Notes from William Brewster: Signs of Spring

Here in the Greater Boston area we’ve had a week or so of beautiful spring weather. Robins are out foraging over soft ground, Red-winged Blackbirds flash their wings in wetland areas, and Song Sparrows are singing again. While we’re still likely to have more cold snaps and snow, we’re definitely feeling the season shift.

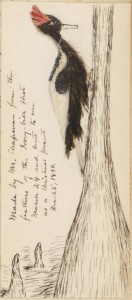

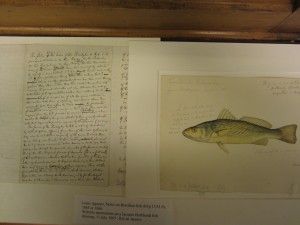

For ornithologist William Brewster, a productive day’s work often looked like a long ramble outside with a notebook and a gun, or later on, a notebook and a pair of binoculars. His daily journal entries often run many pages long as he notes the places he visited and every natural detail that stood out to him.

On March 25, 1891, Brewster spent the day riding and walking from Lexington to Belmont with a friend, and noted many of the signs of spring that we’re seeing this week.

Song Sparrow, photographed in Sagamore, Mass.

Red-winged Blackbird, singing and displaying, photographed in Milton, Mass. Photos courtesy of Evan Lipton. © Evan Lipton 2013 and 2015.

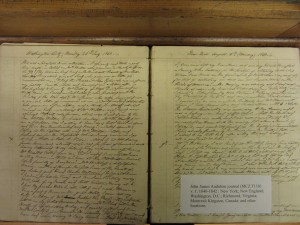

(This journal entry has been abridged and broken into shorter paragraphs for readability.)

March 25, 1891

Started at 8.20 this morning with F. Bolles and drove to the Bryant farm in Lexington. The past six days have been cloudy and dismal with snow, sleet, and rain falling much of the time, but this morning the sun rose clear and there was a light breeze from the N. W. which by 9 a.m. had increased to a typical March wind, roaring through the leafless woods, ruffling the most sheltered forest roads and beating the tall, withered meadow grass savagely to and fro.

The greater part of the day, however, was just warm enough to be delightful, especially in openings in the woods and on sheltered hillsides. The air was bracing but at no time raw and there was a smell of earth mould and wet leaves. In short Spring was in the air.

The roads were dry and hard in most places and the grass tinged with green on sunny exposures while about spring holes it was vivid green. There is little snow or ice left except under evergreens in the woods and on the north side of high banks. The ground is still very wet and sodden and there is hard frost under the leaves everywhere in the woods.

We heard a Bluebird or two before reaching Waverly and two Song Sparrows, one opposite the Adams place being an exceptionally fine singer. As the horse was walking slowly up the steep pitch past the lower mill pond there was a sudden whirring of wings behind us on the right and a bevy of twelve Quail hurtled over our heads like a shower of cannon balls. They crossed the ravine just below the house and disappeared over the knolls beyond flying very fast and nearly 100 feet above the earth when above the bed of Beaver Brook. What disturbed them I do not know; certainly not our carriage for they rose among the pines at least 100 yds. from the road.

The willows were wonderfully beautiful as we entered their eastern end, the sunlight bringing out their old gold tints and lying lovingly on the long, straight reach of road that led away across the great, half flooded meadow. There were hosts of Song Sparrows here. Indeed we must have heard nearly a dozen and others were continually flitting across the road or rustling through the dry grass on its borders. Two Rusty Blackbirds rose from the flooded meadow and alighted in the top of a maple uttering their tinkling medley.

In the woods at the western end six or eight Crows were sitting in pairs in the tops of the tall oaks. A Red-wing, the only one seen during the day, was singing in the top of a hickory under which we drove without disturbing him. We drove past the Bryant farm to the Theodore Parker place and then returned. Just before searching the Bryant farm we started a musk rat from the road where, on the edge of a pond of rain water, he was sitting in the sun. He floundered and skipped over and through the shallow water in haste and finally disappeared in a half submerged stone wall.

…

Our drive home was a fitting close to the long, restful, delightful day. As we entered the Willows the sun was setting and its level beams threw a strong light on the tops of the trees, the road itself being in shadow.

A great flock of Crows (Bolles counted forty five) straggled off in a long, swarming line northward apparently starting on a migrating flight but perhaps on the way to a roost.

A musk rat kept abreast of us for a little way clearing deep furrow in the smooth surface of the ditch on the right of the road and finally humping his back and diving so smoothly as to leave scarcely a ring on the spot where he disappeared. Near the Payson place more Crows, a small flock, starting on a flight but heading first west and then nearly south-west.

The wind blew cold and strong and the light was fading fast when we reached home at about six o’clock.

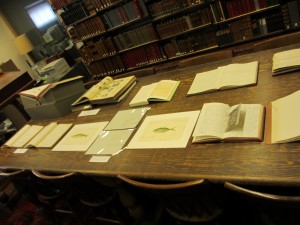

You can read the full journal entry here on the Biodiversity Heritage Library website.

If you’re not familiar with the New England spring singers noted in Brewster’s journal entry, check out the videos below.

-Elizabeth Meyer