There is latency to everything. Pain, for example. Nerve impulses from pain sensors travel at about two feet per second. That’s why we wait for the pain when we stub a toe. The crack of a bat on a playing field takes half a second before we hear it in the watching crowd. The sunlight we see on Earth is eight minutes old. Most of this doesn’t matter to us, or if it does we adjust to it.

Likewise with how we adjust to the inverse square law. That law is why the farther away something is, the smaller it looks or the fainter it sounds. How much smaller or fainter is something we intuit more than we calculate? Can’t say. But what we can is that we understand the inverse square law with our bodies. Just like everything else.

All our deepest, most unconscious metaphors start with our bodies. That’s why we grasp, catch, toss around, or throw away an idea. It’s also why nearly all our prepositions pertain to location or movement. Over, under, around, through, with, beside, within, alongside, on, off, above and below only make sense to us because we have experienced them with our bodies.

So::: How are we to make full sense of the Web, or the Internet, where we are hardly embodied at all?

We may say we are on the Web because we need it to make sense to us as embodied beings. Yet we are only looking at a manifestation of it.

The “it” is the hypertext protocol (http) that Tim Berners-Lee thought up in 1990 so high energy physicists, scattered about the world, could look at documents together. That protocol ran on another one: TCP/IP. Together they were mannered talk among computers about how to show the same document across any connection over any collection of networks between any two endpoints, regardless of who owned or controlled those networks. In doing so, Tim rubbed a bottle of the world’s disparate networks. Out popped the genie we call the Web, ready to grant boundless wishes that only began with document sharing.

This was a miracle humbling loaves and fish: a miracle so new and so odd that the movie Blade Runner, which imagined in 1982 that Los Angeles in 2019 would feature floating cars, off-world colonies, and human replicants, failed to foresee a future when anyone could meet with anyone else, or any group, anywhere in the world, on wish-granting slabs they could put on their desks, laps, walls, or hold in their hands. (Instead Blade Runner imagined there would still be pay phones and computers with vacuum tubes for screens.)

This week I attended Web Science 20 on my personal slab in California, instead of what was planned originally: in the flesh at the University of Southampton in the UK. It was still a conference, but now a virtual one, comprised of many people on many slabs, all over the world, each with no sense of distance any more meaningful than those imposed by the inconvenience of time zones.

Joyce (my wife, who is also the source of much wisdom for which her husband gets the credit) says our experience on the Web is one of absent distance and gravity—and that this experience is still so new to us that we have only begun to make full sense of it as embodied creatures. We’ll adjust, she says, much as astronauts adjust to the absence of gravity; but it will take more time than we’ve had so far. Meanwhile, we may become experts at using the likes of Zoom, but that doesn’t mean we operate in full comprehension of the new digital environment we co-occupy.

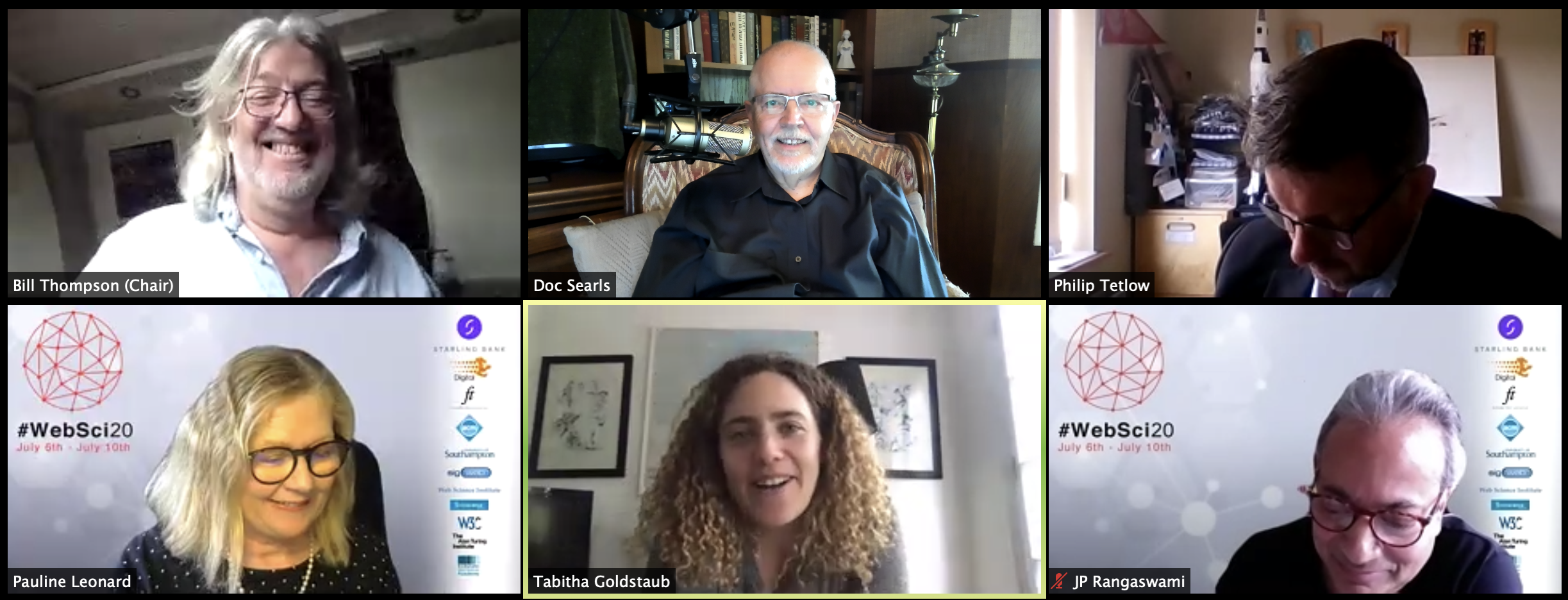

My panel at WebSci20 was comprised of six people, plus others asking questions in a chat, during the closing session of the conference. (That’s us, at the top of this post.) The title of our session was The Future of Web Science. To prep for that session, I wrote the first draft of what follows: a series of thoughts I hoped to bring up in the session, plus some I actually did.

