Where does public radio rock—or even rule? And why?

To start answering those questions, I looked through Nielsen‘s radio station ratings, which are on the Radio Online site. I dug down through all the surveyed markets, from #1 (New York NY) through #269 (Las Cruces-Deming NM), and pulled out the top 31 markets for public radio (where the share was over 6.0 — all numbers are % of all listening within a geographic market). Here ya go:

- Santa Barbara CA (where KCLU is #1), 23.4

- Burlington VT (where WVPS is #1), 17.2

- Montpelier-Barre-Waterbury VT (where WVPS is #1), 17.0

- Asheville NC (where WCQS/WYQS is #2 with 11.8 and WNCW is #3 with 4.0)

- Ann Arbor, MI (where WUOM is #1 and WEMU is tied at #2), 15.1

- Cape Cod MA (where WCAI is #2), 14.6

- Portland OR (where KOPB is tied at #2), 12.6

- Denver-Boulder CO (where KCFR is #1), 12.3

- Austin TX (where KUT is #1), 11.3

- Eugene-Springfield (where KLCC is #2), 11.3

- Washington, DC (where WAMU is #2 and sometimes #1), 11.3

- San Francisco CA (where KQED has been #1 through the all the posted surveys), 11.0

- Seattle-Takoma WA (where KUOW has been #1 through the all the posted surveys), 10.9

- Raleigh-Durham NC (where WUNC is #4), 10.6

- Portland ME (where WMEA is #1), 10.5

- San Jose CA (where KQED is #3), 9.9

- Concord (Lakes Regions) NH (where WEVO is #1) 9.3

- Boston MA (where WBUR is #7), 8.9

- San Luis Obispo CA (where KCBX is #2), 8.9

- Columbia MO (where KBIA is #4), 8.6

- Tallahassee FL (where WFSU is #3), 8.6

- Washington DC (where WAMU is #2 and sometimes #1), 8.6

- Sarasota-Bradenton FL (where WUSF is #2 and WSMR is #3) 8.2

- Monterey CA (where KAZU was #2), 7.7

- Gainesville-Ocala FL (where WUFT is #4), 7.3

- New Haven CT (where WSHU is #6), 7.3

- Lafayette IN (where WBAA-AM is #1 and WBAA-FM is #3), 7.0

- Traverse City-Petoskey-Cadillac MI (where WICA is #7), 6.7

- Hartford-New Britain CT (where WNPR is #9), 6.5

- Oxnard-Ventura CA (where KCLU is #4), 6.3

- Grand Junction CO (where KPRN is #5), 6.1

- San Diego, CA (where KPBS is a near-constant #1). It is 6.3 in December 2019, as I’m adding it, after a reader spotted my oversight in leaving San Diego out of this list.

(Note: Totals above are of noncommercial stations with typical public radio formats: NPR-type news and programming, plus classical, jazz and alternative music. I didn’t include noncommercial religious stations†).

Of course I’m pleased to find my town, Santa Barbara, on top. Here’s how Nielsen breaks out station ratings within that 23.4 share number.

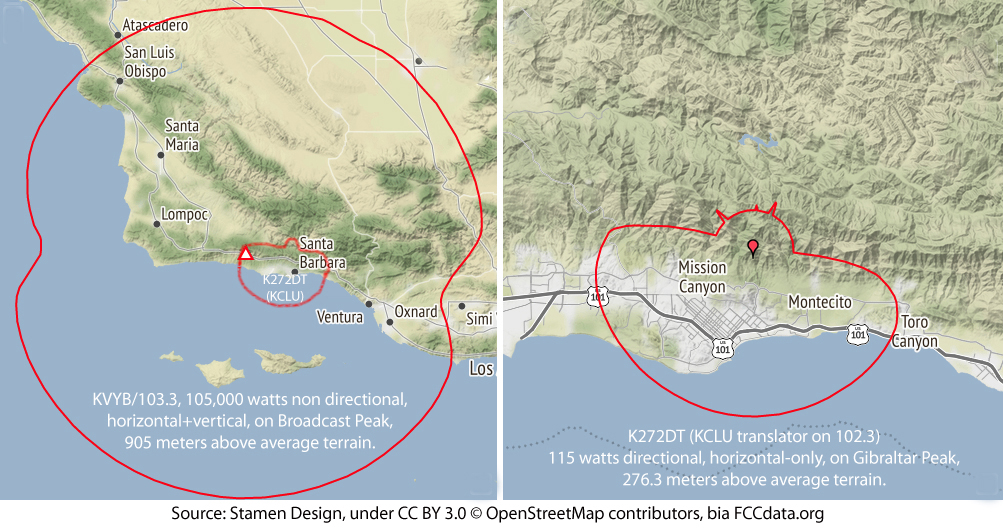

- KCLU-FM 7.8. This is KCLU’s 110-watt translator on 102.3, not the home station on 88.3 in Thousand Oaks, which barely gets into town. (Note that this signal is directional, meaning weaker in all directions other than straight into town. This number is remarkable for a translator. For more on that, see the map below.)

