(view as PDF) AIU 54 Blog Intro Essay

Everyone in America remembers where they were on September 11th, 2001. I remember walking home from elementary school and getting a big hug from my mom – “everything is going to be OK,” she said. I thought to myself, what’s going on? My mom took me and my two brothers inside the house and held us as we watched the footage of The Twin Towers burn down after being hit by two planes. The chaos continued after the attacks – my friend’s dad was in 2 World Trade Center. Nearly three-thousand other people lost their lives that day. Who would do something so bad to so many innocent people? Being exposed to image after image of violent terrorists and an onslaught of accusations towards Islam, I remember asking my parents at the dinner table, “why is Islam so bad?” It was not until I learned more about the attacks and the teachings of Islam that I realized that religion was not the problem. People fueled with hatred and a lack of understanding were the problem.

One of the most symbolic parts of The Reluctant Fundamentalist was when Changez told the CIA agent to “listen to the whole story from the very beginning, not just bits and pieces.” In his first lecture of the semester, Professor Ali Asani explained how people have an inability to engage with differences because of the lack of adequate tools to understand differences. They do not listen to the whole story. Citing religious illiteracy as a manifestation of this ignorance, Asani invited us with him on a journey of understanding Islam and its incredibly diverse following. Asani presented us with a cultural studies approach to studying Islam. During the lecture, Asani discussed how the cultural studies approach can help solve the problems of religious illiteracy:

“This approach considers how religion is a phenomenon that is deeply imbedded in all dimensions and contexts of the human experience. It is intricately interwoven within a complex web of contexts — historical, political, economic, social, literary, artistic, etc. It requires multiple lenses through which to understand its multivalent social/cultural influences. Conceptions of religion are dynamic; as contexts evolve and change, religious ideas and institutions change as well.”

With an increase in connectivity via faster modes of transportation and the internet, societies are becoming more globalized. Cultures are exposed to one another more than ever before. Asani, in his book Infidel of Love, explains how this proximity, instead of uniting civilizations, has created “greater misunderstandings…resulting in ever-escalating tensions between cultures and nations” (p. 1). For class, we were assigned to compile a blog of weekly responses to readings pertaining to religion, literature and art in Muslim cultures. Written in English, the goal of this blog is to spread awareness of the beauty of Islam to people in The United States – to profile the whole story of Islam. Using the aforementioned cultural studies approach to address many different facets of Muslim cultures across the world, this blog will hopefully allow people to partially overcome religious illiteracy and spark a greater interest in learning more about Muslim cultures.

While the individual blog posts respond to individual weekly readings, I am going to present some more general information to help contextualize the study of Islam. Professor Asani framed our learning of Islam with three main themes: Traditional, Post-Prophetic and Contemporary Islam. Islam is a monotheistic religion practiced by about 25% of the world’s population. Islam dates back to the early 7th century when the Prophet Muhammad – the last of God’s prophets – received divine revelations from God himself to form the Qur’an, Islam’s holy book. The word of God within the Qur’an, coupled with the Sunnah (the teachings of the Prophet) and the Hadith (accounts of the Prophet’s lifestyle) provide the framework for how Muslims are supposed to live righteous lives.

