There’s an economic theory here: Free customers are more valuable than captive ones—to themselves, to the companies they deal with, and to the marketplace. If that’s true, the intention economy will prove it. If not, we’ll stay stuck in the attention economy, where the belief that captive customers are more valuable than free ones prevails.

Let me explain.

The attention economy is not native to human attention. It’s native to businesses that seek to grab and manipulate buyers’ attention. This includes the businesses themselves and their agents. Both see human attention as a “resource” as passive and ready for extraction as oil and coal. The primary actors in this economy—purveyors and customers of marketing and advertising services—typically talk about human beings not only as mere “users” and “consumers,” but as “targets” to “acquire,” “manage,” “control” and “lock in.” They are also oblivious to the irony that this is the same language used by those who own cattle and slaves.

While attention-grabbing has been around for as long as we’ve had yelling, in our digital age the fields of practice (abbreviated martech and adtech) have become so vast and varied that nobody (really, nobody) can get their head around everything that’s going on in them. (Examples of attempts are here, here and here.)

One thing we know for sure is that martech and adtech rationalize taking advantage of absent personal privacy tech in the hands of their targets. What we need there are the digital equivalents of the privacy tech we call clothing and shelter in the physical world. We also need means to signal our privacy preferences, to obtain agreements to those, and to audit compliance and resolve disputes. As it stands in the attention economy, privacy is a weak promise made separately by websites and services that are highly incentivised not to provide it. Tracking prophylaxis in browsers is some help, but itworks differently for every browser and it’s hard to tell what’s actually going on.

Another thing we know for sure is that the attention economy is thick with fraud, malware, and worse. For a view of how much worse, look at any adtech-supported website through PageXray and see the hundreds or thousands of ways sthe site and its invisible partners are trying to track you. (For example, here’s what Smithsonian Magazine‘s site does.)

We also know that lawmaking to stop adtech’s harms (e.g. GDPR and CCPA) has thus far mostly caused inconvenience for you and me (how many “consent” notices have interrupted your web surfing today?)—while creating a vast new industry devoted to making tracking as easy as legally possible. Look up GDPR+compliance and you’ll get way over 100 million results. Almost all of those will be for companies selling other companies ways to obey the letter of privacy law while violating its spirit.

Yet all that bad shit is also a red herring, misdirecting attention away from the inefficiencies of an economy that depends on unwelcome surveillance and algorithmic guesswork about what people might want.

Think about this: even if you apply all the machine learning and artificial intelligence in the world to all the personal data that might be harvested, you still can’t beat what’s possible when the targets of that surveillance have their own ways to contact and inform sellers of what they actually want and don’t want, plus ways to form genuine relationships and express genuine (rather than coerced) loyalty, and to do all of that at scale.

We don’t have that yet. But when we do, it will be an intention economy. Here are the opening paragraphs of The Intention Economy: When Customers Take Charge (Harvard Business Review Press, 2012):

This book stands with the customer. This is out of necessity, not sympathy. Over the coming years, customers will be emancipated from systems built to control them. They will become free and independent actors in the marketplace, equipped to tell vendors what they want, how they want it, where and when—even how much they’d like to pay—outside of any vendor’s system of customer control. Customers will be able to form and break relationships with vendors, on customers’ own terms, and not just on the take-it-or-leave-it terms that have been pro forma since Industry won the Industrial Revolution.

Customer power will be personal, not just collective. Each customer will come to market equipped with his or her own means for collecting and storing personal data, expressing demand, making choices, setting preferences, proffering terms of engagement, offering payments and participating in relationships—whether those relationships are shallow or deep, and whether they last for moments or years. Those means will be standardized. No vendor will control them.

Demand will no longer be expressed only in the forms of cash, collective appetites, or the inferences of crunched data over which the individual has little or no control. Demand will be personal. This means customers will be in charge of personal information they share with all parties, including vendors.