The first thought is the one I just introduced: The Web, like the Net it runs on, is both new and utterly vexing toward understanding in terms we’ve developed for making sense of embodied existence.

Here are some more.

The Web is a whiteboard.

In the beginning, we thought of the Web as something of a library, mostly because it was comprised of sites with addresses and pages that were authored, published, syndicated, browsed, and read. A universal resource locator, better known as a URL, would lead us through what an operating system calls a path or a directory, much as a card catalog did before library systems went digital. It also helped that we understood the Web as real estate, with sites and domains that one owned and others could visit.

The metaphor of the Web as a library, though useful, also misdirects our attention and understanding away from its nature as a collection of temporary manifestations. Because, for all we attempt to give the Web a sense of permanence, it is evanescent, temporary, and ephemeral. We write and publish there as we might on snow, sand or a whiteboard. Even the websites we are said to “own” are in fact only rented. Fail to pay the registrar and off it goes.

The Web is not what’s on it.

It is not Google, Facebook, dot-anything, or dot-anybody. It is the manifestation of documents and other non-stuff we call “content,” presented to us in browsers and whatever else we invent to see and deal with what the hypertext protocol makes possible. Here is how David Weinberger and I put it in World of Ends, more than seventeen years ago:

1. The Internet isn’t complicated

2. The Internet isn’t a thing. It’s an agreement.

3. The Internet is stupid.

4. Adding value to the Internet lowers its value.

5. All the Internet’s value grows on its edges.

6. Money moves to the suburbs.

7. The end of the world? Nah, the world of ends.

8. The Internet’s three virtues:

a. No one owns it

b. Everyone can use it

c. Anyone can improve it

9. If the Internet is so simple, why have so many been so boneheaded about it?

10. Some mistakes we can stop making already

That was a follow-up of sorts to The Cluetrain Manifesto, which we co-wrote with two other guys four years earlier. We followed up both five years ago with an appendix to Cluetrain called New Clues. While I doubt we’d say any of that stuff the same way today, the heart of it beats the same.

The Web is free.

The online advertising industry likes to claim the “free Internet” is a grace of advertising that is “relevant,” “personalized,” “interest-based,” “interactive” and other adjectives that misdirect us away from what those forms of advertising actually do, which is track us like marked animals.

That claim, of course, is bullshit. Here’s what Harry Frankfurt says about that in his canonical work, On Bullshit (Cambridge University Press, 1988): “The realms of advertising and public relations, and the nowadays closely related realm of politics, are replete with instances of bullshit so unmitigated that they can serve among the most indisputable and classic paradigms of the concept.” Boiled down, bullshit is what Wikipedia (at the moment, itself being evanescent) calls “speech intended to persuade without regard for truth.” Another distinction: “The liar cares about the truth and attempts to hide it; the bullshitter doesn’t care if what they say is true or false, but rather only cares whether their listener is persuaded.”

Consider for a moment Win Bigly: Persuasion in a World Where Facts Don’t Matter, a 2017 book by Scott Adams that explains, among other things, how a certain U.S. tycoon got his ass elected President. The world Scott talks about is the Web.

Nothing in the history of invention is more supportive of bullshit than the Web. Nor is anything more supportive of truth-telling, education and damned near everything else one can do in the civilized world. And we’re only beginning to discover and make sense of all those possibilities.

We’re all digital now

Meaning not just physical. This is what’s new, not just to human experience, but to human existence.

Marshall McLuhan calls our technologies, including our media, extensions of our bodily selves. Consider how, when you ride a bike or drive a car, those are my wheels and my brakes. Our senses extend outward to suffuse our tools and other technologies, making them parts of our larger selves. Michael Polanyi called this process indwelling.

Think about how, although we are not really on or through the Web, we do dwell in it when we read, write, speak, watch and perform there. That is what I am doing right now, while I type what I see on a screen in San Marino, California, as a machine, presumably in Cambridge, Massachusetts, records my keystrokes and presents them back to me, and now you are reading it, somewhere else in (or on, or choose your preposition) the world. Dwell may be the best verb for what each of us are doing in the non-here we all co-occupy in this novel (to the physical world) non-place and time.

McLuhan also said media revolutions are formal causes. Meaning that they form us. (He got that one from Aristotle.) In different ways, we were formed and re-formed by speech, writing, printing, and radio and television broadcasting.

I submit that we are far more formed by digital technologies, and especially by the Internet and the Web, than by any other prior technical revolution. (A friend calls our current revolution “the biggest thing since oxygenation.”)

But this is hard to see because, as McLuhan puts it, every one of these major revolutions becomes a ground on which everything else dances as figures. But it is essential to recognize that the figures are not the ground. This, I suggest, is the biggest challenge for Web Science.

It’s damned hard to study ground-level formal causes such as digital tech, the Net, and the Web. Because what they are technically is not what they do formally. They are rising tides that float all boats, in oblivity to the boats themselves.

I could say more, and I’m sure I will, but I want to get this much out there before the panel.

Leave a Reply