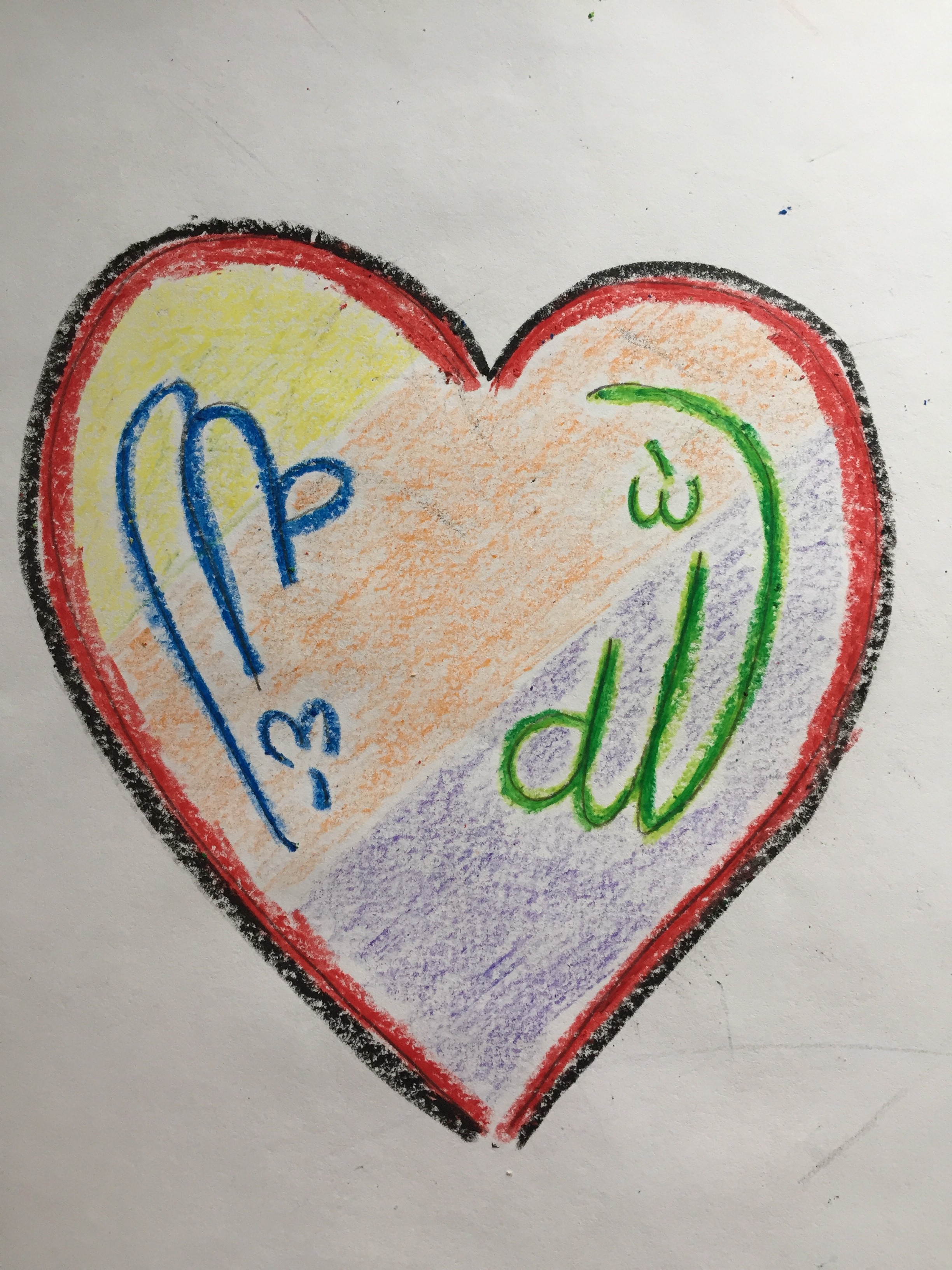

In this class, we were initially exposed to the traditional sources of Islam. The Qur’an was revealed to Muhammad by God himself via the angel Gabriel. Before the Qur’an was written down, it was passed on by oral tradition. Wanting to preserve the essence of the original recitations, Qur’anic recitations have strict rules known as tajwid, such as nazalization and shake. These recitations are highly valuable, in fact there is an annual World Qur’anic Recitation Championship in which participants are scored based on both their ability to memorize the entire Qur’an and all of the tajwid. The initially oral tradition of the Qur’an was eventually codified into a written text. Because of the beautiful, divine nature of these teachings, there became an effort to capture the orality of the Qur’an within the constraints of words. Calligraphy is a decorative way to write down words. In a previous assignment, we were asked to make an Arabic calligram of the word Allah. I have included below my interpretation of Allah and his all-encompassing love. During this assignment I learned that the beauty of calligraphy was not just in its artistic designs, but rather was how the individual gained the power to interpret the Qur’an. These traditional sources of Islam have incredible focus on the aesthetic value of their representations. For that reason, these traditional sources of Islam paved the way for the incredibly diverse aesthetic interpretations of Islam in both Post-Prophetic and Contemporary Islam.

is an annual World Qur’anic Recitation Championship in which participants are scored based on both their ability to memorize the entire Qur’an and all of the tajwid. The initially oral tradition of the Qur’an was eventually codified into a written text. Because of the beautiful, divine nature of these teachings, there became an effort to capture the orality of the Qur’an within the constraints of words. Calligraphy is a decorative way to write down words. In a previous assignment, we were asked to make an Arabic calligram of the word Allah. I have included below my interpretation of Allah and his all-encompassing love. During this assignment I learned that the beauty of calligraphy was not just in its artistic designs, but rather was how the individual gained the power to interpret the Qur’an. These traditional sources of Islam have incredible focus on the aesthetic value of their representations. For that reason, these traditional sources of Islam paved the way for the incredibly diverse aesthetic interpretations of Islam in both Post-Prophetic and Contemporary Islam.

