A few weeks ago, in Where journalism fails, I wrote about how journalism, for all its high-minded (and essential) purposes, is still interested only in stories. I explained that stories have just three requirements—character, problem, and movement—and that, by focusing on those three requirements alone, journalism excludes a boundless volume of facts, many of which actually matter. I also point out that story-telling is vulnerable to manipulation by experts at feeding journalism’s appetites.

In this post my focus is on the near-infinite abundance of stories that have never been told, have been forgotten, or both, but some of which might still matter to somebody, or to the world.

You’ll find pointers to billions of those in cemeteries. Every headstone marks the absence of countless stories as lost and buried as the graves’ occupants. All the long-buried were characters in their own lives’ stories, and within each of those lives were countless other stories. But the characters in those stories are gone, their problems are over, and movement has ceased. All have been, or will soon be, erased by time and growing disinterests of the living—even of surviving friends and heirs.

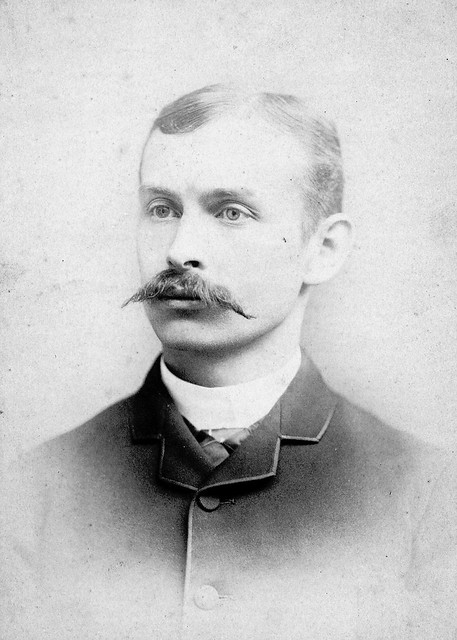

So I want to surface a few stories of deceased ancestors and relatives of my own, whose bodies are among the 300,000+ occupants of just one cemetery: Woodlawn, in The Bronx, New York. We’ll start with my great-grandfather, Henry Roman Englert. That’s him with his first four daughters, above. Clockwise from top left are Loretto (“Loretta”), Regina (“Gene”), Ethel (my grandma Searls), and Florence. Here’s Henry as a younger man:

Here are the same four girls in the top picture, at the Jersey shore in 1953, ten years after Henry died:

All those ladies lived long full lives. The longest was Grandma (second from right), who made it to a few days short of 108.

Here’s henry his granddaughter, Grace (née Searls) Apgar, my father’s sister, ten years before that:

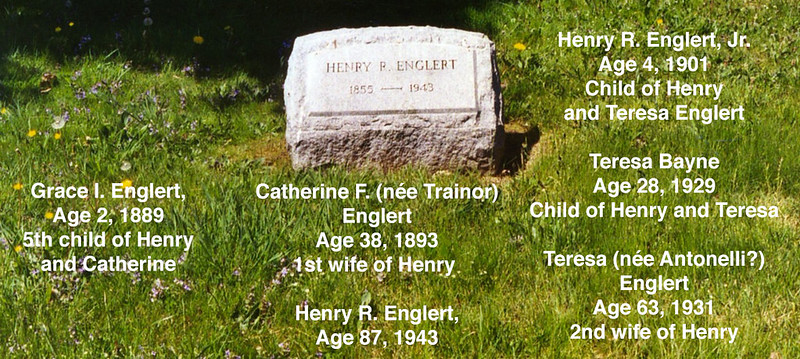

And here is his headstone, placed ten years after the shot above:

Henry was a fastidious dude, meaning highly disciplinary as well as disciplined. Grandma told a story about how her father, on arriving home from work, would summon his four daughters (of which she was one) to appear and stand in a row… He would then run his white glove over some horizontal surface and wipe it on a white shoulder of a daughter’s dress, expecting no dust to leave a mark on either glove or girl.

Henry was the son of German immigrants: Christian Englert and Jacobina Rung, both of Alsace, then of Bavaria and now part of France. They were brewers, and had a tavern on the east side of Manhattan on 110th Street. (Though an 1870 census page calls Christian a “laborer.”) Jacobina was a Third Order Carmelite nun, and was buried in its brown robes. Both were born in 1825. Christian is said to have died in 1886 while picking hops in Utica. Jacobina died in 1904.

Here’s more:

- Henry was sometimes called “HRE.”