- KCLU-AM 2.6. This signal has the same audio as KCLU-FM, so the two together are 9.4, which makes KCLU #1, edging KTYD, the landmark local rock station, which gets a 9.2.

- KUSC 5.2. Though reported as KUSC, this is actually KDB/93.7, which carries the audio of KUSC from Los Angeles.

- KCRW 3.9. This is surely KDRW, which mostly identifies as KCRW, since most of the time KDRW carries the audio of KCRW, from Santa Monica/Los Angeles.

- KDRW 1.3. This is a case of one station reported two different ways. Together they total 5.2.

- KCBX 1.3. This is KSBX, a 50-watt repeater of KCBX from San Luis Obispo, which has no signal at all in town (being shadowed by the 4000-foot Santa Ynez Mountain range). Also, though reported as KCBX, the listening might be to KPBS in San Diego, a public radio station on the same channel that pounds into Santa Barbara much of the time.

- KPCC 1.3. This is the 10-watt translator of KPCC from Pasadena/Los Angeles. KPCC’s home signal doesn’t reach here.

So: why Santa Barbara? Here’s what I think:

- Demographics. Santa Barbara is an upscale university town with a bonus population of active older folks who are intellectually and culturally engaged. NPR, for example, tends to do well with that combination of crowds.

- Lots of signals. There is now a surfeit of public radio signals in Santa Barbara.The list above is unusually large for a town this size, and doesn’t include stations that serve the market but didn’t make the ratings, such as KPFK (Los Angeles most powerful FM station, which also has a local 10-watt translator) and UCSB’s college radio station, KZSB).

- Geographic isolation. Santa Barbara is far enough from big market signals to make them weak or absent. (Some do get in, and even show a bit in the ratings.) I think the same kind of thing can also be said for many of the other smaller markets where public radio does well.

- News coverage. There are three two steady sources of local news in Santa Barbara: local/regional TV (notably KEYT/3), local print (both online and off), and public radio—especially KCLU, which has won three Murrow Awards and six AP awards in the last two years. Of its news director, Lance Orozco, KCLU says, “Lance has won more than 200 journalism awards for KCLU, including more than 90 Golden Mikes, 20-plus regional Edward R. Murrow awards, a national Edward R. Murrow Award (an honor which came to David Letterman’s attention on “The Late Show.”), and a national Society Of Professional Journalists Award He has been AP’s small market reporter of the year in the western U.S. nine times.”

- Disasters. Santa Barbara has a long and almost steady record of wildfires, the largest of which was the Thomas Fire in December 2017, followed by massive debris flows during a storm in January 2018. Public Radio and other local media became indispensable during that time. I suspect it has stayed that way in a time when national news has become more partisan and less anchored to facts “on the ground,” as they say.

Montecito debris flow, January 2018. From KEYT/3.

Montecito debris flow, January 2018. From KEYT/3.

I also think some other factors are in play here—factors with meaning that go far beyond Santa Barbara:

- Local and regional news lives on in public radio while it has been dying off on the commercial side. Old-fashioned “full service” local radio has been in retreat across the country. Stations categorized as “news” or “news/talk” in the ratings (and within the industry) are now mostly conduits for political talk. True full-time pure news stations thrive only in the largest markets, where the news operations can afford the reporters. Specifically those are New York (WCBS and WINS), Philadelphia (KYW), Washington (WTOP), Chicago (WBBM), Los Angeles (KNX) and San Francisco (KCBS). That’s it. (In fact one of L.A.’s two news stations, KFWB, dropped the format in 2014.)

- Public radio may be the only part of shared culture, other than sports, where the media center still holds. This too owes to being anchored in local culture, and reporting on local news, which by necessity tends to be less partisan than national news has become.