When Muhammad died at the age of 62, Islam was forced to find a successor. This created a schism in Islam – there became Sunni and Shia Muslims. The major distinction between these two forms of Islam is how they determine the Prophet’s successor. Shia Muslims believe that Ali, the son-in-law of the Prophet, had been designated by the Prophet to be the successor. The Shia Muslims reject how Sunni Muslims believe that people themselves have authority to decide the successors of the Prophet. The struggle over who are the true spiritual leaders of Islam – whether it is the Ulama or the Imams – has led to incredible tension within the religion itself. While the majority of Muslims in the world are Sunni, there remain countries, such as Iran, in which Shia Muslims are the majority. We also learned about another form of Islam: Sufism. Sufism is a form of Islam that focuses on the mystical inner nature of the religion. Citing the Qur’an, “…We know what the innermost self whispers within him: We are closer to him than his neck vein,” Sufis look to let of the ego by focusing on God. Performing mystical dance rituals such as sama, Sufis escape the nafs (ego) by focusing on dhikr (remembrance of God). These different interpretations of Islamic framework started various different communities of interpretation within Islam. Communities of interpretation paved the way for more contemporary Muslim societies.

As time went on, cultures adapted with the rise in modernity and globalization. While cultures began to shift, Islam, like many other religions, was forced to adapt to these modern times. Asani discussed the contemporary conformations of Islam by profiling one major aspects of these changes: the feminist movement. According to his lecture on April 5th, Asani explained how both internal and external factors caused major changes in Muslim societies. Internal factors, such as the syncretism of traditionally non-Islamic customs like music and dance in Sufism and traditionally Islamic traditions questioned tawhid, the monotheistic nature of Islam. External factors such as interactions with Europe and colonization also contributed to changes in contemporary Muslim societies. Women’s bodies became a medium for Islamic political battles. As John Zaleski discussed, the veiling of women showed how women perceived the Islamic republic’s authority. In the Qur’an and the Hadith there are references to modesty and the veiling of the Prophet’s wives. However, as Amina Wadud Muhsin put it in her book Qur’an and Women:

“The Qur’an acknowledges the virtue of modesty and demonstrates it through the prevailing practices. The principle of modesty is important—not the veiling and seclusion which were manifestations particular to that context. The movement from principles to particulars can only be done by the members of whatever particular context in which a principle is to be applied.”

This excerpt highlights how within changing times, previously “traditional” concepts must also change as well. According to Amina, one cannot legitimate governing rules created centuries ago to current societies that have vastly different societal contexts. Modern-day Islam maintains its root in its traditional source. However, post-prophetic and contemporary interpretations of Islam have created different interpretations of the common source of Islam: God and the Prophet Muhammad.

Understanding the origins of Islam and all of its artistic interpretation allows one to start to overcome religious illiteracy. These blog posts – when read together – paint a picture of how to approach dealing with religious illiteracy. They can be divided into two major categories: the problem and the solution. The first three blog posts are designed to represent the problem. By exposing the reader to the cultural tensions that exist between America and Islam, these posts exhibit the problems that can arise from a lack of understanding. The final three blog posts function as the solution: a multifaceted approach to understanding Islam. By juxtaposing the tensions with beautiful Islamic art, these blog posts underline how religious literacy can help solve many problems.