- He headed (or was said to have headed) the Steel and Copper Plate Engravers Union in New York—and was put out of business by mechanization, like many others in his trade. I don’t know what else he did after that. Perhaps he lived off savings.

- He was what his daughter (my grandma) called a “good socialist.”

- He had at least seven daughters and one son (Henry Jr., known as Harry, who died at age four).

- He was married twice, and outlived both his wives and three of his kids, all by long margins.

- His second wife, Teresa, was (again, by lore) both an alcoholic and kinda crazy. Still, she produced several children.

- It was said that he died after having his first dentistry—a tooth pulled, at age 87. I don’t know if that was correct, but it’s one story about him.

- He rarely visited the families of children by his first wife: the Knoebels (by daughter Regina, known as Gene), the Searls (by daughter Ethel, my grandma) or the Dwyers (by daughter Florence), though there seem to be plenty of pictures of him with those families.

- Nobody alive can say why the graves of the wives and kids buried with him are unmarked, or why Henry’s is the only headstone. Here’s some detail on who lies where in his plot:

My grandmother and her sisters used to take their families on picnic trips to this plot when it was unmarked. Why did they not mark it before Henry died? Nobody who knew is alive to say.

About 80 feet away is an older three-grave plot occupied by Henry’s parents, plus one of his brothers and three cousins and in-laws named Fehn*:

Woodlawn’s own records say this about the distribution of the graves and their occupants

Left:

- Theresa M. Fen, 10 mos 8/2/1887

- Agnes Fen, 1 yr

Center:

- Annie T. Englert, 29 yrs, 4/12/1881 Bellview Hosp. NYC

- Christian Englert, 60 yrs, 10/4/1886, 16 Devereux St. Utica, NY

- Jacobina Englert, 78 yrs & 7′ deep, 3/1/04 110 e. 106th St. NYC

Right:

- Christian P. Englert, 33 yrs 4/12/1891 Bellview Hosp. NYC

- Henry W. Fehn, 85 yrs 10/23/1948 Am Vet

A hmm here: to bury Jacobina 7 feet deep, they surely would have had to dig past her husband (dead 18 years) and daughter (dead 23 years), and to have encountered bones along the way. I can say that, because I’ve seen evidence—

—that bones survive well in glacial till (about which more later). So I suspect that this three-person grave is seven feet deep, with the final occupant stacked on top.

Also, since Jacobina was a Carmelite nun, I call her “Nun of the Below.”

Further digging of the research kind, done my my aunt Katherine (née Dwyer) Burns (daughter of Florence Englert), turns up an 1870 census page that says this about the Englert family at that time:

- Christian, from Bavaria, a laborer, age 45

- Jacobina, from Bavaria, “keeps houses,” age 45

- Henry, “(illegible) engraver,” age 15

- Christian, age 12

- Annie, age 9

- Mary, age 7*

- Andrew, age 4

*Mary, I gather, married a Fehn. Here’s a clue. [Later…] Ah! I found a better one:

Mary A Fehn (born Englert), 1863 – 1957

- Mary, A Fehn was born on month day 1863, at birth place, New York, to Christian Englert and Jacobina Englert

- Mary had 4 siblings: Henry Roman Englert and 3 other siblings.

- Mary married Henry Fehn circa 1885, at age 21 at marriage place, New York.

- They had 5 children: Agnes Fehn, Therese Fehn and 3 other children.

- Mary passed away on month day 1957, at age 94 at death place, New York.

(This is from Geni.com, which wants money to reveal details at those links.)

Mostly I’m impressed that, among Christian and Jacobina’s kids, Mary and Henry alone lived long lives.

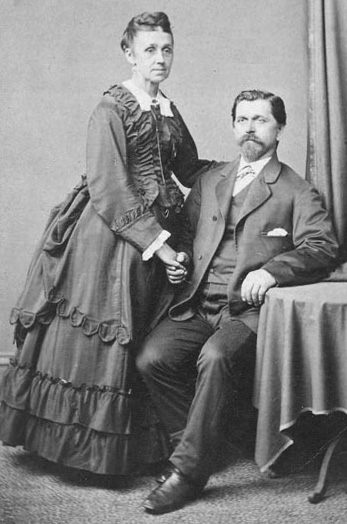

Here are Christian and Jacobina, in life, perhaps around the time of the 1870 census:

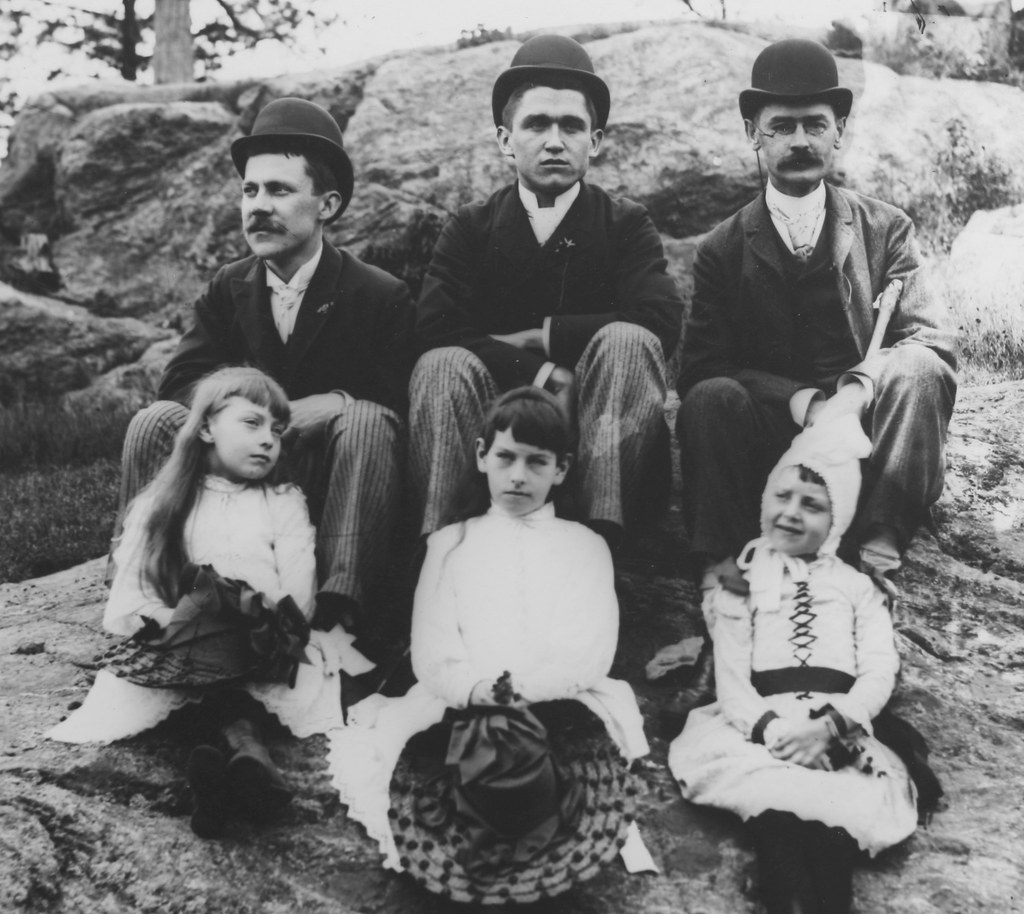

And here are their three sons, with Henry’s first three daughters, the future Grandma Searls on the right:

There are differences between the caption I wrote under that photo eight years ago (based on what I knew, or thought I knew, at the time), Grace’s comment below it, posted when she was 100 years old. (Grace rocked. Here’s her 100th birthday party, in Maine.) In that comment, Grace says she thinks the one on the left is Andrew, and the one in the middle is Christopher, by which I’m sure she means Christian (the younger). Both died not long after this photo was taken. Not clear whether Christian or Andrew was the one who died of a terminal cold acquired while working in a frozen food warehouse or something.

While he’s not in the Englert plot above, he is in an unmarked one nearby, which Woodlawn identifies thus:

- Andrew J. Englert, 35 yrs, 5/29/1901

- Annie C. Englert, 67 yrs, 11/17/1935

I suppose, since his sister Annie (named Anna) is buried with her parents and brother Christian (among various Fehns), that she was Andrew’s wife. Here is a shot of that grave.