Customers will have their own means for storing and sharing their own data, and their own tools for engaging with vendors and other parties. With these tools customers will run their own loyalty programs—ones in which vendors will be the members. Customers will no longer need to carry around vendor-issued loyalty cards and key tags. This means vendors’ loyalty programs will be based on genuine loyalty by customers, and will benefit from a far greater range of information than tracking customer behavior alone can provide.

Thus relationship management will go both ways. Just as vendors today are able to manage relationships with customers and third parties, customers tomorrow will be able to manage relationships with vendors and fourth parties, which are companies that serve as agents of customer demand, from the customer’s side of the marketplace.

Relationships between customers and vendors will be voluntary and genuine, with loyalty anchored in mutual respect and concern, rather than coercion. So, rather than “targeting,” “capturing,” “acquiring,” “managing,” “locking in” and “owning” customers, as if they were slaves or cattle, vendors will earn the respect of customers who are now free to bring far more to the market’s table than the old vendor-based systems ever contemplated, much less allowed.

Likewise, rather than guessing what might get the attention of consumers—or what might “drive” them like cattle—vendors will respond to actual intentions of customers. Once customers’ expressions of intent become abundant and clear, the range of economic interplay between supply and demand will widen, and its sum will increase. The result we will call the Intention Economy.

This new economy will outperform the Attention Economy that has shaped marketing and sales since the dawn of advertising. Customer intentions, well-expressed and understood, will improve marketing and sales, because both will work with better information, and both will be spared the cost and effort wasted on guesses about what customers might want, and flooding media with messages that miss their marks. Advertising will also improve.

The volume, variety and relevance of information coming from customers in the Intention Economy will strip the gears of systems built for controlling customer behavior, or for limiting customer input. The quality of that information will also obsolete or re-purpose the guesswork mills of marketing, fed by crumb-trails of data shed by customers’ mobile gear and Web browsers. “Mining” of customer data will still be useful to vendors, though less so than intention-based data provided directly by customers.

In economic terms, there will be high opportunity costs for vendors that ignore useful signaling coming from customers. There will also be high opportunity gains for companies that take advantage of growing customer independence and empowerment.

But this hasn’t happened yet. Why?

Let’s start with supply and demand, which is roughly about price. Wikipedia: “the relationship between the price of a given good or product and the willingness of people to either buy or sell it.” But that wasn’t the original idea. “Supply and demand” was first expressed as “demand and supply” by Sir James Denham-Steuart in An Inquiry into the Principles of Political Oeconomy, written in 1767. To Sir James, demand and supply wasn’t about price. Specifically, “it must constantly appear reciprocal. If I demand a pair of shoes, the shoemaker either demands money or something else for his own use.” Also, “The nature of demand is to encourage industry.”

Nine years later, in The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith, a more visible bulb in the Scottish Enlightenment, wrote, “The real and effectual discipline which is exercised over a workman is that of his customers. It is the fear of losing their employment which restrains his frauds and corrects his negligence.” Again, nothing about price.

But neither of those guys lived to see the industrial age take off. When that happened, demand became an effect of supply, rather than a cause of it. Supply came to run whole markets on a massive scale, with makers and distributors of goods able to serve countless customers in parallel. The industrial age also ubiquitized standard-form contracts of adhesion binding all customers to one supplier with a single “agreement.”

But, had Sir James and Adam lived into the current millennium, they would have seen that it is now possible, thanks to digital technologies and the Internet, for customers to achieve scale across many companies, with efficiencies not imaginable in the pre-digital industrial age.

For example, it should be possible for a customer to express her intentions—say, “I need a stroller for twins downtown this afternoon”—to whole markets, but without being trapped inside any one company’s walled garden. In other words, not only inside Amazon, eBay or Craigslist. This is called intentcasting, and among its virtues is what Kim Cameron calls “minimum disclosure for constrained purposes” to “justifiable parties” through a choice among a “plurality of operators.”