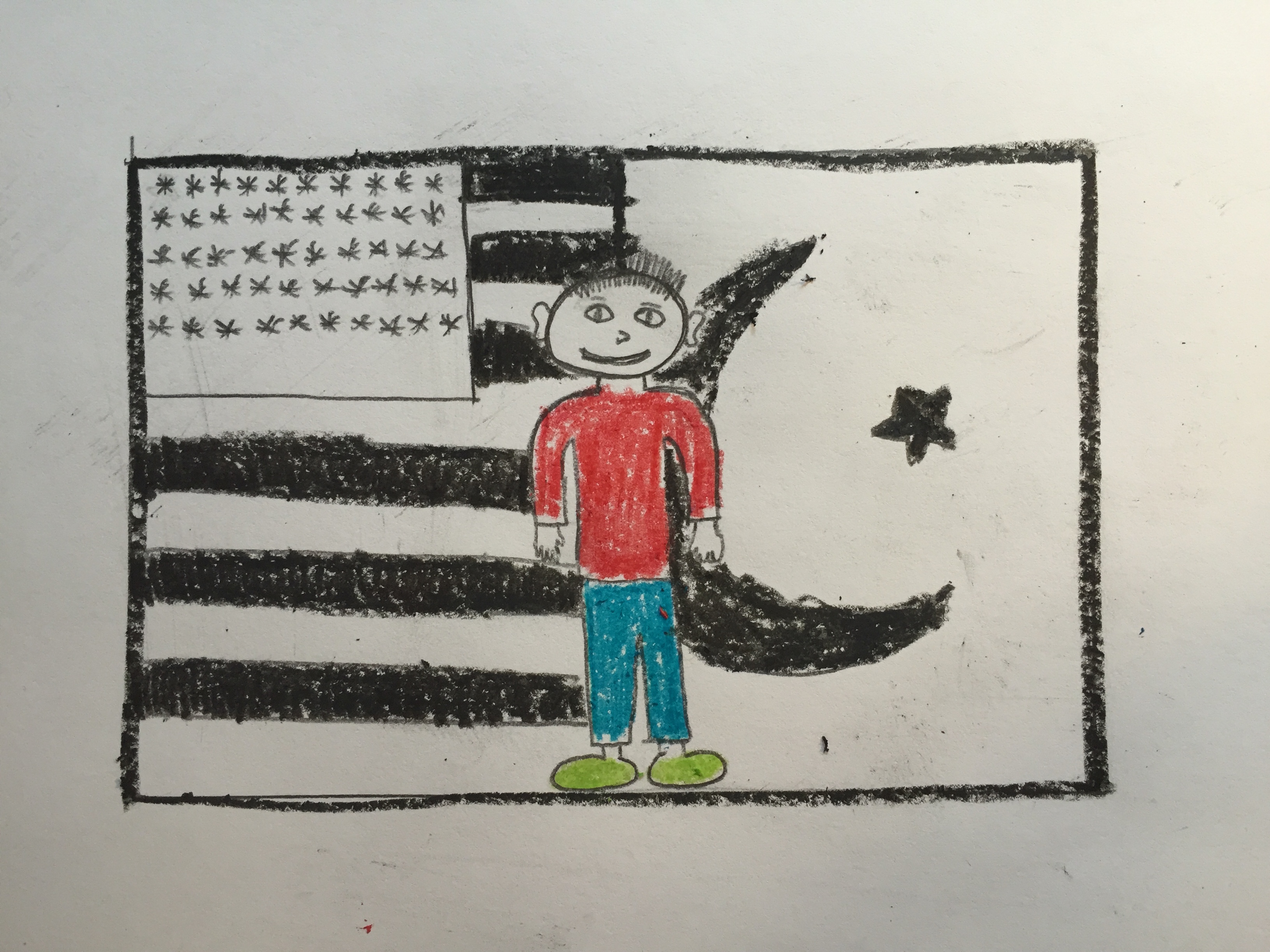

The Problem. The “Westoxification” post references Asani’s point that globalization has caused vast misunderstandings between cultures. This post is designed to not only allow readers to see this conflicting tension, but also to question why they exist and what can be done to ameliorate these problems. The second post, “Conflicting Identities” dives deeper into how these tensions can pose both physical and psychological problems for people stuck between these cultural divides. This post talks about the struggle of a young, successful Muslim immigrant in the United States who feels the hatred of America versus Islam in the wake of the 9/11 attacks. Finally, “Molded Jihad” underlines how one must understand local context in order to understand how some people can interpret the same word in a variety of ways. While some violently interpret jihad, others underline the peaceful internal struggle of jihad. These three posts offer a glimpse into some of the manifestations of conflicting cultures.

The Solution. The final three blog posts highlight specific elements of Islam that help contribute to improve understandings of Islamic teachings and practices. Using art as a medium for expression, these posts help the reader get a sense of the beauty of Islam. “Eating the Qur’an” highlights a specific community in Sudan that physically embody the Qur’an by drinking different verses prescribed by a professional. This post shows how Islam is an incredibly dynamic religion, allowing people to interpret certain teachings in ways that fit their cultural contexts. The next post “Symmetry and Centrality” looks at the connection between Islamic architecture, Islamic designs, and the natural beauty of a flower. By finding similarities and differences between them, one can see how Islamic art underlines an appreciation of the natural beauty surrounding us. Finally, “We are God’s Creations” unifies all Muslims, Jews and Christians by talking about their connection as People of the Book. While there are often disagreements between these religions, it is important to understand that they are all rooted in the same divine teachings.

The take home message from this blog is that expanding one’s knowledge about Islam – not relying on construed Western media outlets – can unify cultures and decrease conflicting tensions. Everyone can relate to artwork. For this reason, using artwork to explain principles in Islam allows for a greater accessibly of its teachings. Islam, just as many other religions, is dynamic. Nebahat Avcioglu’s paper on “Identity-as-Form: The Mosque in the West” underlines this point well: “Islam…is not understood as a static concept, which it often claims to be, but rather as a dynamic process that adapts to specific geographical and cultural conditions” (p. 107). By using a cultural studies approach, one can capture the dynamic nature of Islam and understand why different people interpret Islamic teachings in different ways. With this increased literacy in dealing with difference, perhaps we can dissolve the harmful cross-cultural tensions that intoxicate our modern world. Thanks for taking the time to read my blog, and I hope it helps shed a light on the fascinatingly beautiful religion of Islam!