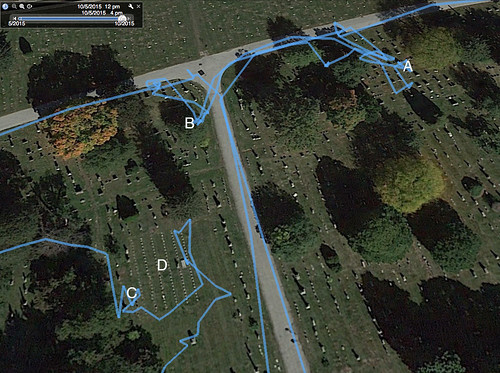

And here is a Google Earth GPS trace of a visit to all three gravesites: Henry at B, his parents Christian and Jacobina + sibs Anna (Annie) and Christian at A, and Andrew + (wife?) Annie at C:

At D in that shot is a collection of headstones for New York’s Association for the Relief of Respectable Aged Indigent Females, which occupied a beautiful Victorian gothic building in Harlem that is now home to a youth hostel. The Wikipedia entry at the last link fails to mention the cemetery. (I should correct that.)

Last is the Knoebel plot, nearby. Bigger than any of the Englert plots, it is first in a way, because Regina Knoebel was the Eldest of Henry Englert’s many children. It looks like this:

From the caption under that photo:

The six-grave, twelve-body Knoebel plot is described by Woodlawn Cemetery here. Since the descriptions of those graves that don’t quite agree with some of the headstones (for example, with spellings), I’ve combined the two in the description below.

First, behind the main monument are three graves. Left to right, they are—

1

Lillian (Lillie) Raichle, 1876-3/3/1958, 81 years

Lillian W. Raichle, 1902-1907, 5 years

Herman Raichle, 1877-19332

Sarah Bladen, 1864 to 1926, 61 years3

Henry Vier, 8 years

Rita P. Knoebel, 81 years, 2/15/92All three have headstones.

In front of the monument are three more graves, left to right, those are:

4

John E. Knoebel, 78 years 9/4/50

John E. Knoebel, 84 years, 12/25/2000

Regina Knoebel, 80 years, 1/6/1960, exhumed on 10/7/70 and reburied in Fairview Cemetery in New Jersey5

John E. Knoebel, 61 years6

Louis F. Knoebel, 50 years, 11/11/2013

Anastasia Knoebel, 60 yearsNote that grave 4 is a bit sunken. This is the one from which Regina (née Englert) Knoebel (Aunt Gene), who was married to one of the John E. (“Johnny”) Knoebels, and whose son John E. was, apparently, buried in her stead.

A story I recall about Aunt Gene is almost certainly apocryphal, but still interesting, is that she once climbed a spire of rock in New Jersey’s Palisades and carved her initials, “RE,” near the top—and that these were later visible from the George Washington Bridge, because it was built right next to the spire. (On the North side.)

Lending credence to this story is an absent fear of heights that runs in my father’s family (his mom was Gene’s younger sister Ethel). Pop also grew up on the Palisades and was a cable rigger working on the Bridge itself. (Here he is.) And I do at least recall Aunt Gene as the most alpha (being the eldest) of the four Englert sisters; so it kinda seemed in character that she might do such a thing. But … I have no idea. I’ve been by there many times since then, and the whole face of the Palisades is so overrun with greenery now that it’s hard to tell if a spire is even there. I do recall that there was one, though.

Yet the sad but true summary of all this is that today none of these people matter much to anybody, even though most or all of them mattered to others a great deal when they were alive. Living relatives, including me, are all way too busy with stories of their own, and long since past caring much, if at all, about any of the departed here.

A measure of caring about the preservation of graves at Woodlawn is whether or not the headstone is “endowed,” meaning maintained in its original upright and above-ground condition. The elder Englerts’ stone, as we see in the shot above, is endowed. Henry’s, I suppose, is not, but appears to be holding up. So far.

Many of those not endowed are sinking into the Earth. See the examples here, here and here. The last of those is this:

The gravestone business calls its products memorials, defined as “something, especially a structure, established to remind people of a person or event.” The headstone above may have reminded some people a century ago of Henry Kremer and his infant namesake, but today I find nothing about either online. And soon this stone, like so many others around it, will be buried no less than the graves they once marked, simply because most of Woodlawn, like much of New York City itself, is barely settled glacial till, and so soft you can dig it with a spoon. (In fact, New York’s glacial history is far more interesting today than the lives of nearly all the inhabitants of its cemeteries. That’s why it makes the great story at that last link.)

Archeology is “the study of human history and prehistory through the excavation of sites and the analysis of artifacts and other physical remains.” These days we do much of that online, in digital space. It’s what I’m doing here, in some faith that at least a few small bits of what I tossed out in the paragraphs above will prove useful to story-tellers among the living.

And I suggest that this, and not just telling the usual stories, needs to be a bigger part of journalism’s calling in our time.

Leave a Reply