- Listener abandonment of over-the-air radio, especially for music. Music and talk listening has been shifting for years from over-the-air to streaming services, satellite radio and podcasts, leaving public radio with a higher percentage of listening to over-the-air broadcasts.

- Embrasure of streaming, satellite radio, podcasting, smart speakers and other new technologies. Public broadcasting has long been ahead of the technical curve, and in the last decade has done an excellent job of maximizing what can still be done with legacy over-the-air broadcasting (for example, buying up signals with low market value—as KCLU did with its AM in Santa Barbara—and planting translators and repeater stations all over the place), while also pioneering on the digital front. Noncommercial and religious broadcasters have both been highly resourceful and ahead of the curve on The Great Digital Shift.

- Turning localism into a big competitive advantage. Something that has long been a weakness of public radio, especially NPR—its fealty to stations, refusing to subordinate the network to those—is turning into an advantage, as local programming matters more and more. Even in the midst of The Great Digital Shift, we remain physical beings who live in the natural world, vote in local elections, drive in local traffic, care about local teams, deal with local emergencies, and depend on each other’s helping hands when and where it matters most. Public radio is especially compatible with all that. (Note: this was the subject of my TEDx talk in Santa Barbara last September.)

- Re-defining regionalities. What makes a region a region, or a market a market? I think public radio is playing a role in defining both, especially as commercially-supported news becomes more partisan and less well funded by advertising. Again, my case in point is KCLU, which started as a little Thousand Oaks/Ventura station, then became a South Coast station by adding two Santa Barbara signals. Now, by adding another full-size signal in Santa Maria (KCLM/89.7), plus a translator in San Luis Obispo, KCLU is almost as much a Central Coast station, at least in terms of geographic coverage. Still, I’m not sure that’s what they have in mind. They identify now as “NPR for the California Coast,” yet their vision is still “to inform, educate and promote dialogue among the citizens of Ventura and Santa Barbara counties on local, regional, national and global issues.” No mention of San Luis Obispo County; so I’m not sure how well that’s working yet. KCBX, from San Luis Obispo, also didn’t become any less a Central Coast station when it added its South Coast signal in Santa Barbara. KCLU does talk up the Central Coast as much as it can, so maybe a shift is in the works. It’s worth noting that Santa Barbara–Santa Maria-San Luis Obispo is a Nielsen Designated Market Area (or DMA). Ventura and Thousand Oaks are part of the Los Angeles DMA.(DMAs are determined by what local TV stations are most watched. So, while what defines local and regional identity is an open question, it’s clear to me that public radio is playing a part in answering it.

I may add to those points as I take in reader feedback and think more on all of it. Meanwhile, let’s look a bit more closely to what has happened to public radio in Santa Barbara over in the current millennium.

When I moved to Santa Barbara in 2001, public radio was long on classical music and short on news and talk. The two classical stations were USC’s KQSC/88.7 with 12,000 watts and KDB/93.7 with 12,500 watts (that’s a lot), both on Gibraltar peak, overlooking town. KQSC was a repeater for KUSC in Los Angeles. On the talk (NPR, etc.) side, KCLU/88.3 had a 4-watt translator operating on 102.3 from Gibraltar Peak, overlooking town. It actually sounded pretty good if you were within sight of the transmitter, and may already have been a strong ratings contender. (I recall a Nielsen survey a few years ago that put it at #1 at the time.) To put this little translator’s size in perspective, the biggest station in town is KRUZ/103.3 KVYB/103.3, grandfathered with 105,000 watts and radiating from Broadcast Peak, which is over 4000 feet high. Here’s a pair of maps that shows the difference:

KCLU’s home signal from Thousand Oaks was weak and distant back then, and still is. So was, and is, KCRU/88.1, the Oxnard repeater for Santa Monica-based KCRW/89.9. KCRW also had a 10-watt translator on 106.9 serving Goleta (the next town west of Santa Barbara). Pacifica’s L.A. based KPFK/90.7 had a 10-watt translator on 98.7. UCSB had KCSB/91.9, its own non-NPR college station, radiating with 620 watts from Broadcast Peak, also on the Goleta side of town. I also loved that there was a local non-political full-service commercial news/talk station in town at the time: KEYT/1250am, featuring a good morning show hosted by John Palminteri.

Since then, all this happened:

- In 2002, KSBX/89.5 came on the air from Gibraltar Peak. It’s a 50-watt repeater for KCBX/90.1, the public radio voice of San Luis Obispo. On the same channel, KPBS from San Diego also pounds into town on warm days.

