, and Bobby Kennedy a few days later.

I cannot overstate the senses of grief, despair and hopelessness that followed those two assassinations. (And of Malcolm X three years earlier. And again when Nixon got elected a few months later in ’68.)

Two things were clear to me at the time: that violence won, and that the civil rights and antiwar movements were set back decades by those events.

Those observations have been borne out in the half-century since. Yes, there is still peaceful resistance, as there has been at various times and ways, going back at least as far as ahimsa in the Jain, Buddhist and Hindu faiths.

But where is it now? Look for nonviolence in Google News and you’ll find some nice stuff, but nothing that looks like a movement to counterbalance the violence in the world, or the hostile prejudices that fuel it.

Racism and appetites for violent conflict today are hardly less embedded than they ever were, and are now emboldened within the echo chambers of tribalisms old and new—the latter thanks to online media, some of which seem purpose-built to gather, isolate and amplify hostilities. (Bonus link: Down the Breitbart Hole, in last Sunday’s NY Times.)

I can hear the arguments: “look at all the examples of peaceful marches” and so on. But nonviolence itself, as a virtue and a strategy, is back-burnered at best, and lacks a single exemplar or advocate on the scale of a Gandhi or a King.

Hell, maybe I’m wrong about it. If I am, tell me how. My mind is hardly made up on this.

Leave a Reply