Likewise, there is no reason why websites and services can’t agree to your privacy policy, and your terms of engagement. In legal terms, you should be able to operate as the first party, and to proffer your own terms, to which sites and services can agree (or, as privacy laws now say, consent) as second parties. That this is barely thinkable is a legacy of a time that has sadly not yet left us: one in which only companies can enjoy that kind of scale. Yet it would clearly be a convenience to have privacy as normalized in the online world as it is in the offline one. But we’re slowly getting there; for example with Customer Commons’ P2B1, aka #NoStalking term, which readers can proffer and publishers can agree agree to. It says “Just give me ads not based on tracking me.” Also with the IEEE’s P7012 Standard for Machine Readable Personal Privacy Terms working group.

Same with subscriptions. A person should be able to keep track of all her regular payments for subscription services, to keep track of new and better deals as they come along, to express to service providers her intentions toward those new deals, and to cancel or unsubscribe. There are lots of tools for this today, for example Truebill, Bobby, Money Dashboard, Mint, Subscript Me, BillTracker Pro, Trim, Subby, Card Due, Sift, SubMan, and Subscript Me. There are also subscription management systems offered by Paypal, Amazon, Apple and Google (e.g. with Google Sheets and Google Doc templates). But all of them to one degree or another are based more on the felt need by those suppliers for customer captivity than for customer independence.

As Customer Commons unpacks it here, there are many largely or entirely empty market spaces that are wide open for free and independent customers: identity, shopping (e.g. with shopping carts of your own to take from site to site), loyalty (of the genuine kind), property ownership (the real Internet of Things), and payments, for example.

It is possible to fill all those spaces if we have the capacity to—as Sir James put it—encourage industry, restrain fraud and correct negligence. While there is some progress in some of those areas, the going is still slow on the global scale. After all, The Intention Economy is nine years old and we still don’t have it yet. Is it just not possible, or are we starting in the wrong places?

I think it’s the latter.

Way back in 1995, when the Internet first showed up on both of our desktops, my wife Joyce said, “The sweet spot of the Internet isn’t global. It’s local.” That was the gist of my TEDx Santa Barbara talk in 2018. It’s also why Joyce and I are now in Bloomington, Indiana, working with the Ostrom Workshop at Indiana University on deploying a new way for demand and supply to inform each other and get business rolling—and to start locally. It’s called the Byway, and it works outside of the old supply-controlled industrial model. Here’s an FAQ. Please feel free to add questions in the comments here.

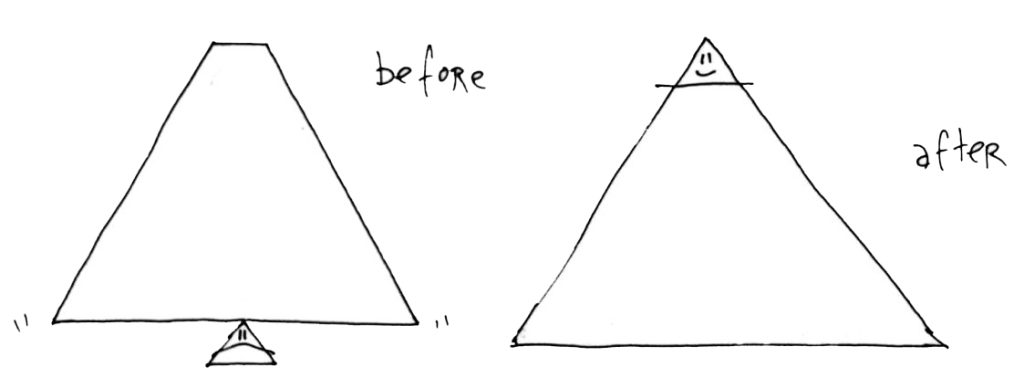

The title image is by the great Hugh Macleod, and was commissioned in 2004 for a startup he and I both served and is now long gone.

Leave a Reply