- In 2003, KEYT and KEYT-AM were sold, the AM station went to Spanish broadcaster, and John Palminteri spread his reporting talents across lots of other stations (including KCLU). Local news/talk was then gone until…

- In 2005, the Santa Barbara News-Press, owned by Wendy P. McCaw, got its own local AM station, now called KZSB/1290, and has been a local old-fashioned commercial ‘full service” news station ever since. The main personality there is “Baron” Ron Herron, who had been a local radio personality for many decades before then, and has persisted ever since. It’s basically his station.

- In 2008, KCLU bought a local station on the AM band. That’s now KCLU-AM/1340. Though only 650 watts, it does cover the populated South Coast pretty well.

- In 2014, a bunch of things happened at once:

- Public radio, which had never been a native thing in Santa Barbara, suddenly got saturated (as Matt Welsh put it in The Independent). Specifically…

- KPCC/89.3 in Pasadena/Los Angeles came on with a 10-watt Gibraltar Peak translator on 89.9. It covers the town well.

- Santa Monica Community College, which owns KCRW, bought KQSC from USC and made it KDRW, which has a local studio and does some local coverage, though most of the time it’s a repeater for KCRW. A big one, too.

- The University of Southern California bought KDB and moved KUSC’s classical programming over there from what had been KQSC (and is now KDRW).

- KCLU replaced its non-directional 4-watt signal on 102.3 with a new directional one that maxes at 115 watts toward downtown, but radiates as little as 5 watts in other directions. This is the signal that produces the small signal footprint in the maps above. And it rocks in the ratings.

- Along the way, local journalism flourished online as well. The Independent, a weekly, has remained a strong local institution. Edhat (founded and led by the late and still much-missed Peter Sklar) was born and became an exemplary “placeblog.” Bill MacFadyen’s Noozhawk also became a local news institution. And the News-Press didn’t die.

If I had more time, I’d put all that stuff in a graphic.

†Explanations, qualifications and cautions

Shares, Nielsen explains, are “quarter hour rating (AQH) share of persons, ages 12+, Monday through Sunday in the Metro Survey Area. A share is the percentage of those listening to radio in the MSA who are listening to a particular radio station. Average Quarter-Hour Persons (AQH Persons) is the average number of persons listening to a particular station for at least five minutes during a 15-minute period. [AQH Persons to a Station / AQH Persons to All Stations] x 100 = Share (%)”

The latest rating period differs by market. In big markets, surveys are monthly. The most recent for those are February 2019. Some are quarterly, or twice annually (Spring and Fall). The most recent of those are Fall 2018 in some cases (e.g. Hudson Valley, measured quarterly, and Santa Barbara, measured Spring and Fall), and Winter 2019 in other cases (e.g. Louisville, measured quarterly).

Noncommercial stations are not listed for all markets, and not every time in all of those where they are surveyed. For example, the listings for Santa Barbara noncommercial stations say “N/A” for the three survey periods prior to the latest one (Fall 2018), while the current listings for Monterey-Salinas (Winter 2019) list noncommercial stations as “N/A” while showing them in Fall 2018. So for Monterey-Salinas, I used the Fall 2018 listing. (The 7.7 there was just one station: KAZU, which was also #2 overall.)

In all markets there is lots of listening to radio stations not listed in the surveys. For example, all the listed shares for New York stations totaled 88.4, while Tampa-St. Petersburg stations totaled only 24.1. That means 11.8 of New York and 75.9% of Tampa-St. Pete listening is to stations not listed in the ratings. I am sure in many markets noncommercial listening is part of that dark matter, but there’s no way to tell.

In some cases, the only stations appearing in a survey are those of one or two owners. The Grand Junction survey lists only seven stations, five owned by Townsquare Media and two by Public Broadcasting of Colorado. The total of those is only 28.7. The Monroe Louisiana survey lists only six stations, all owned by Holladay Broadcasting. Those total 50.6, which means half of the listening in that market is to unlisted stations, and (presumably), ones not owned by Holladay Broadcasting.

Some stations’ online streams do make survey listings in some markets. I don’t know whether Nielsen counts listeners physically located outside a market, or how Nielsen deals with smart speakers. I do know that Nielsen cares about streaming, though, because their home page says so.

Okay, I’ve already said too much, and I have much more I could say. But this post has been sitting half-written in my browser since I started digging online one sleepless night in early March, so I’ll call it done enough and put it up.

Leave a Reply